|

Lewis Morris (October 15, 1671 - May 21, 1746), chief justice of New York and governor of New Jersey, was the first

lord of the manor of Morrisania in New York.

In 1692 he was appointed a judge of the court of common right of East Jersey and was named a member of

Governor Andrew Hamilton's council. He vigorously supported Hamilton, but in 1698 he opposed the appointment of

Governor Jeremiah Basse on the ground that the choice had been made by only ten of the required sixteen proprietors.

His obstructive tactics resulted in his dismissal from the governor's council.

Lewis Morris (October 15, 1671 - May 21, 1746), chief justice of New York and governor of New Jersey, was the first

lord of the manor of Morrisania in New York.

In 1692 he was appointed a judge of the court of common right of East Jersey and was named a member of

Governor Andrew Hamilton's council. He vigorously supported Hamilton, but in 1698 he opposed the appointment of

Governor Jeremiah Basse on the ground that the choice had been made by only ten of the required sixteen proprietors.

His obstructive tactics resulted in his dismissal from the governor's council.

Although Governor Fletcher had issued royal letters patent in May 1697 erecting Morris' New York estate into the

manor of Morrisania, the new lord was less interested in his manorial grant than in the politics of New Jersey.

He went to England in 1702 to promote the transfer of political authority from the Jersey proprietors to the Crown.

Ambitious to be the first royal governor of the province, he was keenly disappointed when the ministry named

Lord Cornbury to be governor of both New York and New Jersey. As a member of Cornbury's council for New Jersey,

Morris became an outspoken opponent of that unscrupulous official. Dismissed from the council, he was elected

in 1707 to the assembly, where he collaborated with Samuel Jennings in formulating the protest to Queen Anne

against Cornbury's reprehensible conduct, which was largely responsible for the governor's removal from office.

After 1710, Morris supported the admirable administration of his friend Robert Hunter. He spent more time in

New York, especially after Hunter appointed him chief justice of the supreme court of that province (1715).

He continued, however, to serve upon the govenor's council for New Jersey under Burnet andd Montgomerie. With

the administration of Governor William Cosby the lord of Morrisania found himself once more at odds with the

representative of the Crown. When Cosby sought to establish a court of chancery to hear his suit against

Rip Van Dam, chief-justtice Morris pronounced the whole proceeding illegal, whereupon the governor removed

him and appointed James De Lancey, 1703-1760, in his place (August 21, 1733). Morris was elected to the

assembly from the town of Eastchester, and joined James Alexander and William Smith in championing the

popular cause against the "court party" led by Cosby and De Lancey. In 1734 he presented the assembly's

grievances in London, where he failed to secure the removal of Governor Cosby but won a vindication of

his own conduct as chief justice.

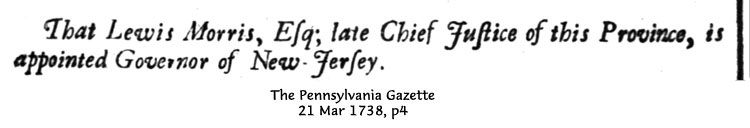

When the political connection between New York and New Jersey was severed, he became governor of the latter

province (1738). Though he had challenged the royal prerogative as represented by Cornbury and Cosby, he

permitted no questioning of his own authority. He frequently lectured the provincial assembly on its duties

and complained to the lords of trade in 1740 that the legislators "fancy themselves to have as much power

as a British House of commons, and more" ("Papers of Governor Lewis Morris," post, p.23). His administration

was marked by bitter and wordy quarrels with the assembly over taxation, support of the militia, issuance of

bills of credit, and validity of land titles.

For many years Lewis Morris was an active churchman, serving from 1697 to 1700 as a vestryman of Trinity Church

and encouraging the Society for the Propogation of the Gospel in its missionary enterprises. In 1702 he

suggested to the Society that New York, as the center of English America, was a proper place for a college

and that Queen Anne might be persuaded to grant her farm in New York toward the project. Morris' public

career was never touched by the least suspicion of political jobbery. His enemies accused him of inordinate

vanity, and no doubt he was fully conscious of his talents, which were great. The contentious spirit,

manifest in his youth, grew stronger with the passing years and involved him in controversy until his death,

which occured at "Kingsbury" near Trenton. He was buried at Morrisania with simple rites in accordance with

the terms of his will. The bulk of his estate was divided between his son Lewis, who became second lord of

the manor and his son Robert Hunter Morris, who inherited the New Jersey property.

("The Papers of Lewis Morris, Governor of the Province of New Jersey," NJ Hist. Soc. Colls., vol. IV (1852);

Robert Bolton, A Hist. of the County of Westchester (2 volumes, 1848); William Smith, The Hist. of the Late

Province of NY (1829); Archives of the State of NJ, i ser. IV-VII (1882-83); EB O'Callaghan, Docs. Rel. to

the Col. Hist.)

|

The early education of Lewis was respectable. At the age of sixteen he was fitted for college, and was entered at Yale college, the honors of which he

received in due course, having acquired the reputation of good scholarship, and a strict morality. Immediately on leaving college, he returned to his father's

residence, where he devoted himself to the pursuits of agriculture. As he entered upon manhood, he seems to have possessed every thing which naturally

commands the respect, and attracts the admiration of men. His person was of lofty stature, and of fine proportions, imparting to his presence an

uncommon dignity, softened, however, by a disposition unusually generous and benevolent, and by a demeanor so graceful, that few could fail to do him

homage.

Although thus apparently fitted for the enjoyment of society, Mr. Morris found his greatest pleasure in the endearments of domestic life, and in attention to

his agricultural operations. He was early married to a Miss Walton, a lady of fortune and accomplishments, by whom he had a large family of six sons and

four daughters.

The condition of Mr. Morris, at the time the troubles of the colonies began, was singularly felicitous. His fortune was ample; his pursuits in life consonant to

his taste; his family and connections eminently respectable, and eminently prosperous. No change was, therefore, likely to occur which would improve his

condition, or add to the happiness which he enjoyed. On the contrary, every collision between the royal government and the colonies, was likely to

abridge some of his privileges, and might even strip his family of all their domestic comforts, should he participate in the struggle which was likely to ensue.

These considerations, no doubt, had their influence at times upon the mind of Mr. Morris. He possessed, however, too great a share of patriotism, to surer

private fortune, or individual happiness, to come in competition with the interests of his country. He could neither feel indifferent on a subject of so much

magnitude, nor could he pursue a course of neutrality. He entered, therefore, with zeal into the growing controversy; he hesitated not to pronounce the

measures of the British ministry unconstitutional and tyrannical, and beyond peaceful endurance. As the political condition of the country became more

gloomy, and the prospect of a resort to arms increased, his patriotic feeling appeared to gather strength; and although he was desirous that the controversy

should be settled without bloodshed, yet he preferred the latter alternative, to the surrender of those rights which the God of nature had given to the

American people. About this time, the celebrated congress of 1774 assembled at New York. Of this congress Mr. Morris was not a member. He

possessed a spirit too bold and independent, to act with the prudence which the situation of the country seemed to require. The object of this congress

was not war, but peace. That object, however, it is well known, failed, notwithstanding that an universal desire pervaded the country, that a compromise

might be effected between the colonies and the British government, and was made known to the latter, by a dignified address, both to the king and to the

people of Great Britain.

In the spring of 1775, it was no longer doubtful that a resort must be had to arms. Indeed, the battle of Lexington had opened the war; Shortly after which

the New York convention of deputies were assembled to appoint delegates to the general congress. Men of a zealous, bold, and independent stamp,

appeared now to be required. It was not singular, therefore, that Mr. Morris should have been elected.

On the 15th of May, he took his seat in that body, and eminently contributed, by his indefatigable zeal, to promote the interests of the country. He was

placed on a committee of which Washington was the chairman, to devise ways and means to supply the colonies with ammunition and military stores, of

which they were nearly destitute. The labors of this committee were exceedingly arduous.

During this session of congress, Mr. Morris was appointed to this delicate and difficult task of detaching the western Indians from a coalition with the

British government, and securing their cooperation with the American colonies. Soon after his appointment to this duty, he repaired to Pittsburgh, in which

place, and the vicinity, he continued for some time zealously engaged in accomplishing the object of his mission. In the beginning of the year 1776, he

resumed his seat in congress, and was a member of several committees, which were appointed to purchase muskets and bayonets, and to encourage the

manufacture of salt-peter and gunpowder.

During the winter of 1775 and 1776, the subject of a Declaration of Independence began to occupy the thoughts of many in all parts of the country. Such

a declaration seemed manifestly desirable to the leading patriots of the day, but an unwillingness prevailed extensively in the country, to destroy all

connection with Great Britain. In none of the colonies was this unwillingness more apparent than in New York.

The reason which has been assigned for this strong reluctance in that colony, was the peculiar intimacy which existed between the people of the city and

the officers of the royal government. The military officers, in particular, had rendered themselves very acceptable to the citizens, by their urbanity; and had

even formed connections with some of the most respectable families.

This intercourse continued even after the commencement of hostilities, and occasioned the reluctance which existed in that colony to separate from the

mother country. Even as late as the middle of March, 1776, Governor Tryon, although he had been forced to retreat on board a British armed vessel in

the harbor for safety, bad great influence over the citizens, by means of artful and insinuating addresses, which he caused to be published and spread

through the city. The following extract from one of these addresses, will convey to the reader some idea of the art employed by this minister of the crown,

to prevent the people of that colony from mingling in the struggle.

"It is in the clemency and authority of Great Britain only that we can look for happiness, peace, and protection; and I have it in command from the king, to

encourage, by every means in my power, the expectations in his majesty's well disposed subjects in this government, of every assistance and protection the

state of Great Britain will enable his majesty to afford them, and to crush every appearance of a disposition, on their part, to withstand the tyranny and

misrule, which accompany the acts of those who have but too well, hitherto, succeeded in the total subversion of legal government. Under such

assurances, therefore, I exhort all the friends to good order, and our justly admired constitution, still to preserve that constancy of mind which is inherent in

the breasts of virtuous and loyal citizens, and, I trust, a very few months will relieve them from their present oppressed, injured, and insulted condition.

"I have the satisfaction to inform you, that a door is still open to such honest, but deluded people, as will avail themselves of the justice and benevolence,

which the supreme legislature has held out to them, of being restored to the king's grace and peace; and that proper steps have been taken for passing a

commission for that purpose, under the great seal of Great Britain, in conformity to a provision in a late act of parliament, the commissioners thereby to be

appointed having. also, power to inquire into the state and condition of the colonies for effecting a restoration of the public tranquillity."

To prevent an intercourse between the citizens and the fleet, so injurious to the patriotic cause, timely measures were adopted by the committee of safety;

but for a long time no efforts were availing, and even after General Washington had established his headquarters at New York, he was obliged to issue his

proclamation, interdicting all intercourse and correspondence with the ships of war and other vessels belonging to the king of Great Britain.

But, notwithstanding this prevalent aversion to a separation from Great Britain, there were many in the colony who believed that a declaration of

independence was not only a point of political expediency, but a matter of paramount duty. Of this latter class, Mr. Morris was one; and, in giving his vote

for that declaration, he exhibited a patriotism and disinterestedness which few had it in their power to display. He was at this time in possession of an

extensive domain, within a few miles of the city of New York. A British army had already landed from their ships, which lay within cannon shot of the

dwelling of his family. A signature to the Declaration of Independence would insure the devastation of the former, and the destruction of the latter. But,

upon the ruin of his individual property, he could look with comparative indifference, while he knew that his honor was untarnished, and the interests of his

country were safe. He voted, therefore, for a separation from the mother country, in the spirit of a man of honor, and of enlarged benevolence.

It happened as was anticipated. The hostile army soon spread desolation over the beautiful and fertile manor of Morrisania. His tract of woodland of more

than a thousand acres in extent, and, from its proximity to the city, of incalculable value, was destroyed; his house was greatly injured; his fences ruined; his

stock driven away; and his family obliged to live in a state of exile. Few men during the revolution were called to make greater sacrifices than Mr. Morris;

none made them more cheerfully. It made some amends for his losses and sacrifices, that the colony of New York, which had been backward in agreeing

to a Declaration of Independence, unanimously concurred in that measure by her convention, when it was learned that congress had taken that step.

It imparts pleasure to record, that the three eldest sons of Mr. Morris followed the noble example of their father, and gave their personal services to their

country, during the revolutionary struggle. One served for a time as aid-de-camp to General Sullivan, but afterwards entered the family of General Greene,

and was with that officer during his brilliant campaign in the Carolinas; the second son was appointed aid-de-camp to General Charles Lee, and was

present at the gallant defense of Fort Moultrie, where he greatly distinguished himself. The youngest of these sons, though but a youth, entered the army as

a lieutenant of artillery, and honorably served during the war.

Mr. Morris left congress in 1777, at which time, he received, together with his colleagues, the thanks of the provincial convention, "for their long and

faithful services rendered to the colony of New York, and the said state."

In subsequent years, Mr. Morris Served his state in various ways. He was often a member of the state legislature, and rose to the rank of major general of

the militia.

The latter years of Mr. Morris were passed at his favorite residence at Morrisania, where he devoted himself to the noiseless, but happy pursuit of

agriculture; a kind of life to which he was much attached, and which was an appropriate mode of closing a long life, devoted to the cause of his country.

He died on his paternal estate at Morrisania, in the bosom of his family, January, 1798, at the good old age of seventy-one years.

|