Pilot Lewis Sticks by His Ship Even After Heroic Efforts the Craft An Aerial Limousine

CHAPTERS on chapters have been added to the imperishable records of the flying men and field personnel of the States air mail

during the past days of January, 1912, unwritten stories of the achievements of the drivers of the world famous silver winged ships

that have been builded and and cared for by the "Motor Macks" of the Reno field and their co-workers at the San Francisco terminal

of the Transcontinental Red Line air road.

During the month of January, 1923, records have been smashed to smithereens. Ships have withstood tests of the elements

that have obtained no place else on earth.

January 27, 1923, was a day of cyclonic gales that came out of the West and North over the dreaded "Hump."

It will long live in the memories of the hundreds of residents that watched, with bated breath, the combat of Pilot [Burr H.] Winslow

with tho hurricane over Verdi, twelve miles west of Reno, and over the city itself.

The story of Pilot [Claire K.] Vance upon this same day coming from San Francisco to Reno is a raising story of the downright bravery of these aces

of the air mail service.

Buffeted about after he had almost made the "Hump." he then had a fight for life to keep a level keel, was driven back to Sacramento

by a force of wind that was mere minutes of time covering the distance back to a landing.

Then came the rustling of the mail to a limited train and then the record flight back to the silver birds cote on the bay.

Earlier in the month the dense and snow storm over the Sierra blew and tossed Vance and [Harry W.] Huking off course. Lost - darkness - wandering through the night - tramping distances in circles

until friendly daylight dissipated the white mists.

Then again the breaking of the flight record with 370 pounds of mail by Huking, making the time from San Francisco to Reno in one minute less than

the [xx] of one hour and nineteen minutes made by that premier flyer, Boggs.

There is the unwritten story of [Harold T.] "Slim" Lewis, overseas ace-driver of the official limousine - the only ship of its type in the United States and only one other in existence

and that's over in England, an Official D II 4-B.

There is no end to the thrilling, intense stories of the flying men, and their [xx] records of the sensational experiences of these Americans would fill volumes.

One has to dig and dig for the facts - they are a close mouth lot of men: all are doers. Men connected with this service will find that every man is from Missouri.

Late August of last year Second Assistant Postmaster General Paul Henderson was visiting in San Francisco on official business. His air limousine was despatched

from Chicago to San Francisco under the piloting of that incomparable six foot, two inch perfect physical speciman, "Slim" Lewis.

He followed the mail ships as they hopped their divisions.

He was not agreeably impressed with the looks of the hundreds of miles of silent places along the Red Line road between Salt Lake and San Francisco, and he said so.

These boys all speak their minds, whether in their few words of description of deadly danger experienced in their longer dissertations of an ill-fitting flying suit,

or a missing motor. They speak right out.

Lewis returned to Reno November 1, 1922, from San Francisco, following Vance in.

Mr. Henderson had probably heard a good many tales of the dangers of the "Hump" and that terrible hundred miles of terrain where the silver ships could not land without

a 'washout.'

In any event he was said to have received summons to repair to Washington, and he did via a railroad Pullman.

Superintendant Nelson, of the Rock Springs - San Francisco division, returned with Lewis to Reno.

They arrived too late to make the hop to Elko and Salt Lake and remained overnight in Reno.

It was late in the afternoon of November 2d, when Lewis took off at Reno field with Superintendent Nelson.

Nelson was seated comfortably in the easy chair of the limousine smoking a cigar, hat off and on top of the world, so to speak - pretty soon he was!

Lewis circled about the hangar and with half of his magnificent body showing above the cockpit waved a gauntleted glove in a good-bye to the crowd

that so interestedly watched his beautiful handling of the $25,000 ship.

There was a storm coming from the west. Black clouds were piling up and [xx] down from the saw tooth peaks of the high Sierras.

The palace ship was off like the wind, showing a speed seldom ever exhibited at this field.

High, higher, the ghost-lighted ship gained speed. Through the twin nipples of the ruged mouth of Truckee canon to the east,

he soon appeared a wee speck.

The dark clouds from the west soon enveloped the basin of the Truckee.

Then the speeding storm mists blotted out the entire sky. The last seen of the official plane

was under the edge of the fast moving storm.

Four o'clock was the time that was scheduled for Lewis to make Elko.

Nothing was heard of the pilot and passenger until 8:30 p.m., when Major Tomlinson, of Reno field received a flash that the prize ship of the service had crashed, fourteen miles west of Battle Mountain, Nevada.

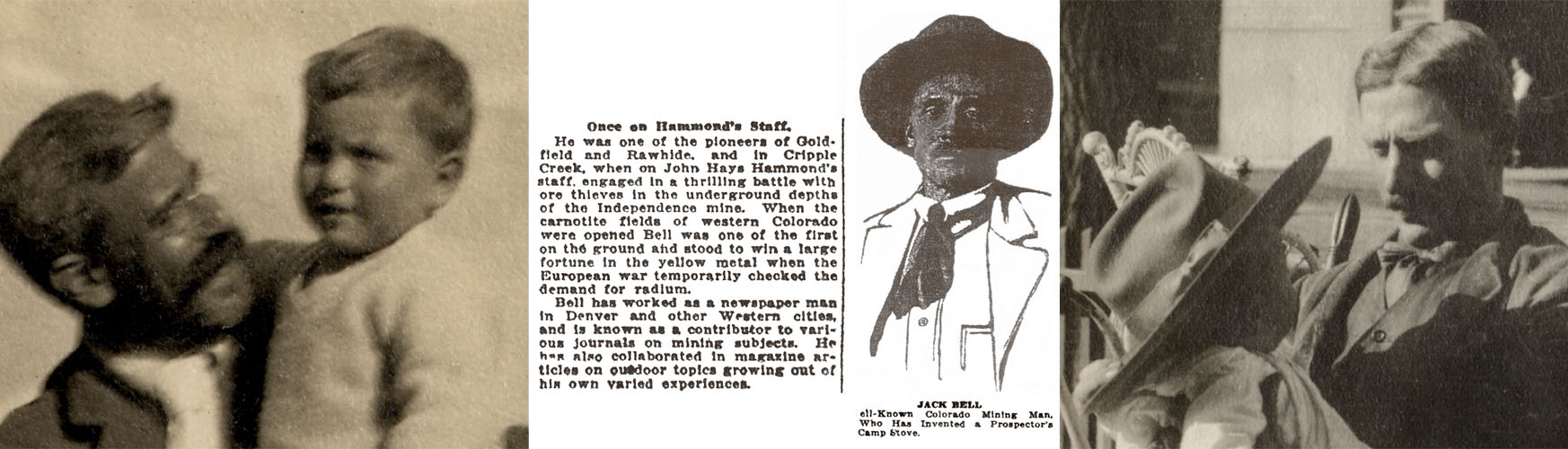

It was not until 11 o'clock that a message was received at Reno field giving part of the details of the accident. The report said Lewis had forced a landing along the

highway running paralllel with the Southern Pacific railway.

Repairs were ordered, consisting of two wings, propellor and some minor parts.

No one was hurt or even much shaken.

She had run off the highway and nosed into a ditch - at 6 p.m., in a storm and in dense darkness - a feat by Lewis that speaks for itself.

Tomlinson called Chief Mechanic Frank Caldwell. The Chief, in turn, routed out Ralph M. Case and Earl W. Bigard, top mechanics.

There was a high wind, snow and the thermometer going down all the time. These three men drove out to the hangar, a distance of two miles and a half from the Reno postoffice.

They assembled the wings and other repair material and reached the union depot in time to load the silvered wings on train number 22, a fast mail train.

Case and Bigard accompanied the load, with their tool kits. The cold increased as the train sped eastward. They arrived at the wreck

at 6:30 a. m., November 3.

The wind was blowing a gale. The snow was piling ujp.

Lewis, with a staunchness and nerve of his breed of flying man was beside the great broken winged bird that was his pride.

It would be hard just exactly to explain the feeling of a pilot who loved his ship, unless one takes the parallel of having a costly favorite automobile

or gun, smashed, or a woman who had torn and burned her favorite new gown, on the eve of some function.

The tail of the ship stood almost straight up into the air. It looked for all the world like a descent from the altitudes, and a nose dive [xx]

bonfire going. These "Motor Macks" got busy, right off the reel.

The ship was repaired and tuned up by these experts and was ready for flight. However, the work of heating irons

and applying the motor for oil pressure consumed almost the entire afternoon.

Lewis was working like a trojan with the mechanics. When repairs were made he debouched across the snow-covered

fields for a distance of four miles and begged and borrowed a Fresno scraper and with a team hauled and tugged his implement of road building to the plane.

For the entire afternoon he scraped a runway for his take-off.

It was almost dark when he made the run and took off into the air.

The observers were one voice in stating that Lewis in making his get-a-way on the short narrow runway accomplished what seemed absolutely impossible.

Telegraph poles close along one side, and the narrow wheel base, with deep ditches on both sides made the thrilling sight an epic in the game of flying.

Away he tore, landing at Battle Mountain in the darkness, without mayhap.

The "Motor Macks," like Lewis, had been without food for all that time.

Their one idea was to carry on.

This is but one of the many incidents that are of dry report to be found in the official records of

the United States air mail fields.

Lewis tore into Salt Lake the next morning and away he flew into his hangar at the Chicago field.

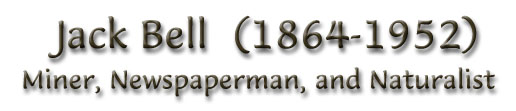

The official [xx] is an aircraft that has but one likeness. By many it is said that this palace of the air has no counterpart,

except on general lines of construction.

The ship is done in red and gold.

The enclosed limousine is under the wings, where are located the mail pits on the regular ships.

There is fifty cubic feet of space. There are rounded metal enforced air tight windows, the material

[xx] windows being composition that is not affected by wind or change of atmosphere.

The revolving, green plush easy chairs, facing each other with plenty of room for stretching out one's legs, make a cozy, comfortable nest.

There is a folding table that can be placed between the chairs.

An entire smoking outfit rests at convenient hand.

There are vases for flowers placed upon the wainscoating on the beautiful and tasteful interior.

Playing cards are in a rack, cuspidors on the floor.

Instruments are inset to read the ship's doings.

Ready installation of radio telephone is arranged, for the coming of this wonderful device.

There are methods to regulate the temperature of the room.

In all, it is the peak of craftsmanship and construction - the very last word in luxury of air travel.

A passenger can sit with high-power glasses, without one bit of inconvenience, and with but the muffled roar of the

motor have conversation.

The noise no more [xx] than the [xx] of a high-powered automobile.

All of the interesting panorama below, and yes, above, the flight of the water fowl, and the eagle family, and the ever-changing

cloud effects and coloring - all are there. Then down on the terrain the pictures of the great open uninhabited places can be viewed in

every comfort, and the vastness of the illimitable spaces can be vis[xx].

The threads that appear to wind in and out among the little dots that are the mountain ranges down, down far below are the transcontinental

limited railway highways. When one leaves Reno and flies to Salt Lake with the every comfort of the air limousine,

the mind is clear and unhampered with the attendant worries of the wind that cuts like a knife if any part of the bodey is exposed to the

friction of the hurricane speed of the ship. Travelling thus with every known device for safely at hand, with pilots like Lewis and the men

that fly the "Hump," or with Blanchfield at the helm - the element of danger is almost zero - and one feels no desire to speculate on

crackups, crashes and washouts.

The names of Winslow, Vance, Huking and Blanchfield are of a surety to be houseworld words. Already the children, when they hear the growl of

a Liberty motor far up in the sky, are speculating upon the name of the pilot and of the number of the ship and the possible destination of the mail craft.

The novelty to the children does not wear away and becomes a thing of such ordinary occurrence that a ship can take over the city at 3,000 feet above them without [xx]

the youngster is interested deeply in the great silver winged speedsters that flash across the sky with such lightning speed.

They talk about the ships, they have all sorts of string-propelled toy planes, they have them numbered just like the wonderful ether birds of Uncle Sam.

It is amazing, the interest and knowledge that the children of Reno have for this means of transportation.

On the afternoon of January 17, 1923, Pilot Harry W. Huking left the San Francisco field for Reno on regular schedule time, about 2 p. m.

He took off through a ground fog that had no visibility and no ceiling.

He knew from the weather reports that the fog only obtained over the reaches of the coast line.

He took his ship up into the air at a dangerous angle, and zoomed and zoomed, and then, getting his direction like the birds of the air, he started for Reno.

There was a gale at his tail.

He kept his plane up in the sky at 14,000 feet altitude. He was making a record and he knew it.

"When I realized that I had passed over Sacramento in better than record time, I knew that I would come near breaking the record made by Boggs with his light ship.

I stepped on her. Not [xx] foolhardly - but I stepped the revolutions up to a bit better than 1500 per minute.

When I looked at my clock and saw that I had just reached Donner Lake - that's just a step over the 'Hump' - in a bit less than an hour I knew that I

was certainly traveling at a speed far grater than I had ever before attained in any flight, for distance.

"I struck the horrors of the [xx] miles from Reno, in the wink of an eye.

In all my life I never experienced just bump after bump - Gee Christmas! I thought that the ship would disintegrate into a thousand pieces.

The forces of the air butts were so tremendous that I thought that my [xx] would never stand the strain.

It was the worst experience I have ever had, and believe me I never ant another like it.

"Then I noticed that I had lost altitude in incalcuable time. I was down from 14,000 to 8000 and headed for Reno field like the mill tails of hades.

I crossed over the field at this same heiht - 8000 feet.

I was afraid to nose her down with the terrific speed, with the hurricane batting at my tail.

I circled the field twice, but looking at the time I was amazed to see that I had covered the distance from San Francisco in just one hour and seven minutes.

I nosed her down after a couple of circles and when the wheels touched my record of one hour and eighteen minutes was official made."

This great record was made with plane No. 167 and carrying a load of mail that weighed 370 pounds.

The distance that is called for in direct triangulation, according to the gtovernment measurements, is 195 miles. At no time has a pilot

negotiated the run from the coast to Reno within that prescribed distance.

The amount of and [xx] from the number of revolutions, can be accurately reckoned, taking the time the motor is burning gas at hours and minutes flying time.

The service crews at the field figure these distances traveled by the ships within a fraction of certainty.

As a matter of fact they are the only ones in the service who have any idea of distances covered by the ships of the air mail.

They don't make a record of these distances - it is not required.

When something unusual happens they measure the gas that is retained in the tank and make their calculations.

The distance reckoned by them as actually flown by Huking, in and out, up and down, on this trip was within a fraction of 230 miles, and that distance was covered

in the remarkable time of one hour and seven minutes.

However, that record cannot stand.

All record official must be made from the time the wheels leave the ground until they again touch terri firma at destination.

On Janaury 12, 1923, all existing speed records in regular flight from San Francisco to Rock Springs, Wyoming, with the mail were knocked

galley west by these wondermen of the air mail.

The actual flying time for the distance of (Red Line measure) 786 miles was covered in the remarkable time of five hours and fifty-eight minutes, as given in the official

log of Superintendent Nelson [xx] division.

Pilot Winslow covered the distance from San Francisco to Reno in one hour and thirty-six minutes, tieing the phenominal speed made by [Claire K.] Vance a year ago.

Pilot [Harold T.] Lewis took the mail at Elko and hurried through the air lane along the Red Line road [xx] one hour and thirty-five minutes.

Bonstra was holding his whirring ship in leash and away he went over the high tops at 12,000, heading for Rock Springs, Wyoming, making the run

in the wonderful time of one hour and seventeen minutes.

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell.)

(The thrilling, never-before-heard-of experiences of Pilot Winslow stationary over Reno for almost a half hour at a time

his battle up there in full view of the hundreds, the appeals of citizenry to the field manager to tell them what the trouble was that

held the great ship stationary a mile above them, will be part of the narrative of Jack Bell in the next copyright article.)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen