Can Airplane Leap 2700 Miles from San Francis

to New York in Twenty-one Hours?

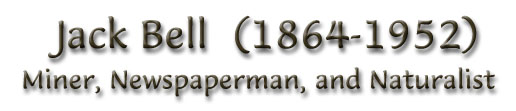

By Jack Bell

ONE jump to Gotham - that is the plan of Claire K. Vance, famous U. S. air mail pilot,

who is at this moment putting the finishing touches to his great new "mystery ship" at Reno.

Vance plans to fly from San Francisco to New York without a single stop.

Vance will fly alone, to conserve weight and gasoline.

He will be at the pilot's controls for more than twenty hours without sleep.

Discussing his plans for the first time the airman said:

"If I have no bad luck I will have the ship all tested and ready for my try at the non-stop transcontinental trip on April 1.

"The ship will rate 130 miles an hour.

My tentative route I have already worked out.

"I will leave San Francisco from the Air Mail field at noon.

I will cross the Hump and fly in a direct line for Rock Springs, Wyoming, 750 miles away, where I should arrive at 6 o'clock in the evening.

Then I figure nine hours of night flight will bring me over Chicago, with the hour advance in time, arriving over the lake city at 5 in the morning,

and at noon on this same day should reach New York, my final destination.

"This will make the entire cross-country, coast-to-coast run in twenty-one hours.

It would involve twelve hours of daylight flying and nine hours night sailing.

"Of course this tenative program depends upon weather conditions and perhaps many other conditions that will arise.

It will be no sinecure - a sustained flight like that.

My night flying will be over reasonably level country, and will be straight away.

Of course, I have figured upon the moonlight night for the trip.

"In the matter of feed?

I will carry sandwiches and have good strong tea for a stimulant.

Yes, tea will act as a stimulant, because I have never used coffee or tea in all my life.

"I realize that I have undertaken a big job.

I know that I will have a lot of heart-breaking experiences even before I make the ship ready for test, and the ride will not be a bed of roses by a long shot.

It is a pretty big job for a man who works for wages and does very nearly all his own work.

But long ago I had ideas and theories about a ship that would make the sustained flight across the entire United States.

There is no reason that I can see why I cannot make the run.

"It's no easy thing for one man to figure and plan and to create a plan for work like this.

I have been diligent for many months working out many new [xx]

that I don't care to discuss at this time.

If I am successful and arrive at New York something near the time I have worked out I will then make public the innovations that I had added to the ship's construction.

"The only thing that has worried me is to get the altitude to get over the Hump - if that's successful I will be 'Jake' and have no hesitancy in saying that I

will make New York in the twenty-one hours continuous flight.

As a matter of fact, as the gas is consumed the ship will have easier headway and as I near the end of the journey I will know how much trottle I can give her, and

- well there are a heap of suppositions - a heap - and I feel confident that I will do the job."

Tales that Vance tells of near flyers making suggestions are amusing.

He listens to them all.

He has callers at his shed where he is building daily.

He listens patiently, but it is only when one may offer a new idea that he absorbs the chatter of the knowalls.

So far, the many busy alleged flying men from outside his circle of staunch supports of the mail mail personnel have annoyed him considerably,

but he is of long suffering, and thinks that even an unitiated may drop some seeming ordinary suggestion that might be valuable.

His friends are a unit their belief that he will make a successful trip.

Clair K. Vance Works on Mystery Ship

to Break Record for Sustained Flight

There have been many stories of the ship under construction by Vance.

He tells for the first time in detail about his work on the plane with which he hopes to make the record non-stop flight.

"I started building the ship last September.

The most of the actual construction is about complete.

Now the work will start covering the wings, and then the assembly, rigging, as in any other ship.

"The fuselage is 25 feet long.

All controls are standard. There will be [xx]

connected with the usual baffles.

The third tank will hold 350 gallons of gasoline, weight 2100 pounds.

The oil-carrying capacity will be for twenty-five gallons.

"The motor is the 285 h.p. Salmson, the same motor that was used on observation planes overseas, might reliable and of long life.

The radiator I have sent to Paris for, and will hold twelve gallons of water.

The propeller will be a Salmson and have a length of [xx] feet, or one foot longer than the propellers used on our mail ships.

"The top is a whole wing and has a spread of 39 feet over all.

There is a one-piece wing center section.

The wings are fastened on each side of the center section, making two wings on the bottom

under the fuselage - the same spread as the top wing.

"I will use the German curve, which has never been tried on this side before.

They have all been afraid to try it here on account of the high lift and speed curve.

"The only light on the ship will be on the instrument board.

From propeller to rudder the ship will measure 25 feet.

The feed to the motor will be by gravity, prompted from the main tanks.

The landing gear will be standard.

"The ship loaded will weigh about 4200 pounds when ready for its flight.

"Of course, there will be a lot of work testing the ship out.

The main thing is the height question - the one that bothers everyone who has tried the heavy gas load.

But I feel sure that I have overcome all that with the application of a few ideas of my own.

"When I take the ship up for the tests I will, of course, have just enough gas to make short tests, then I will ballast with sandbags to

acquire the maximum load."

Only recently a signal honor was paid Vance - no less than a personal commendation from the postmaster general - citing the Hump flying man in

such words of praise that are seldom bestowed upon an employee in government service at home.

A citation by telegraph is also an unusual circumstance.

A citation transmitted down through all the regular channels to the recipient of the honor has obtained for the first time in the history

of the air mail service.

The text of the unusual document commands executives to take note and asks the immediate governing official of his division to commend and to think Pilot Vance

for his service in commandeering an army plan at Mather field after [xx] with his [xx]

from near the Hump, where his ship's motor cracked a waterjacket and rendered dangerous the flight.

It tells how he transferred the mail from his wounded silver winged ship, tied the mail on the wings and in the observer's cockpit of the

army plane and proceeded with his flight.

He flew in darkness for twenty minutes and landed at Reno field without mishap to ship or cargo, and delivered the mail on time.

Feburary 6, 1922, Vance took off the field at San Francisco on regular schedule time with a load of 218 pounds of valuable mail.

He was making goood time and in a fair way to reach his destination at least twenty minutes ahead of the usual flying time.

When above Placerville, a waterjacket cracked, throwing the spray in a solid sheet over the ship and into the face of the pilot.

There was nothing for him to do but to try for a landing at Mather field at Sacramento.

He turned the great flying bird about and made Mather and landed.

With speed and argument he prevailed upon the commandant there to lend him one of the regular type observation ships.

This type is fitted with guns, and the cockpit of the observer is behind the pilot - the ship that is used by the signal corps of the service.

After heated requests and persuasive argument, the rules of the army were laid aside and Vance was given a ship, a deHaviland, a rather clumsy, but absolutely airworthy

plane, not of the wonderful speed of the mail ships, but a dependable old wagon that always gets there and does the work.

Of course the ship was not built for cargo carrying.

Vance piled what mail he could in the observer's cockpit, and then with the overflow of several sacks, had them securely lashed to the wings and fuselage.

He took off all right, slow but sure.

He left the field at Sacramento at 4:30 p. m. and slowly made his way over the Hump and came on down through the Verdi hellhole of bumps and landed at Reno

field twenty minutes after twilight.

It was in the dense darkness that he landed.

Strange as it may seem - with a type of ship he has not flown since pre-war days - he came into the field and with perfect assurance made as good a set-down

as has ever been made on Reno field.

The next morning he loaded the army ship, tieing his mail on the wings again, and flew to Mather field, transferred his load to

his own plane, which had been repaired, and delivered his load to his home grounds at San Francisco almost on schedule time.

"Oh, that was nothing; any one of the other fellows would have thought of the same thing to do - anything, any chance to get the mail through, and not default,"

commented Vance.

"It seemed mighty funny to handle one of the army boats after being away from them so long, but it came to me.

She was a bit slow, but the ship was in fine shape and the motor was smooth and fine.

It was slow, with the load she had, but she was a good ship and I was sure a heap obliged to the army folks for their consideration and help

in making my trip 100 per cent.

They were all just fine."

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell.)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen