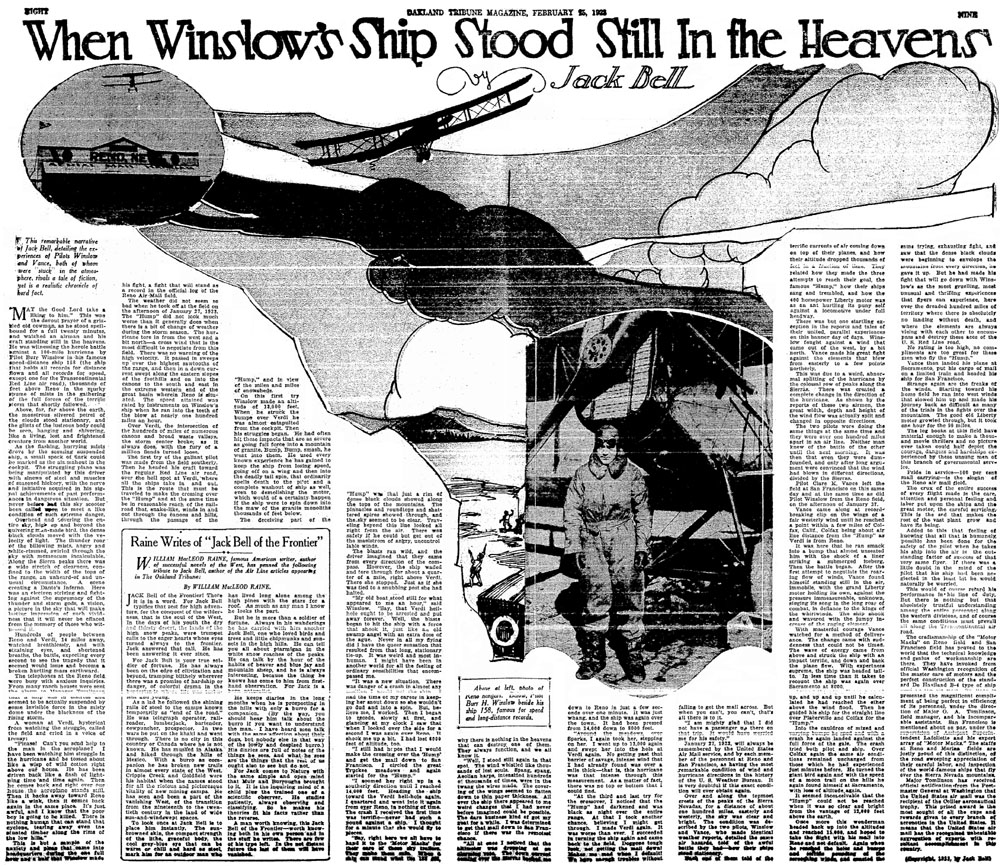

This remarkable narrative of Jack Bell, detailing the experiences of Pilots Winslow and Vance, both of whom were "stuck" in the atmosphere,

rivals a tale of fiction, yet is a realistic chronicle of hard fact.

"May the Good Lord take a liking to him."

This was the devout prayer of a grizzled old cowman, as he stood spellbound for a full twenty minutes, and watched an airman and his craft standing still in the heavens.

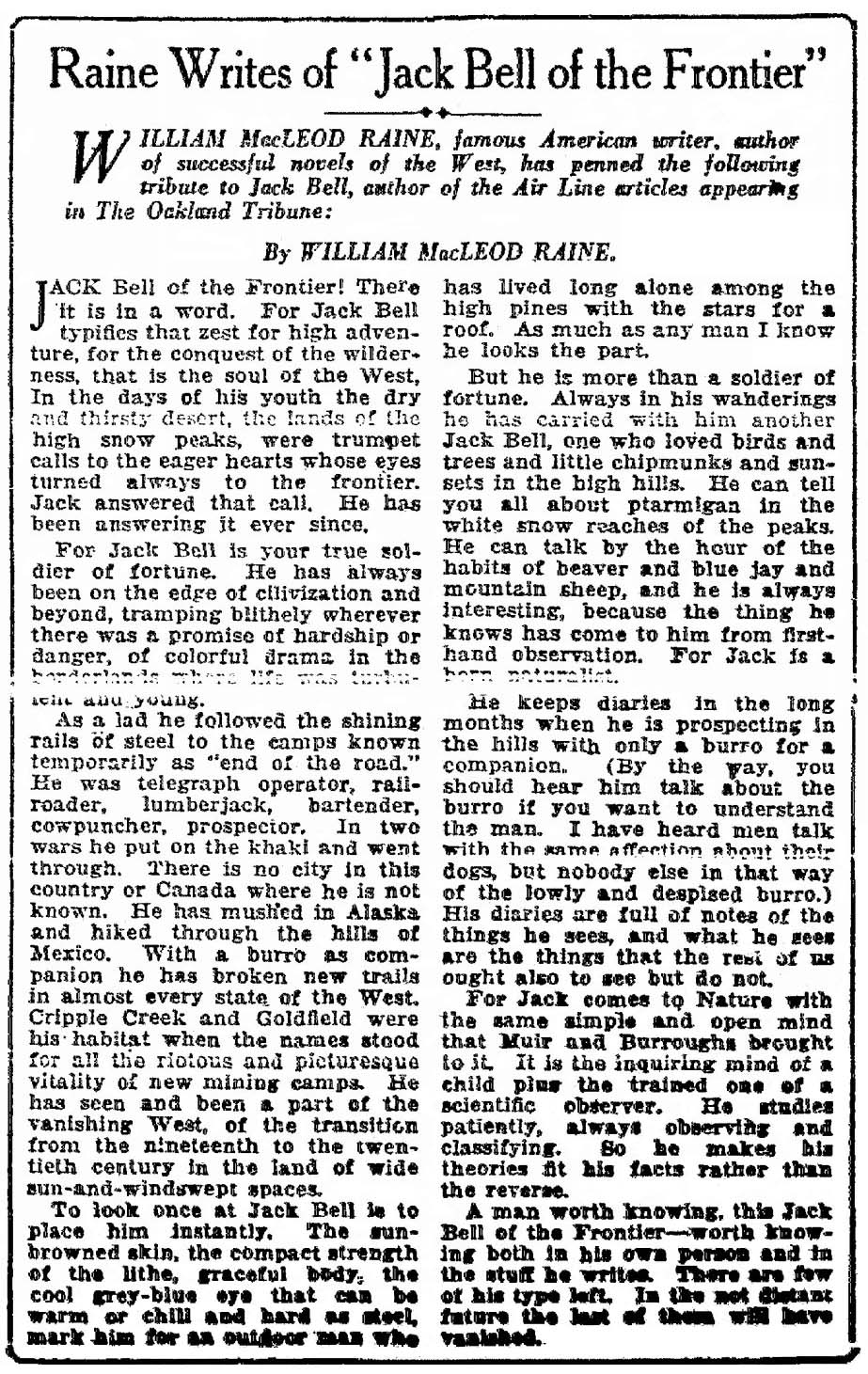

He was witnessing the heroic battle against a 100-mile hurricane by Pilot Burr [H.] Winslow in his famous speed-distance ship 158 (the ship that holds all records for

distance flown and all records for speed, except one for the Transcontinental Red Line air road), thousands of feet above Reno

in the murky spume of mists in the gathering of the full forces of the terrific storm that shortly followed.

Above, far, far above the earth, the monstrous silvered petrel of the clouds stood stationary, and the glints of the lustrous body could be

seen, hanging and shivering, like a living, lost and frightened creature from another world.

As the flashing hurrying mists drove by the seeming suspended ship, a small speck of dark could be marked as the airman out in the cockpit.

The struggling plane was being manipulated by this driver with sinews of steel and muscles of seasoned hickory, with the nerve and initiative

acquired in his signal achievements of past performances in dangerous situation.

But never before had this sky scooter been called upon to meet a like condition of such extreme danger.

Overhead and covering the entire sky, high up and beyond the quivering man-made bird, the dense black clouds moved with the

velocity of light. The thunder roar of the billowing mists, angry and white-rimmed, swirled through the sky with momentum incalculable.

Along the Sierra peaks there was a wide stretch of clearness, confined to the width of the tops of the range, an unheard-of and unusual circumstance.

A scene creating a Dante's Inferno.

Here was an electron striving and fighting against the supremacy of the thunder and storm gods, a vision, a picture in that sky that will make lasting

impression of such vividness that it will never be effasced from the memory of those who witnessed it.

Hundreds of people between Reno and Verdi, 14 miles away, watched breathlessly, and with straining eyes, and shortened breaths, the battle, expecting every second to see the tragedy that it

seemed would issue and become a broken hurtling mass earthward.

The telephones at the Reno field were busy with anxious inquiries.

From many ranch houses were sent the alarm to Manager Tomlinson that a ship was in distress and seemed to be actually suspended by some invisible force

in the misty dome under the blackness of the rising storm.

A woman at Verdi, hysterical from watching the struggle, called the field and cried in a voice of frenzy:

"Please! Can't you send help to the man in the aeroplane? I have been watching him struggle in the hurricane and be tossed about like a wisp of wild cotton

right above our house. He has been driven back like a flash of lightning time and time again. Then he comes back

and right over our house the aeroplane stands still.

Then it backs away toward Reno like a wink, then it comes back again in the same place.

It's just awful, and I know that the poor boy is going to be killed.

There is nothing human that can stand that cyclone, tearing away even the stunted timber along the rims of the low hills."

This is but a sample of the anxiety and pleas that came into headquarters during the one full hour and a half that Winslow made

his fight, a fight that will stand as a record in the official log of the Reno Air-Mail field.

The weather did not seem so bad when he took off at the field on the afternoon of January 27, 1923.

The "Hump" did not look much worse than it generally does when there is a bit of change of weather during the storm season.

The hurricane tore in from the west and a bit north - a cross wind that is the most difficult to negotiate from this field.

There was no warning of the high velocity.

It passed in sweeps up over the highest sawtooths of the range, and then in a down current swept along the eastern slopes

of the foothills and on into the canons to the south and east in the extreme western end of the great basin wherein Reno is situated.

The speed attained was rated by instruments on Winslow's ship when he ran into the teeth of the blow at nearly one hundred miles an hour.

Over Verdi, the intersection of the hundreds of miles of numerous canons and broad waste valleys, the storm center broke, as it always does,

with the fury of a million fiends turned loose.

The first try of the gallant pilot was made from the field southerly.

Then he headed his craft toward the regular Red Line air road, over the hell spot at Verdi, where all the ships take in and out.

This is the route that must be traveled to make the crossing over the "Hump" and at the same time be in reasonable reach of the railroad that, snake-like, winds in and out through

the canons and hills, through the passage of the "Hump," and in view of the miles and miles of snowsheds.

On this first try Winslow made an altitude of 13,000 feet.

When he struck the bumps over Verdi he was almost catapulted from the cockpit.

Then his struggles began.

He had often hit these impacts that are as severe as going full force into a mountain of granite.

Bump, Bump, smash, he went into them.

He used every known experience he has gained to keep the ship from losing speed, going off on a wing and then into the deadly tail spin,

that ordinarily spells death to the pilot and a complete washout of ship as well, even to demolishing the motor,

which would of a certainty happen if the ship were to spin down into the maw of the granite monoliths thousands of feet below.

The deceiving part of the "Hump" was that just a rim of dense black clouds showed along the tops of the mountains.

The pinnacles and roundtops and shattered spires showed through, and the sky seemed to be clear.

Traveling beyond this line looked all right from the air.

There was safety if he could but get out of the maelstrom of angry, uncontrollable winds.

The blasts ran wild, and the driver imagined that they came from every direction of the compass.

However, the ship waded and tore through for about a quarter of a mile, right above Verdi. There she stopped.

Just as if she was tied to a snubbing post she had halted.

"My old boat stood still for what appeared to me an hour," said Winslow.

"Say, that Verdi hellhole ought to be arrested and put away forever.

Well, the blasts began to hit the ship just like an old swamp angel with an extra dose of the ague.

Never in all my flying did I have the queer sensation that resulted from that long, stationary tie-up.

It was weird and most inhuman.

I might have been in another world for all the feeling of ordinary sensibilities that encompassed me.

"It was a new situation. There was danger of being turned upside down, assuming all the positions a ship

may take to end in disaster.

I had the time of my career in keeping her snout down so she wouldn't go dud and into a spin.

But, believe me, I worked.

Then I began to recede, slowly at first, and glancing at my clock I saw that when I looked over the side for a second I was again

over Reno.

It shook me up a bit. I had lost 6000 feet of altitude, too.

"I still had hopes that I would make the crossing over the "Hump" and get the mail down to San Francisco.

I circled the great Truckee meadows and again started for the "Hump."

"I zoomed her right up in a southerly direction until I reached 14,000 feet. Heading the ship toward the Verdi hell-hole again,

I quartered and went into it again from over Reno, in nothing of time.

The crash I received the first time was terrific - never had such a pound against a ship. I thought for a minute that she would fly to pieces.

"Say, right here we all have to hand it to the 'Motor Macks' for their care of these sky trailors.

They make them safe.

When a ship can stand what the 158 did, why there is nothing in the heavens that can destroy one of them.

They always function, and we all know it.

"Well, I stood still again in that spot.

The wind whistled like thousands of lost souls.

Sprang, sprang, Aeolian harps, intensified hundreds of thousands of times, were in the twang the wires made.

The covering of the wings seemed to flatten down to thin paper thickness.

All over the ship there appeared to me weird changes that I had never before imagined could be possible.

The darn business kind of got my goat for a while.

I was determined to get that mail down to San Francisco if there was the remotest chance.

"All at once I noticed that the altimeter was dropping at an alarming rate. The down current coming

from off the high Sierras swept up and rolled in great billows, about like Niagara I figured out.

I was back at Reno again.

It was just whang, and the ship was again over the city.

It had been pressed from 14,000 down to 8000 feet.

"Around the meadows, over Sparks, I again took her, stepping on her.

I went up to 13,000 again and swept her into the hole at Verdi again.

No getting past that barrier of savage, intense wind that I had already found was over a mile thick - that is, this hurricane

was that intense through this measurement.

As a matter of fact, there was no top or bottom that I could find.

"At the third and last try for the crossover, I noticed that the "Hump" had darkened and was black as

night over the entire range.

At that I took another chance, believing I might get through.

I made Verdi again.

It was worse than ever.

I succeeded in turning the ship again and came back to the field.

Doggone tough luck, not getting the mail down!

Makes me mad when I default!

We have enough troubles without failing to get the mail across.

But when you can't, you can't, and that's all there is to it.

"I am mighty glad that I did not have a passsenger up there on that trip.

It would have worried me for his safety."

January 28, 1923, will always be remembered by the United States Air Mail service, and by each member of the personnel at Reno and

San Francisco, as having the most remarkable condition of wind and hurricane directions in the history of the U.S. Weather Bureau.

It is very doubtful if this exact condition will ever obtain again.

Over and along the topmost crests of the peaks of the Sierra Nevads, for a distance of about one hundred miles, easterly and westerly,

the sky was clear and bright.

The condition was described by the two pilots, Winslow and [Claire K.] Vance, who made identical weather reports, details the same air hazards, told of the

awful battle they had - how their ships stood stationary.

Each one of them told of the terrific currents of air coming down on top of their planes, and how their altitude dropped thousands of feet in a fraction of time.

They related how they made the three attempts to reach their goal, the famous "Hump," how their ships sang and trembled, and how the

400 horsepower Liberty motor was as an ant hurtling its puny self against a locomotive under full headway.

There was but one startling exception in the reports and tales of their united, parallel experiences on this banner day of days.

Winslow fought against a wind that came out of the west, by a bit north.

Vance made his great fight against the elements that blew from easterly to a few points northerly.

This was due to a weird, abnormal splitting of the hurricane by the colossal row of peaks along the Sierras.

There was created a complete change in the direction of the hurricane.

As shown by the reports of these two airmen, the great width, depth and height of the wind flow was actually split and changed in opposite directions.

The two pilots were doing the same things at the same time and they were over one hundred miles apart in an air line.

Neither man knew of the battle of the other until the next morning.

It was then that even they were dumfounded, and only after long arguments were convinced that the wind had blown in different directions,

divided by the Sierras.

Pilot Clare K. Vance left the field at San Francisco on this same day and at the same time as did Pilot Winslow from the Reno field, on the afternoon of January 27.

Vance came along at record-breaking clip on the wings of a fair westerly wind until he reached a point within a few miles of Colfax, Calif., Colfax being about air line

distance from the "Hump" as Verdi is from Reno.

It was here that he ran smack into a bump that almost unseated him with the shock of a liner striking a submerged iceberg.

Then the battle began.

After the first attempt to negotiate the roaring flow of winds,

Vance found himself standing still in the air, immobile, with the grand Liberty motor holding its own, against the

pressure immeasurable, unknown, singing its song in the long roar of combat, in defiance to the kings of the whirlwinds.

The ship shook and wavered with the jumpy increase of the raging element.

With masterful courage Vance watched for a method of deliverance.

The change came with suddenness that could not be timed.

The wave of energy came from above and struck the ship with an impact terrific, and down and back

the plane flew.

With experiences supreme, the ship was headed tail-to.

In less time the ship was again over Sacramento at 8000.

Around the edges, Vance zoomed up, and up and up until he calculated he had reached the ether above the wind flood.

Then he guided his ship for the straight line over Placerville and Colfax for the "Hump."

Into the cauldron of mixed and varying bumps he sped and with a crash he again landed against the full force of the gale.

The crash tried both pilot and ship.

Over Colfax again the same air conditions remained unchanged from those which he had experienced just minutes before.

He turned the giant bird again and with the speed of a moon trail on the hills he again found himself at Sacramento with loss of altitude again.

It seemed inconceivable that the "Hump" could not be reached when it was so clear and bright from the vantage of 12,000 feet above the earth.

Once more this wonderman headed back up into the altitudes and reached 15,000, and hoped to take the flight with his mail into Reno and not default.

Again when he reached the holes and bumps and terrific pounding of the screeching winds, went through the same trying, exhausting fight, and saw that the dense black clouds

were beginning to envelope the mountains from every direction, he gave it up.

But he had made his fight that will go down with Winslow's as the most gruelling, most unusual and thrilling experiences that flyers can experience,

here over the dreaded hundred miles of territory where there is absolutely no landing without death, and where the elements are always vieing with each other to encompass

and destroy these aces of the U. S. Red Line road.

No rating is too high, no compliements are too great for those men who fly the "Hump."

Vance then landed his plane at Sacramento, put his cargo of mail on a limited train and headed his ship for San Francisco.

Strange again are the freaks of the winds.

Starting toward his home field he ran into west winds that slowed him up and made his journey back as difficult as many of the trials in the

fights over the mountains.

The good old Liberty motor growled through, but it took one hour for the 90 miles.

The log books at this field have material enough to make a thousand movie thrillers and no picture ever taken could half

depict the courage, dangers and hardships experienced by these unsung men of this branch of governmental service.

Pride in service - 100 per cent mail carrying - is the slogan of the Reno air mail field.

The crux of the entire success of every flight made is the care, attention and personal feeling and labor

put upon the ships and the great motor, the careful servicing.

This is the seed that makes the rest of the vast plant grow and have its being.

Added to this that feeling of knowing that all that is humanely possible has been done for the safety of the pilot when he takes

his ship into the air is the outstanding factor of success of that very same flyer. If there was a little doubt in the mind of the

pilot that his ship had been neglected in the least bit he would naturally be worried.

This would of course retard his performance in his line of duty.

But there is nothing but that absolutely trustful understanding among the entire personnel along the western divisions, and of course the same conditions must prevail

all along the Transcontinental air road.

The craftsmanship of the "Motor Macks" on Reno field and San Francisco field has proved to the world that the technical knowledge and genius of workmanship

are there. They have invoked front official Washington recognition of the master care of motors and the perfect construction of the standard De Haviland type of ship

[xx] presented the magnificent compliment of being perfect in efficiency of its personnel under the direction of Major O. A. Tomlinson,

field manager and his incomparable assistants.

San Francisco is mentioned about on par under the supervision of Assistant Superintendent Lafollette and his expert array of "Motor Macks."

The staffs at Reno and Marina fields are justly proud of this distinction, of the road sweeping appreciation of their careful labor,

and inspection of the world-famous ships that fly over the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Major Tomlinson has received official notification from the Postmaster General at Washington that the United States air mail was the

recipient of the Collier aeronautical trophy.

This prized award is the most sought of all the cups and rewards given to every branch of aeronotics in the United States.

It means that tho United Mates air mall has the recognized unbeatable aggregation of experts with resultant accomplishment in this country.

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen