|

The Davis Branch

UPDATED 10 May 2016 |

|

| |

|

During a dramatic escape from beleaguered Harpers Ferry, Benjamin F. "Grimes" Davis was able to capitalize on his Southern accent to capture James Longstreet's reserve ammunition train. The Alabama-born West Pointer (1854) and wounded veteran of Indian fighting in the infantry and dragoons along the Gila River in New Mexico, had remained loyal to the Union. His Civil War-period assignments included:

Briefly serving in the California volunteers, he resigned that commission when his regular army regiment was ordered to the East. He fought in the siege of Yorktown and at Williamsburg before being assigned to command a New York regiment in the early summer of 1862. Serving in the vicinity of Harpers Ferry, the regiment was entrapped at that place during the Antietam Campaign. Davis urged upon his commander that all the cavalry at the doomed post be allowed to cut their way out. It was reluctantly agreed to and the attempt was made on the night of September 14, 1862. After a series of minor collisions with Confederate pickets, the 8th managed to stumble upon the enemy wagons and Davis was able, the darkness concealing the color of his uniform, to order the train into his column. Many of the teamsters did not know they were prisoners until daylight. He was brevetted for his action.

Joining the Army of the Potomac, Davis commanded a brigade at Antietam and his regiment at Fredericksburg.

During the Chancellorsville Campaign he took part in Stoneman's Raid. The next month he was killed,

commanding a brigade, in the great cavalry battle at Brandy Station.

| |

|

| |

|

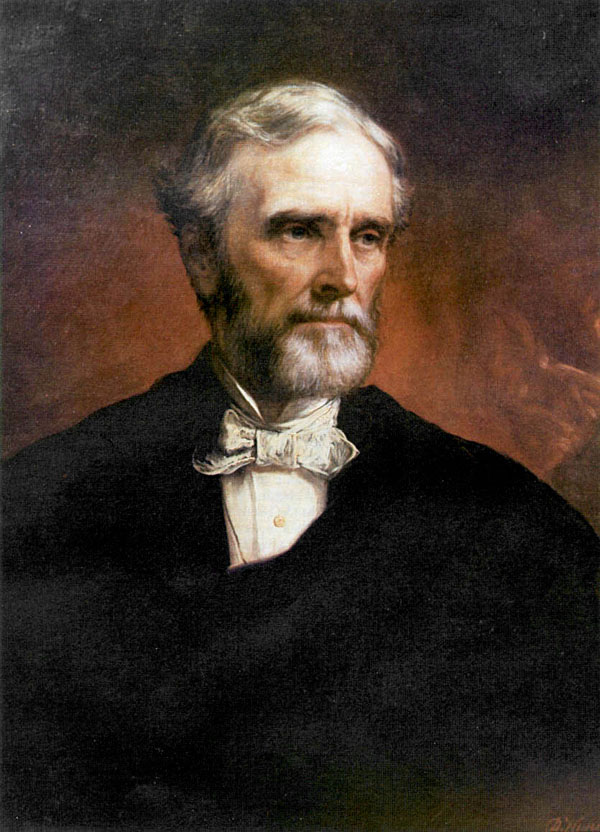

The only president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis proved to be something less than the revolutionary leader necessary to lead a fledgling nation to independence; he himself would have preferred to serve as a military leader. Born in Kentucky, he was graduated from West Point in 1828 and was posted to the Pacific Northwest. There he served with the infantry until 1833 when he transferred to the dragoons. Two years later he resigned as a first lieutenant when he eloped with the daughter of his commander, Zachary Taylor. Thereafter a Mississippi planter, he lost his wife shortly after the wedding and then married Varina Howell. Elected as a Democrat to Congress he served in the house of Representatives from 1845 to 1847. During the Mexican War he compiled an enviable record as colonel of the 1st Mississippi Rifles. Wounded at Buena Vista, he turned down a commission as a brigadier general. He then won a seat in the U.S. Senate, which he held until named Franklin Pierce's war secretary in 1853. He held this post for the full tenure of the Pierce presidency and then won reelection to the Senate. A staunch supporter of states' rights, he backed his state's secession and made a powerful speech on the floor of the Senate when he and four other senators withdrew from that body on January 21, 1861. Almost immediately named commander of the state military forces with the rank of major general -- in recognition of his Mexican War service -- he became a compromise candidate for the provisional presidency of the Confederacy and was so elected on February 9, 1861. Inaugurated nine days later in Montgomery, Alabama, he was elected as regular president for a six-year term on November 6, 1861, and was reinauguared on Washington's Birthday in Richmond. His interest in the military defense of his country soon became apparent; his early war secretaries served as little more than clerks as he himself supervised the affairs of the department. He made frequent forays into the field, arriving at 1st Bull Run just as the fight was ending, and was later under fire at Seven Pines where he placed Robert E. Lee in command of what became the Army of Northern Virginia. Later he toured the western theater where he supported his old friend Braxton Bragg agaionst the criticisms of his subordinates. His handling of the high command was extremely controversial. There were long-standing feuds with Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston. His defense of certain non-performing generals, such as Bragg and Pemberton, irritated many in the South. On the political front his autocratic ways fostered a large and well-organized anti-Davis faction in the Confederate Congress, especially in the Senate. His attempts to manage the war effectively by placing more power in the hands of the central government were often thwarted by the states' rights philosophy that had led to its very founding. It is quite apparent that he is more popular in the South today than he was during his tenure. Upon the fall of Richmond he fled south with the remnants of his governmenbt and was finally captured near Irwinville, Georgia, on May 10, 1865. He was sent off to prison at Fort Monroe, faced with charges of treason. Never brought to trial, he was finally released on bail after two years of confinement.

Always contentious, he wrote his autobiography entitled The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

In this 1881 work he refought the war, including his views of those feuds with officers

like Beauregard and Johnston who received much of the blame for the Confederacy's demise.

He lived out his remaining years in Mississippi, never seeking to have his citizenship restored.

In spite of this, it was restored during the presidency of Jimmy Carter.

|

Copyright © 1997, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 1997, Mary S. Van Deusen