The Republican Court Or American Society in the Days of Washington, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, 1856, p138

The Republican Court Or American Society in the Days of Washington, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, 1856, p138

The anxiously expected morning of Thursday, the thirtieth of April, was greeted with a national

salute from the Bowling Green, and at an early hour the streets were filled with men and women, in

their holiday attire, while every moment arrived new crowds from the adjoining country, by the road from

King's Bridge, by ferry boats from more distant places, or by packets which had been all night on the Sound or coming down

the Hudson. At eight o'clock some clouds about the horizon caused apprehensions of an unpleasant day; but when,

at nine, the bells rung out a merry peal, and presently with a slower and more solemn striking, called from

every steeple for the people to assemble in the churches "to implore the blessing of Heaven on the nation, its favor

and protection to the President, and success and acceptance to his administration," the sun shone clearly down,

as if commissioned to give assurance of the approbation of the Divine Ruler of the world.

As the people came out from the churches, where Livingston, Mason, Provoost, Rodgers, and other clergymen,

had given passionately earnest and eloquent expression to that reverent and profound desire which filled

all hearts - so universal was a religious sense of the importance of the occasion - the military began to

march from their respective quarters, with flaunting banners, and the liveliest music. The principal

companies were Captain Stake's troop of horse, equipped in the style of Lee's famous partisan legion;

Captain Scriba's German Grenadiers, with blue coats, yellow waistcoats and breeches, black gaiters,

and towering cone-shaped caps, faced with bear-skin; Captain Harsin's New York Grenadiers, composed, in initation of the

guard of the great Frederick, of only the tallest and finest-looking young men of the city, dressed in blue

coats with red facings and gold lace broideries, cocked hats with white feathers, and white waistcoats

and breeches, and black spatterdashes, buttoned close from the shoe to the knee; and the Scotch Infantry,

in full highland costume, with bagpipes.

Ralph Izard, Tristram Dalton, and Richard Henry Lee, on the part of the Senate, and Charles Carroll, Egbert

Benson, and Fisher Ames, on the part of the House of Representatives, had been appointed a joint committee of

arrangements, and the procession was formed under the immediate direction of Colonel Morgan Lewis, in Cherry street,

opposite the President's house, at twelve o'clock. After the military came

The Sheriff of the city and County of New York,

The Committee of the Senate,

George Washington,

The Comittee of the House of Representatives,

John Jay, Secretary for Foreign Affairs,

Henry Knox, Secretary of War,

Robert R. Livingston, Chancellor of the State of New York,

Distinguished Citizens.

The procession having marched through Queen, Great Dock, and Broad streets, until opposite Federal Hall,

the troops formed a line on each side of the way, through which the President, with his attendants, was

conducted to the chamber of the Senate, where the members of the House of Representatives had a few minutes

before assembled, and at the door the Vice President received him and waited upon him to the chair.

The Vice President then said, "Sir, the Senate and House of Representatives of the United states are ready

to attend you to take the oath required by the Constitution, which will be administered by the

Chancellor of the State of New York."

The Vice President then said, "Sir, the Senate and House of Representatives of the United states are ready

to attend you to take the oath required by the Constitution, which will be administered by the

Chancellor of the State of New York."

The President answered, "I am ready to proceed."

The Vice President and the Senators led the way, and, accompanied by the Chancellor, and followed by the

Representatives, and other public characters present, he then walked to the outside gallery, from which Broad street

and Wall street, each way, were perceived to be filled, as with a sea of upturned faces, but as silent as if the

immense concourse had been statues instead of living men.

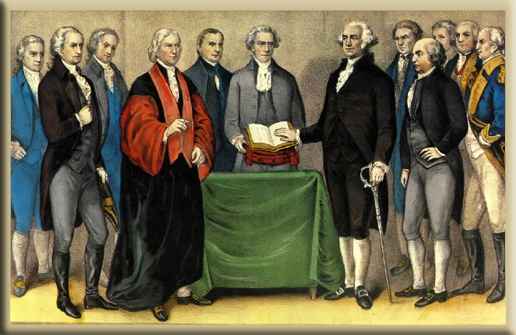

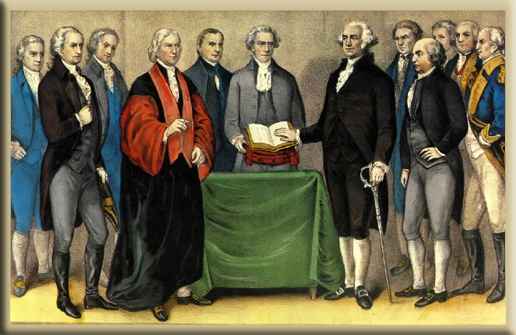

The spectacle must have been in the highest degree interesting and serious. In the centre, between two pillars,

was seen the commanding figure of Washington, in a coat, waistcoat, and breeches, of fine dark brown cloth, and

white silk stockings, all of American manufacture, plain silver buckles in his shoes, his head uncovered,

and his hair dressed in the prevailing fashion of the time. On one side stood the Chancellor, in a full suit

of black cloth, and on the other the Vice President, dressed more showily, but like the President entirely

in American fabrics. Between the President and the Chancellor was Mr. Otis, Secretary of the Senate, a small

short man, holding an open Bible upon a rich crimson cushion, and conspicuous in the group were Roger

Sherman, General Knox, General St. Clair, Baron Steuben, and others whose names were equally dear and familiar

to the people.

A gesture of the Chancellor arrested the attention of the immense assembly, and he pronounced slowly and

distinctly the words of the oath. The Bible was raised, and as the President bowed to kiss its sacred pages,

he said audibly, "I swear," and added, with fervor, his eyes closed, that his whole soul might be absorbed in

the supplication, "So help me God!"

Then the Chancellor said, "It is done," and, turning to the multitude, waved his hand, and with a loud

voice exclaimed, "Long live George Washington, President of the United States!"

Immediately the air was filled with acclamations and the roar of cannon; the President bowed, and again and

again the welkin rung with the plaudits of happy and grateful citizens, who felt that Heaven had granted

all their reasonable petitions, and that the New Era dreamed of by sages and celebrated by orators and bards

was now completely inaugurated.

"The scene," writes one who was present to his correspondent in Philadelphia, "was solemn and awful beyond

description. It would seem extraordinary that the administration of an oath, a ceremony so very common and familiar,

should in so great a degree excite the pub.ic curiosity; but the circumstances of the President's election,

the impression of his past services, the concourse of spectators, the devout fervency with which he repeated the

oath, and the reverential manner in which he bowed down and kissed the sacred volume, all these conspired to

render it one of the most august and interesting spectacles ever exhibited. ... It seemed, from the number

of witnesses, to be a solemn appeal to Heaven and earth at once. In regard to this great and good man I may

perhaps be an enthusiast, but I confess that I was under an awful and religious persuasion, taht the gracious

Ruler of the Universe was looking down at that moment with peculiar complacency on an act which to a part of his

creatures was so very important." Under this impression, he proceeds to say that when the Chancellor proclaimed

Washington President, his sensibility was so excited that he could do no more than wave his hat with the rest,

without the power of joining in the repeated acclamations which rent the air.

Few persons are now living who witnessed the induction of the first President of the United States into his office;

but wlaking, not many months ago, near the middle of a night of unusual beauty, through Broadway - at that hour scarcely

disturbed by any voices or footfalls except our own - Washington Irving related to Dr. Francis and myself

his recollections of these scenes, with that graceful conversational eloquence of which he is one of the greatest

living masters. He had watched the procession till the President entered Federal Hall, and from the corner

of New street and Wall street had observed the subsequent proceedings in the balcony.

|

![]() Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises

Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises