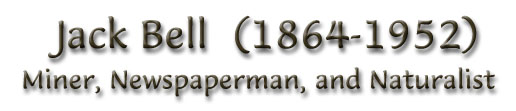

By Jack Bell

For the First Time Air Mail Plane Cannot Go Over Peaks in Face of Blizzard; Forced Down

FEBRUARY 26, 1923, is a date on the log book page at the Reno and San Francisco United States Air Mail fields that is embossed in red ink with marginal

notes setting forth the records of duty done under stress and under weather conditions that vie with those surmounted recently by Pilots Winslow and Vance.

For the first time in history a landing has been made on the Sierra "Hump" itself.

February 26 was a beautiful, bright, warm day down upon the terrain.

Pilot Claire K. Vance took off the San Francisco field at 2:20 p. m. for his run over the Hump to Reno to meet the fast Overland Limited mail train, the

first day's [xx] of the Air Mail for Nevada, Utah and the East.

He was serviced carefully with gas.

His load of mail weighed 300 pounds.

There had been a new motor installed, and the ship went away into the "upstairs" in perfect resounding rhythm of the incomparable Liberty.

The dreaded Hump, that passageway in the Sierras at an altitude of 10,000 feet, where all the ships of the Air Mail make their crossing between California, is a

dangerous place for the fliers when there is any unusual disturbance in atmospheric conditions.

With a heavy snow there is one chance in a thousand that the pilot can land his ship, crack up or crash, or get away with his life.

In the very lap of the Hump are numerous snow lakes.

Their outlets are dammed artificially to hold the water supply for California points.

There are 18 such lakes scattered in a radius of 50 miles over and among the nipples of the saddles where the mail ships make their crossing.

The usual altitude flown to make this passage safe in all kinds of weather is 12,000 feet, but ordinarily this time of year the pilots take more altitude and many

times keep their birds up to 16,000 feet.

This is a feat in itself and shows the power and construction of the Air Mail planes.

For the first time in the history of the Air Mail a ship was landed in the bosom of the thousand and one [xx]

has been in service for almost three years and this is the first time that a pilot and his ship have been forced to make the attempt to "set 'er down" in this area

that looks from the air like some hungry beast awaiting a victim.

When the scene below is viewed from the air there is a terror indescribable that assails the senses and makes the passenger draw down into the cockpit.

One is torn between the dangers and the beauty of the pictures along the top of the ranges, including the magnificent body of water, Lake Tahoe,

encompassed by high, jagged mountains and peaks, and timber-covered slopes.

Savage and as terrible as a mountain cloudburst came the first blasts of the cyclonic gales that rocked Ship 164 as Pilot Vance left the Marina field and headed up into

altitude for his run to Reno.

He tried the different altitudes.

He went slap into a 30-mile head wind as he drove the ship toward Sacramento.

When he reached Sacramento he was at 13,000 feet and against a 60 mile wind.

On he struggled, the new motor whining its song in defiance.

The time was one hour from take-off at Marina - just double time for the run in ordinary flying weather.

Still, Vance, taking advantage of the different altitudes, thought he would make the Hump in some one of the levels where the hurricane had abated somewhat.

Over Placerville at 13,000 feet he met the full force of the wind-swept spaces.

Ninety miles it registered.

His speed against the wind tide dwindled down to 20 miles an hour.

He knew that his new motor was consuming nearly thirty gallons of gas an hour.

The minutes were climbing up into tens, twenties and into half hours, and that's some consumption in the flying manual.

He would stand still for a minute or two and then when there was a mite of a let-up the motor would bang away at maximum and the propellor

would whirl in a halot at nearly 1600 revolutions a minute.

He reached Colfax, that pocket hellhole that is always rough sailing, even in fair weather.

His speed was reduced to 15 miles an hour.

The motor labored, the profellor bit into the oncoming gale.

The wires howled in frenzied accompaniment to the screeching, whistling forces of the rushing winds - winds that seemed to be preparing their victim for the

sacrifice to their gods, the elements.

Now he had almost reached the Hump, up there where the American river and the hundred and one little streams that go to make the great river have their birth and

start westward.

He was just on the slopes of the moluntains and the piled terrain, with masked death down there underneath.

His altitude was 13,000.

In the space of time that it takes to look from one instrument to another as overhead down current crashed against the top of the ship and it was

pressed down to 9000 in split seconds.

Then as the pilot made [xx] certain destruction his altimeter showed that he was rising with the same terrific velocity that smacked him down.

And saw his speed was only between 15 and 20 miles an hour.

Three times this never-before-heard-of rise and fall obtained.

During all this time the winds, coming broadside in angry impact, threatened to break the fusilage in two, now one side, now another.

And at the same time the typhoon hammered on the ship's nose.

At last he gained a point over the Hump.

The day was bright and beautiful.

Reno could be seen in the far distance.

All the thousands of the earth's beauties unfolded before him.

He was over the great snow fields, in another world from that of the green of the fields in far perspective.

Over a white world he almost hung stationary, his gaze noting the far northern icebergs and their towering, scintillating prismatic beauty.

All this Vance saw as he struggled for life.

Then with an additional splurge the wind backed him down and back westward from the Hump.

His extraordinary initiative, his natural superlative knowledge of the feel of the ship and his courage took him again over the Hump.

Now he had fought for three long hours, a lifetime of danger, with death lurking for any false move he might make.

He was over the Hump at 5:40 p.m.

The stunning, racking fact was born back to him that the gas supply was just about exhausted.

Sputter, sputter, and with a cough the motor went dead.

The gas supply had been used to the last drop.

Then the game little pilot turned in the "gravity" - the fifteen-minute reserve that is carried on the ships.

Ahead was death in the dark spots and little back spines that protruded from out the glare of the ice fields.

Over to his left was, as he had remembered, a small natural snow lake that had been dammed artifically as a water reserve.

He nosed the silved beauty for that spot as near as he could make out the circle that denoted the little pond.

He was not positive.

It was just the intuition of the airman.

Then he noted the little telegraph office that he had marked from the air many times as a point to be remembered in event he was lucky enough

to make the ground in emergency.

Down like a bird that had folded its wings he came with momentum as swift as light.

Leveling off, he touched the ice field that covered the little pond.

The great ship remained level.

Then he "set 'er down" and along upon the crust of ice that cover the 14 feet of snow the big ship glided.

Then a soft spot turned it to one side.

The intrepid flying man was still at the controls, watching, waiting, hoping.

The plane began to settle.

He thought that he had laid her down fair.

But just as she was about to stop one of the wheels struck a soft spot and then the other landing wheel did the same and up went the tail of the ship until it stoo almost vertical,

with propellor and nose buried down in the snow through the heavy crust.

Vance alighted just 200 yards from the little telegraph station where two young women were stationed.

He dragged his mail to the flag stop.

THen he went back to ship ship and looked it over, expecting, of course, that there would be a damage that would mean that his pride bird would have to be all overhauled.

He dug about the propellor and went all over the plane.

There was not a thing found to have been damaged, showing that his master hand at negotiating his ship had saved it from destruction.

There was not even a scratch upon the beautiful bird.

He knew that his motor would be useless, of course.

There was no way to save that.

It would be frozen up long before the Motor Macks would reach it and dismantle and ship it to its home hangar at San Francisco.

"It was the very worst experience I have ever had in the five years that I have been flying," said Pilot Vance when he arrived at Soda Springs at 9:30 in the evening.

"I have come near the final washout once before.

I have had many a struggle with the winds, with stalled motors, with other accidents to the ships I have flown.

But never before was I called upon to such exertion, to such steady application to every control as I was on this trip.

It was, indeed, the peak of every fight I have had to save my life."

Vance was a tired, worn-looking young chap when he alighted from the Overland Limited.

His face was still drawn and showed gray under the tan of the winds and weather.

His movements were indicative of a lassitude of terrible strain.

But Vance told his story:

"On February 2, 1923, Harry W. Huking came into the office at Frisco field.

He was telling Superintedent LaFollette that he had had a strange experience with the winds between Colfax and the Hump.

When he finished his story I was rather skeptical.

He said that he was driving into the gal head-on at 13,000 feet, when suddenly his ship was dropped to 9000 in time that could not be reckoned.

He went on to tell that he was carried up again almost instantly to the level he had left.

Again and again he was pushed down and then slammed up with a speed that was almost breathless.

This was new to us all.

None of us had even been through anything like this.

Then at the same time the winds came at him cross-wise and with such force that he imagined the smashing of the winds against the fuselage would press it into smithereens.

At the same time the gale was crashing and moaning against the nose of the ship.

The wind came with untold velocity from three different directions and apparently with the same awful [xx].

[Pilot Claire K. Vance]:

"This was the day that Huking was in the air for three hours and seven minutes fighting the hurricanes.

Well, I had almost forgotten that.

But, Lordy, how it was brought home to me when I had this same uncanny experience and in the identical place.

"I felt the Frisco (Marina) field at 2:20 p. m.

I had a new motor - a smooth-running, wonderful engine.

I was supplied with plenty of gas, 100 gallons.

Everything was just fine, and Boggs, who had tested out the new motor, said it was a beauty.

I took right up into the altitudes from the field.

I leveled her off at 11,000 and struck a fine lot of wind from the east.

I paid no attention to the 30-mile wind.

I held the ship there.

"When I was over Sacramento the windage increased.

It arose up to 60 miles an hour.

I then tried the different altitudes up to 14,000 feet.

The same condition was through it all.

I came down again to 13,000 and headed for the Hump.

The day was perfectly beautiful.

The air was clear as crystal, and the visibility was above normal in every direction.

I was able to see ranges and peaks that had never before come into the view from any elevation before.

"Over Colfax I received the first warning of what might be expected.

The wind increased until it reached better than 90 miles an hour.

It was steady - steady as could be.

All at once in that minute space of time not to be reckoned the ship ran into an extra heavy bump.

Believe me, it jarred me and strained the belts.

Then another bump, but not quite so hard.

Then down she went, a sheer drop, a few hundred feet, and stopped just like landing from the air kerplunk.

"Gee, but that was a hard bump.

I then looked at the altimeter and saw that I had dropped from 13,000 down to 9000.

While I was looking at the altimeter it began to rise and went up with a flash back to 13,000 feet.

I was struck on one side by a blast that made me think that she would capsize, although the hurricane was hitting me square on the nose.

My speed was reduced to about 20 miles an hour.

Three times I experienced the feeling of going down like a plummet and then rising with the same incalculable speed, and always within 13,000 and 9000.

It was then that the unheard-of battle that Pilot Huking had came to my mind.

He was right.

Never before had such a thing occurred that there is any record of, here in this country or anywhere else.

"What was the cause?

The only reason we can give is that the gales had generated far, far away to north and south and from the east, and that the north and south

blasts converged in the holes coming through the thousands of miles of valleys that merge in that pot hole between Colfax and the Hump.

"Below were the snow-covered rocks, trees and canyons.

It is very difficult to pick out the little snow ponds and lake when all is covered with a foot ice crust.

Everything looks about the same in the great sweeps of glistening snow-packed country.

I had to make a landing.

Just as she was gliding and with tremendous speed I noted the little shack where Soda Springs is situated along the snow sheds.

"I made a fine landing, but fear was in my heart that I would soon crash against some obstacle.

Then one wheel of the landing gear dropped through the snow crust, then the other.

The propellor disappeared, and the 164 raised her tail and stood absolutely verical.

I almost bumped my face against the windshield.

"The two young women at the telegraph station, Soda Springs, were outside waving their hands.

That was the most cheerful sight that has greeted me in all my life - human habitation and real humans in that world of sparkling white fields under the hurricane."

[xx] at Reno field, met Vance at the depot on arrival of the Overland Limited that carried him and his mail.

In a few terse sentences Vance outlined the position of the ship and where it could be dismantled for shipment.

Caldwell was acting manager of the field in the absence of Major Tomlinson.

Caldwell called Motor Macks Johnson, Bogard and Case.

THey went to the field to assemble their kits and equip themselves with snowshoes.

They took the westbound Overland Limited at 4:30 a. m. and went to Soda Springs and, dismantling the ship, had it ready to ship to its home hangar at Frisco the next day.

(Copyright 1923 by Jack Bell)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen