Chapter 3. Poetry and Boose, or A Night at the Village Vanguard

In 1935 Eli Siegel was the master of ceremonies at the Village Vanguard. He ran the show

and introduced the poets and the Village personalities who made their home at the Vanguard.

Maxwell Bodenheim, John Rose Gildea, Joseph Ferdinand Gould, Genevieve Larssen, Harry Kemp,

Jack Sellers, the National Maritime Union poet, and others, published and unpublished.

He'd bring on Abraham Lincoln Gillespie, Jr., the "Poet of Sputter," Eli called him. Eli

explained that Link hailed from Philadelphia, "has been living in Paris for several years --

an exile in Paris -- but is back in America now and has taken up residence in Greenwich Village.

Link will recite his famous Dada poem he brought back from Paris with him, 'Willow Cafeteria.'

I don't want you to miss a word of it, so please be quiet," Eli warned.

Link would rise, lay down his cigarette, decline the spotlight and, in a mighty voice, start his famous poem,

"Willow Cafeteria." It lasted three minutes -- a clangorous babble of a busy, crazy kitchen, dishes

crashing, pots and pans exploding, all mixed with stentorian cries of distress. Link had the voice for it.

He'd stop as suddenly as he began, bow, and sit down. This was a major nightly event, and never failed

to bring down the hosue.

Eli was famous for having won the 1925 Nation magazine poetry prize for

"Hot Afternoons Have Been

in Montana." But he'd begin the nightly proceedings with his shorter poems or a poem by Vachel Lindsay,

his favorite American poet. But when the requests got so hot that the audience couldn't be

denied, Eli would consent to recite his famous prize winner. This was a signal for the hecklers.

"When were you in Montana on a hot afternoon?" they'd cry.

Eli knew how to handle hecklers. "I wasn't in the Ford Theater when Lincoln was shot either.

I know he was shot. You know he was shot. Who said you gotta be in a place to write about a place,

wise guy?"

Hooting, laughter, and applause. It was all part of the fun, part of the action. You came to the

Vanguard to hear the poets, watch the characters, get loaded, and heckle Eli.

In addition to poetry, there was music and the dance. Mascato, the house operatic baritone, sang, mostly "Figaro"

from The Barber of Seville, which brought a shower of dimes, quarters and half-dollars

hurtling at his feet. I stood around with a quarter in my hand to shill for him.

Then Maggie Egri, the hat-check girl who doubled as songstress, and Oronzo Gasparo, an artist

by day and Vanguard waiter by night, were introduced by Eli. Their big number was "Rose of Washington

Square." Maggie carried Oronzo piggyback off the dance floor at the end.

During the intermission a radio played dance music. Since the Vanguard didn't have a liquor

license, people brought their own and ordered glasses, ice and soda.

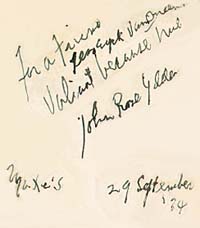

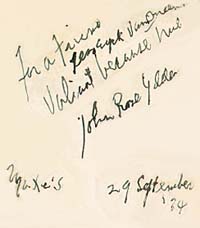

John Rose Gildea was welcome at every table. Joe Gould too, if he was looking for a drink.

Bodenheim kept a pint bottle hidden in his back pocket. He sneaked his drinks in the men's room.

Eli never took a drink, which didn't endear him to the other poets.

Eli would stand waiting for the audience to grow quiet so that the show could go on.

He was not a sunny, happy, loquacious M.C. He needed quiet and, by God, he was going to get it.

"I shall begin by reciting the shortest poem in the world:

I.

"Why?"

This set off a wave of hooting and hilarity. "Who? You?" echoed from every corner. Eli would

stand firm and wait for the noise to subside. "I will now recite the second shortest poem in

the world:

"Jones Moans."

Laughter and applause.

These were the years of deepening depression. You could spend a night at the Vanguard for a buck.

If you were broke and a member of the Greenwich Village Cafeteria Society, you were in free.

A promise not to go around with a glass in your hand, mooching drinks, was the price of admission.

Eli, pale, bent, dour, with the look of a Hasid, kept the show moving. I paid him thirty a week.

Eli had to catch Gildea early if he was going to get him to recite; otherwise John was asleep

in a chair. Eli liked John, as one poet to another, despite John's drinking habits.

"'The Roue Moon,' please, John" Eli'd prompt him as John labored to the floor. John not only was a

poet, he looked like a poet, people said on seeing John for the first time.

"I wrote this poem when I was drunk," John would say introducing it.

"The roue moon wears night like a high hat -- hey! hey!

The ribald moon carries a graceful shaft,

malacca stick -- how! how!

malacca stick -- how! how!

The unsteady moon throws night its opera cloak

Giggling with stars -- ho, hum"

"That's poetry! That's real poetry!" Eli would say as John sat down. "Thank you, John."

Eli'd then squint around the room to see who was in a condition to go on next. If no one was

ready, he'd do a couplet of his own, this time in Yiddish.

"a fa-SHIST

Passt NISHT"

(Translation: A fascist is unbecoming, an embarrassment.)

"Joe, where are you?" Eli would then shout. "Ladies and gentlemen, the Harvard terrier and

boulevardier, Joseph Ferdinand Gould!" How did Joe Gould deserve these might accolades

bestowed by Eli? Joe was a Harvard graduate, class of 1912, five foot three inches tall and weighed

ninety pounds. He was a man of poverty and dignity and was quick to take offense. If he

felt patronized, he'd invite you outside. Thus his nickname "Harvard terrier." As for

"boulevardier," that's because Joe always sported a long cigarette holder.

Eli's introductions tended to be descriptive and demeaning.

It took Joe a little while to get into the amber spotlight where Eli was waiting. He had first

to find a safe place for the dozen or so grammar school composition books he was always

carrying around, the manuscript of his History of the World from Oral Sources,

a work that had been in progress for twenty years when I first met Joe in the Village.

It took four years at Harvard to make me what I am today." Joe would begin.

"People sometimes ask me how I live. Air, ketchup, self-esteem, cowboy coffee, fried-egg sandwiches,

cigarette butts -- what else is new? What's my religion? I'm from New England.

In the winter I'm a Buddhist, in the sumer I'm a Nudist. And now you can make a contribution

to the Joseph Ferdinand Gould fund if you care to. You can find me at a table later."

Bodenheim, pacing and scowling in the back during Joe's performance, would stop suddenly, point

his finger, and shout, "Eli Siegel! I hate you, Eli Siegel. You rat!"

Bodenheim didn't like Joe Gould's self-demeaning performance and blamed Eli. The audience hooted

and applauded. Eli would then call John to the floor again to join Joe for the poem that was

to follow, and also call up Professor Woodman, "who happens to be visiting us tonight." The

professor, an instructor in literature at the University of Iowa and a secret poet, never failed

to visit the Vanguard when in New York.

"The next poem is 'Ambition.' 'Ambition,'" Eli explained, "is a poem that has to be

recited by three poets."

Gildea then assumed the role of spokesman.

"Quiet, goddamit!"

Gildea liked to do this poem because Professor Woodman, his friend, "who wrote it, is here tonight"

and further because "Ambition" not only took three poets to recite, as Eli rightly said,

but it was a poem that had to be assaulted, beaten, by God, to extract its full, its glorious meaning.

"So quiet, goddamit!"

Joe, John, and the visiting professor from Iowa lined themselves up, their right arms extended, poised

as if about to administer a karate blow on some hidden target.

"Ambition," they'd cry, and down came their arms in anger on the unhappy word. Then together:

"What?

Have we?

To do?

With that!

Foul bitch!

That Stinking!

Witch!"

By this time their shouts and flailing arms raised so much heat that the rest of the words got

lost, and it was a good time to call another intermission to cool the place down, which Eli did.

To get the Vanguard quiet again after an intermission was no easy matter. Many times Joe Buff,

the bouncer, and I would have to throw a couple of characters out of the place.

Eli liked to interject a note of seriousness, a lesson to be learned at this point:

"It often happens with a floozy

When tired and maybe boozy,

She sees her past and gets quite woozy."

What effect Eli's rhymed warning had on the customers is hard to say.

Eli would wait for Bodenheim to shape up so he could call on him to recite. But it was no use.

Bodenheim, swirling crazily, eyes glazed, arms outstretched, would suddenly stop and point

his finger at a frightened girl who had refused him a dance during intermission. "Rat!"

he'd shout at her.

So, despairing of Bodenheim, Eli called on Baudelaire instead, and someone in the room shouted,

"Is Baudelaire here tonight?"

"No, Wise guy, Baudelaire isn't here tonight, but he was a famous French poet, and I'm going to

recite one line out of one of his poems, if that's all right with you," Eli said, his

eyes riveted on the heckler who dared to interrupt him. "He wrote, and I quote, 'Anywhere,

anywhere, out of this world.' That's a fine Village sentiment, but Baudelaire took hashish and destroyed

himself. Think about it."

This serious mood upon him, Eli continued. "Take Edna St. Vincent Millay. She wrote some beautiful

poetry. She wrote about burning a candle at both ends, which makes a lovely light. All very nice,

very lovely, very Villagey. I don't know how you can burn a candle at both ends that makes a

lovely light. I never tried it. But, to her credit, Edna St. Vincent Millay also wrote a serious

poem about Sacco and Vanzetti.

"You don't know that, do you?" Eli'd say, his eyes still on the unhappy heckler.

About this time Harry Kemp, drunk -- you could hear him outside calling my name -- would come roistering

down the steps. "Where are you, you old sonofabitch? Where's my wine? Where's the glass of

wine you promised me, you old bastard?"

Harry, six feet tall, barrel-chested, hair over his eyes, would grab my shoulders and plant a kiss

on my forehead. "Sit down a minute," he'd cry, pulling me toward a chair.

"That's Harry Kemp!" Eli would call out. "A fine poet and the author of 'Tramping on Life.'"

Some earnest tourist, at hearing Harry Kemp's name and anxious to be of help, would come forth,

a glass of wine in his hand.

I don't want your wine," Harry'd shout at him, then place his head on his folded arms and sob.

"I don't want your goddam wine!"

Towards the end of an evening, Eli liked to call on Bob Clairmont, known in Village circles as a

millionaire playboy-poet. The story went that some years before, Bob, tall, handsome,

muscular, when employed as a lifeguard at a private beach on Long Island one summer, had taught an

aging corporate executive how to swim. The executive died and, out of simple gratitude, left

Bob a million dollars in his will -- or was it only four hundred grand as some Villagers claimed?

It didn't matter. It didn't take Bob long, with the help of his Village cronies, to fritter away

that fortune. Bob, now broke and a poet, had the privilege of a free pass to the Village Vanguard.

Bob was too shy to recite his own poetry, so Eli never pressed him. Instead, Eli recited portions of it:

"When I am bald and dead,

With my silk hat in my hand,

To the hungry worms I'll say,

You still don't understand."

Eli liked to lay these chilling lines on the crowd that had raised so much hell all night.

It all added up to a night at the Village Vanguard, a night of Greenwich Village high jinks,

of poets, WPA. writers, hustlers, insomniacs, college students from the Bronx and Brooklyn,

tourists, broads on the make, musicians, moochers, all of them crowding the place every night

to let off steam.

I was at the Vanguard every night. I had to be, or the joint might have blown up.

But when I wasn't looking, or so it seemed to me, a lot of guys and gals who didn't belong in

the place began to find their way to the Vanguard. Stags from New Jersey and the Bronx, dropouts

from MacDougal Street, Irish kids from Hudson Street, all walked in carrying bottles in brown

paper bags. (I still didn't have a liquor license.)

How it happened I didn't know. I didn't run any ads; I didn't have a publicity man. They didn't come to

hear Eli and the poets. They came to drink beer and raise hell in the Village. And wise guys and

pranksters started coming around to drive me crazy.

And on top of everything else, Eli was growing more dour and cranky than usual. Instead of

sparring with the hecklers for laughs like he used to, he'd come down heavy on them, scold and

snort as if he wished they were somewhere else -- not at the Vanguard -- and that he too, God willing,

was somewhere else. It was enough. The Vanguard was due for a change, I told myself. Get rid of some

of the customers, get rid of Eli, get rid of the poets and poetry and put some prose into the joint.

So I did.

Eli later became the founder, leader, guru, rabbi -- take your pick -- of a movement he called

Aesthetic Realism. Don't ask me what aesthetic realism is about. He ran it from a store on Greene

Street in the Village. And he had a host of believers who followed the teachings of Aesthetic Realism.

He was putting this movement together when he was the M.C. at the Vanguard. He told me this once when

I ran into him on Jane Street almost forty years later. I didn't believe it.

"You need Aesthetic Realism in your life," he said, looking me in the eye. "I know the kind of

man you are. It'll straighten you out. And not only you -- it can straighten out the whole world.

Aesthetic Realism can straighten out the whole world, if ony the world will listen to me."

I see now what ailed Eli when he was the Vanguard M.C., why he was always getting so mad at the customers.

He was trying to straighten them out, that's what he was doing. It's a good thing I got rid of him.

One thing I learned in almost fifty years of running a club in New York: You don't try to straighten

people out in a nightclub. You leave them alone and hope they'll leave you alone.

![]()

Copyright © 2001, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2001, Mary S. Van Deusen