The potent influence of the 'Society instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts,

Manufactures and Commerce' in promoting economic diversification in the American colonies has long been recognized,

though probably not adequately appreciated. Illustrative of the stimulus given by the Society to one of the

numerous phases of colonial agriculture which it encouraged is this account of the response of two New Jersey men to the Society's

offer of a premium for the planting of voneyards. One of the men, Edward Antill, received the largest individual

premium ever awarded by the Society to an American. The other, William Alexander, the self-styled Earl of Stirling,

was honoured with a gold medal. Both recipients, and most particularly Antill, were inspired by the Society to make

notable contributions to the history of American viticulture.

Almost from the establishment of the first English settlement in North America there had been efforts to cultivate wine-producing

vineyards. Spurring these endeavors was the hope that both the mother country and colonies might be relieved of their dependence on foreign

sources of wine. Perhaps the earliest attempt to develop a vineyard was made in Virginia in about 1619, with indifferent

results. Subsequently there were many other venture sin grape growing in Virginia, some with strong official encouragement but all

doomed to failure. In South Carolina, French Huguenots, especially skilled in viticulture, made repeated but uniformly unencouraging attempts

to create a wine industry. Indeed similar unpromising experiments were tried in nearly every colony southward of New England.

With rare exceptions attention was centred on the problem of ascertaining which varieties of the European grape

(vitis vinifera) would thrive in the American environment. Native American vines, which grew in profusion throughout the

colonies, were largely ignored.

It was with some awareness of this background of failure that the Society in 1758 offered a premium of 100 pounds to the

colonist who, within seven yeras, should be the first to produce five tuns of red or white wine of acceptable quality.

Presumably it was believed that if encouragement were given to continued experimentation with transplanted varieties of

vitis vinifera, an adaptable variety might ultimately be found. Despite the generous amount of the premium,

which continued to be advertised until 1765, no planters came forward to claim the award.

It was with some awareness of this background of failure that the Society in 1758 offered a premium of 100 pounds to the

colonist who, within seven yeras, should be the first to produce five tuns of red or white wine of acceptable quality.

Presumably it was believed that if encouragement were given to continued experimentation with transplanted varieties of

vitis vinifera, an adaptable variety might ultimately be found. Despite the generous amount of the premium,

which continued to be advertised until 1765, no planters came forward to claim the award.

Undaunted, and still persuaded of the importance of developing a supply of wine within the Empire, the Society renewed its

efforts in a new form in 1762. A premium of 200 pounds was to be granted for the greatest number of vines, not less than

five hundred, which produced 'those Sorts of Wines now consumed in Great Britain.' The vineyard, in order to qualify,

must have been properly planted, fenced, and cultivated between 1st April, 1762 and 1st April, 1767. One such

premium was advertised for the region north of the Delaware River and others for the southern colonies and Bermuda. A second

premium of 50 pounds was to go to the planter of the next greatest quantity of vines, not less than one hundred in number. The terminal

date of the offer was subsequently extended in 1770.

WILLIAM ALEXANDER, LORD STIRLING

Among those who were to compete for the Society's bounty was William Alexander, or, as he was commonly called, Lord Stirling.

Through his gardener, Thomas Burgie, he advised the society in 1767 that he had planted 2100 vines. Earlier, in 1763,

he had explained to his friend, the Earl of Sherburne, the difficulties that confronted an American viticulturist and had

made a plea for governmental encouragement of such projects.

"The making of wine [he wrote on 6th August], also, is worth the attention of Government. Without its aid, the cultivation of the

vine will be very slow; for of all the vines in Europe, we do not yet know which of them will suit this climate; and until that is

ascertained by experiment, our people will not plant vineyards; few of us are able, and a much less number willing, to make the

experiment. I have lately imported about twenty different sorts, and have planted two vineyards, one in this Province

[New York] and one in New Jersey;

but I find the experiments tedious, expensive, and uncertain; for after eight or ten years' cultivation I shall perhaps be obliged

to reject nine tenths of them as unfit for the climate, and then begin new vineyards from the remainder. But, however

tedious, I am determined to go through with it. Yet I could wish to be assisted in it, I would then try to a greater

extent, and would the sooner be able to bring the cultivation of the grape into general use."

It is entirely probably that Stirling was at this time aware of the Society's interest in encouraging the planting of vineyards,

for he had become a member while resident in London in 1760. The son of James Alexander, who had fled from Scotland in 1716

after participating in the Jacobite rising of that time, William was born in New York City in 1726 and inherited a position of wealth

and prominence. After serving briefly in the French and Indian War, he journeyed to England in 1756 and remained there for five years,

during most of which time he was engaged in a fruitless attempt to secure recognition of his claim to the lapsed Earldom of Stirling.

Upon his return to America, he began the development of a considerble estate at Baskingridge, Somerset County, New Jersey,

which soon became his permanent residence. He was appointed a member of the Governor's Council and assumed a leading role in the

political, economic and social llife of New Jersey. With the outbreak of the Revolution, he cast his considerable prestige and ability

on the side of Independence and won distinction as Major-General in the Continental Army.

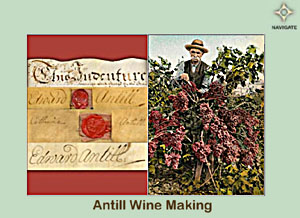

EDWARD ANTILL

Approx. 80 page paper, by Edward Antill

The second claimant of the Society's bounty, Edward Antill, was also one of the leading men in the province. The son of a merchant,

landowner, lawyer and political figure who had emigrated from Richmond, Surrey, prior to 1681, Antill was born in New York City

in 1701. After attaining his majority he settled at Raritan Landing, opposite New Brunswick, in Piscataway Township, New Jersey,

on lands inherited from his father. He married as his second wife a daughter of Governor Lewis Morris, served briefly in the Assembly and for two decades as a member of

the Council, and devoted himself to managing his handsome estate and operating a large brewery.

A persistent advocate of agricultural improvement and a fervent believer in the mercantilist concept of the economic relationship

of the colonies to the mother country, Antill viewed his viticultural project as a patriotic cause. 'When I first

undertook a Vineyard,' he wrote at the end of his life, 'I can without the least spark of vanity say, I did it for the good

of my country, and from a love of mankind...' He explained to the Society that when he learned

premiums were to be offered for various kinds of agricultural prodducts, he gave careful consideration to which of them might be

grown in New Jersey, weighing such factors as soil, topography and climate. He concluded that vineyards were well suited

to his region. It was not the American environment, he maintained, but rather the ignorance and indifference of the American

farmer that waas responsible for the lack of vineyards in the colonies.

"The People of Ameridca are generally unacquainted with the Art of improving & cultivating of Lands to advantage; they jogg on

in the beaten Paths of their Ancestors ... I have been thought by some Gentlemen as well as by Farmers very shimsical in

attempting a Vineyard; it is looked upon as an absurd undertaking, as a farce upon Nature, as though I meant to extort from her

what is not in her power to yield. As if America alone was to be denyed those cheering comforts which Nature with a

bountiful hand Stretches forth to the rest of the World."

ANTILL'S EXPERIMENTS

Having determined upon his course of action, Antill prosecuted the project with remarkable vigour. He began planting in

the spring of 1764, and by the end of 1765 he had a vineyard of eight hundred vines and a flourishing nursery. The

vineyard consisted chiefly of Madeira, Burgundy, and Frontinac grapes, together with a few 'Sweet-water Grape vines,

and of the best

sort of the Native Vines of America by way of tryal.' Planted at a distance of six feet one way and five feet the other,

the vineyard was well managed, cultivated and fenced. Antill deliberately located his vineyard on the south side of a hill

fronting a public road - 'that everyone may see what they otherwise would not believe practicable' - and offered cuttings,

together with proper instructions, to anyone who was interested in emulating his experiment.

sort of the Native Vines of America by way of tryal.' Planted at a distance of six feet one way and five feet the other,

the vineyard was well managed, cultivated and fenced. Antill deliberately located his vineyard on the south side of a hill

fronting a public road - 'that everyone may see what they otherwise would not believe practicable' - and offered cuttings,

together with proper instructions, to anyone who was interested in emulating his experiment.

When the Society's Committee of Colonies and Trade met on 27th October, 1767, it had before it certificates relating to

the vineyards established by Lord Stirling and Edward Antill. It then resolved that Stirling was entitled to the first

premium of 200 pounds and, oddly enough, adopted a similar resolution with respect to Antill. Some weeks later, when the

report of the Committee was made to the meeting of the Society, that part which related to Lord Stirling was disagreed to and the consideration

of the remainder was postponed. At the next meeting of the Society on 2nd December, 1767, it was resolved that Antill should be awarded

the first premium; no mention was made of Lord Stirling. Subsequently, on 24th December, the Society voted to award a gold medal

'to the Rt Honble the Earl of Stirling for having planted 2100 vintes in North America in pursuance of the Views of the Society.'

What the precise nature of the disagreement was between the Committee of Colonies and Trade and the Society is not revealed. Robert Dossie, who was at the time

a member of the Committee, stated that Lord Stirling 'failed in some essential points of certification,' but he does not explain

what these points might have been. The Chairman of the Committee, ehose report had been disagreed to by the Society,

declined to serve any longer in that post, which suggests that the case of Lord Stirling had engendered some ill-feeling. It is

even possible that the Society's action may have been influenced by the fact that William Alexander had chosen to assume a

dignity to which he was not properly entitled and which he had been forbidden to assume by the House of Lords.

Antill was deeply grateful to the Society for both the honourable recognition and the material reward that had been conferred on

him, and he continued to communicate to the Secretary of the Society his enthusiastic plans for furthering the cause of

American viticulture. He had already proposed that the Society should finance a small, model vineyard where

intensive, long-range experiments oculd be carried forward systematically. The cost he extimated at a modest 200 pounds for

seven years. Later, in 1768, he put forth a similar proposal in the New York Gazette, on this occasion appealing to

'the Gentlemen of publick Spirit, in the different colonies, or Bodies of Men associated for promoting Arts, Manufacturers,

and Agriculture' for support. He also reported that he was writing a treatise on viticulture 'collected from the best

Authors, from the Information of the most knowing among the French and Germans, and from many Experiments which I have made

for my own satisfaction.' It was his constant endeavour to stimulate other farmers to plant vineyards. 'I have set it on such a footing

by some Things which I have Published,' he wrote, 'that some People in the Colony of New York & many more in the Colony of

Pennsylvania are become Sanguine in the attempt...'

His zeal for agricultural improvement was not confined to viticulture alone. In the same letter in which he acknowledged

the Society's bounty, he set forth at length 'the best and cheapest method for raising and fattening Hogs, for raising of black

cattle without Milk, for keeping up and increasing the Milk of Cows in Winter, and for stall feeding of Oxen and sheep'. In

In essence, all of these methods involved the use of boiled potatoes as feed. Antill was pleased to communicate this yet Secret

and new discovery to the Honorable Society for the good of the People of England', and in anticipation of 'a premium in some

Degree adequate to the Merit'. In the same letter he also dealt with the medicinal qualities of rhubarb and the suitability

of olive yards to the southern colonies.

Transcending even his interest in agriculture, however, was his patriotic love for his country. 'I read with pleasure,

nay with transport, the proceedings of this most grand and benificent [sic] Society', he exclaimed; 'I see with great Satisfaction

the Arts, Agriculture, and Commerce rising and improving from Every quarter, and a foundation laid for surprising

effects from every Branch and for great increase of wealth and power to the Nation which I pray God to Establish Forever.'

Perhaps Antill's greatest accomplishment and surely his most important contribution to American viticulture was his 'treatise' on the subject. Entitled

'An Essay on the cultivation of the Vine, and the making and preserving of Wine, suited to the different Climates in

North-America', it was published posthumously in 1771 in the first volume of the Transactions of the American Philosophical

Society. In forwarding the piece for publication in May, 1769, Antill wrote 'I have at last, after many hard struggles, and

many a painful hour, labouring under a tedious disorder, finished the essay on the cultivation fo the Vine ...'. He had

recently removed from his estate at Raritan Landing to Shrewbury, New Jersey, where he died on 15th August, 1770.

The first publication by an American on any fruit, Antill's eighty-page essay remained the authorative work on the

subject for more than fifty years. It borrowed heavily from Columella's classical Of Husbandry in Twelve Books, from

Philip Miller's The Gardener's Dictionary, and from other contemporary authorities, but incorporated as well the results

of Antill's own experiments.

THE FAILURE OF TRANSPLANTING FOREIGN VINE STOCK

It was, in one sense, a final monument to failure; to the failure of Antill and all the other colonial viticulturists who had

spent their energies in the futil effort to cultivate vitis vinifera. The European grape could not be grown successfully

in eastern America, where it fell prey to phylloxera, black rot, powdery mildew, and downy mildew. But it was not until half

a century after Antill's death that this fact was at last comprehended and successful efforts were made to domesticate

native American vines and to produce satisfactory hybrids. Antill did not completely ignore the American species.

It was, in one sense, a final monument to failure; to the failure of Antill and all the other colonial viticulturists who had

spent their energies in the futil effort to cultivate vitis vinifera. The European grape could not be grown successfully

in eastern America, where it fell prey to phylloxera, black rot, powdery mildew, and downy mildew. But it was not until half

a century after Antill's death that this fact was at last comprehended and successful efforts were made to domesticate

native American vines and to produce satisfactory hybrids. Antill did not completely ignore the American species.

"The reason for my being silent about Vines that are natives of America is, that I know but little of them, [he wrote

in his 'Essay'] having but just entered upon a trial of them, when my very ill state of health forbad me to proceed.

From what little observation I have been able to make, I look upon them to be more intractable than that of Europe, they

will undergo a hard struggle indeed, before they will submit to a low and humble state, a state of abject slavery ..."

The futility of endeavouring to transplant vitis vinifera to America was at last being recognized. The astute

Robert Dossie was persuaded that the proper course was to develop the native vines, and he was doubtless instrumental

in inducing the Society in 1768 to offer medals for thier cultivation. The anonymous author of American Husbandry,

published in London in 1775, was most insistent that American grapes should be preferred to the European varieties. Antill's work

may be adjudged a failure. But such failures were a necessary prelude to ultimate success. The encouragement that he, and many others,

received from the Society, was instrumental in producing the knowledge that was at last to make possible the effective exploitation

of the American grape.