|

|

|

|

| 1775 | 1776 | 1777 | 1778 | 1779 | 1780 | 1781 | 1782 | 1783... |

|

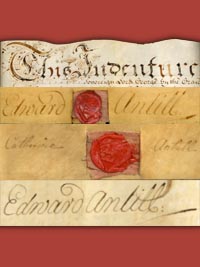

Edward Antill attended Columbia

College, then King's College, graduating in 1762 with an A.M. degree. Having studied law, he was admitted

to the New York bar, but not long after that, he moved to Quebec, marrying Charlotte Riverin in 1767, the

year after he was admitted to the Quebec bar, and

became active in the Masons (search for 'Antill').

Edward's father died in 1770, though a paper on his experiments in wine production was published

in 1771.

Edward Antill and his family were living in Quebec when General Montgomery's forces surrounded the city in December of 1775. Edward had married Charlotte Riverin, the daughter of a merchant, in May of 1767, when she was 15 years old and he was 25. By December of 1775, Charlotte had already had 6 children, 3 of whom had died as infants. Antill was ordered to defend the city but, being an American, he refused and joined Montgomery's forces, being taken on as an engineer. He was then 33 years old. |

| Memoirs of Aaron Burr | December 1775 |

|

Memoirs of Aaron Burr The first plan for the attack upon the British works was essentially different from that which was subsequently carried into execution. Various reasons have been assigned for this change. Judge Marshall says, “that while the general (Montgomery) was making the necessary preparations for the assault, the garrison received intelligence of his intention from a deserter. This circumstance induced him to change the plan of his attack, which had been originally to attempt both the upper and lower towns at the same time. The plan now resolved on was to divide the army into four parts; and while two of them, consisting of Canadians under Major Livingston, and a small party under Major Brown, were to distract the attention of the garrison by making two feints against the upper town of St. Johns and Cape Diamond, the other two, led, the one by Montgomery in person, and the other by Arnold, were to make real attacks on opposite sides of the lower town.” [2] Colonel Burr says, that a change of the plan of attack was produced, in a great measure, through the advice and influence of Mr. Antill, a resident in Canada, who had joined the army; and Mr. Price, a Montreal merchant of property and respectability, who had also come out and united his destiny with the cause of the colonies. Mr. Price, in particular, was strongly impressed with the opinion, that if the American troops could obtain possession of the lower town, the merchants and other wealthy inhabitants would have sufficient influence with the British commander-in-chief to induce him to surrender rather than jeopard the destruction of all their property. It was, as Colonel Burr thought, a most fatal delusion. But it is believed that the opinion was honestly entertained. The first plan of the attack was agreed upon in a council, at which young Burr and his friend, Matthias Ogden, were present. The arrangement was to pass over the highest walls at Cape Diamond. Here there was a bastion. This was at a distance of about half a mile from any succour; but being considered, in some measure, impregnable, the least resistance might be anticipated in that quarter. Subsequent events tended to prove the soundness of this opinion. In pursuance of the second plan, Major Livingston, with a detachment under his command, made a feint upon Cape Diamond; but, for about half an hour, with all the noise and alarm that he and his men could create, he was unable to attract the slightest notice from the enemy, so completely unprepared were they at this point. While the first was the favourite plan of attack, Burr requested General Montgomery to give him the command of a small forlorn hope, which request was granted, and forty men allotted to him. Ladders were prepared, and these men kept in constant drill, until they could ascend them (standing almost perpendicular), with their muskets and accoutrements, with nearly the same facility that they could mount an ordinary staircase. In the success of this plan of attack Burr had entire confidence; but, when it was changed, he entertained strong apprehensions of the result. He was in the habit, every night, of visiting and reconnoitring the ground about Cape Diamond, until he became perfectly familiarized with every inch adjacent to, or in the vicinity of, the intended point of assault. When the attack was about to be commenced, Captain Burr, and other officers near General Montgomery, endeavoured to dissuade him from leading in the advance; remarking that, as commander-in-chief, it was not his place. But all argument was ineffectual and unavailing. The attack was made on the morning of the 31st of December, 1775, before daylight, in the midst of a violent snow-storm. The New-York troops were commanded by General Montgomery, who advanced along the St. Lawrence, by the way of Aunce de Mere, under Cape Diamond. The first barrier to be surmounted was at the Pot Ash. In front of it was a block-house and picket, in charge of some Canadians, who, after making a single fire, fled in confusion. On advancing to force the barrier, an accidental discharge of a piece of artillery from the British battery, when the American front was within forty paces of it, killed General Montgomery, Captain McPherson, one of his aids, Captain Cheeseman, and every other person in front, except Captain Burr and a French guide. General Montgomery was within a few feet of Captain Burr; and Colonel Trumbull, in a superb painting recently executed by him, descriptive of the assault upon Quebec, has drawn the general falling in the arms of his surviving aid-de-camp. Lieutenant Colonel Campbell, being the senior officer on the ground, assumed the command, and ordered a retreat. |

Home |

Suggested Favorite Pages |

Site Map |