How Huking Was Lost, Unable to Land His Ship Owing to Blanket of Mist Over Landscape

On January 20 Harry W. Huking zoomed up through a heavy ground fog from the San Francisco field.

He carried a big consignment of mail.

He drummed through thick, impenetrable density skyward and still skyward.

The moisture poured in streams from off the wings and spattered and spat against the cockpit windshield.

The force of the whirling, speeding air bird caused the water to strike the face of the pilot with such force that the exposed parts were raw and cracked.

On up into the vastness of the desert of clouds he drove his machine.

Then at an altitude of 17,000 feet above the earth he came into the sunshine.

Leveling off his ship on even keel, he started in the general direction of the instinctive, automatic line that leads towards the "Hump."

The bright sun danced over the mountainous billows in the vast sea of cloudland.

As far as the eye could reach the rolling, tempestuous combers, dark in the undertow, bright and with rainbow coloring, spread out everywhere.

From the winds below there would suddenly appear a mountain of clouds rising far above the tossing, moving ocean.

The mists would leave their spray, and innumerable rainbows would become visible for fractions of time.

Then from out the murk of clouds a sharp spire loomed up through the fog banks, then another, then a round top, now a jagged, shattered peak.

He had reached the "Hump" cross-over.

It was with a feeling of mighty relief that he picked out a wee bit of Donner lake, the lake that lies in the lap of the "Hump."

Down he nosed his ship until he reached 12,000 feet. Then he headed in the general direction of Reno field.

On he sped, over the shattered field of mists, only to find that there was the deadly ground fog covering the entire basin of the Truckee meadows.

The fog was thick, too thick to take the chance of coming down lower than 8000 feet.

The field could not be located, of course.

He made directly over the field.

The entire personnel hurried out to the field to watch the landing.

Darkness was approaching and the atmosphere was becoming denser with the night's coming.

Around and around the field he circled.

There was no earthly chance to make a landing and no use taking the chance of losing height and then get so low that there might be some difficulty

in "giving her the gun" to make altitude again.

The deception of the ground is the most dangerous thing to fool with through fog.

Around and around he flew, knowing beyond doubt that he was near his goal.

Down on the field the personnel once saw the ghostly outlines of the great ship high up in the mists.

It passed in a flash.

That was the only time that the ship was sighted.

Major Tomlinson hurried every available man onto the landing field, and flares were lighted with the hope that the dull, sputtering, wavering red splotches

could be seen by the pilot aloft.

Around he circled.

The hum of [xx] it departed into the distance, and then all was still, born of the falling of night over all the earth.

This was after 5 o'clock.

Nothing was heard of the pilot or his ship all that long night.

The last seen of him he was headed in the general direction of north.

Chief Mechanic Caldwell with two mechanics tumbled in their automobile and started north, hoping against hope that Huking landed without crash.

Huking tried and tried for an opening to land his ship.

On, on north he sped.

Then he dropped down to a lower level, hanging over the side an far as he could to try to locate a spot to "set her down."

Then the god of luck appeared for a moment.

There was an opening in the half light off the toe of Peavine mountain - and lo and behold, he saw the same long

parallelogram clearing that had been his [xx] when he was lost in the blinding snow of just days before.

That wonderful strip of closing and opening visibility at the northern point of Peavine mountain was his salvation.

This is where Silver lake is situated, just 15 miles from Reno.

Again he set down a short mile from the ranch of Carl Barnes.

He landed on the shores of the lake.

The ship was covered with adobe mud as though it had been painted with it.

But Huking was safe and unhurt and the plane was not even damaged.

Huking then started to the highway, that is, in that general direction.

He wanted to get in touch with Reno field and get his mail in.

He ran into the car containing Chief Mechanic Caldwell and his two friends, the mechanics.

They started to locate the ship.

The fog came down to the ground.

They hunted and hunted until 4 o'clock in the morning, and no ship did they find.

Then they went to the ranch house of Barnes.

Mrs. Barnes gave them all a satisfying "feed" for which they were thankful and for which nothing but thanks could pay.

They were tired out.

For 10 hours they had tramped the desert in search of the ship.

Their every thought was to get mail to the train so as not to default.

But they did default by the margin of ten minutes.

The ship was found when the fog raised at 9 a. m., too late to get the Fast Mail at Reno, although they raced as they never raced before.

At 4 p. m. Sunday afternoon Huking, still without rest or food, was taken out to the ship.

He flew it back to the field and arrived there in a few minutes.

An incident worth relating is the fact that when Huking landed and headed for the highway the little haby, 5-year-old Bill, son of the Barnes', ran

down to the ship and looked it all over and then ran back to the house and told his parents,

"The [xx] of [xx] folks to the flyer and the mechanics will be for always a special mark of gratitude on the part of the Air Mail.

Pilot Claire K. Vance also had a fog experience that will live in his memory. flying in a virtual tunnel of rock through the mists.

On January 19, 1923, Vance shot his ship straight up from the San Francisco field until he had reached 16,000 feet to cut through the fog bank.

All the way up the valley of the Sacramento he held this attitude - there was no way out.

He was, in fact, in another world - a world of dark banks and rolls and billows of clouds, white and edged red clouds, in rolling seas for distance unknown and

without measure.

He had been transported into realms of deserts and valleys and hills of moving mists of density that vision could not penetrate below.

Then all at once he was enveloped with fog - fog above, below, behind and in front of him.

The surf-like rolling would go over him in mountainous swells, leaving him and his ship a drenched, water-covered spot in the unknown of the high aloft.

Then the sun made a thin slash across the oceans of moving vapors, and he dropped his ship down into that ray as fast as his wonder plane could nose down.

He had been lost ever since he left San Francisco.

Now there appeared the outlines of Donner lake - impressions made upon the brains of the flying men as a recorded cylinder upon a phonograph.

He knew where he was, and lower and lower he took his ship.

Gliding down and above Truckee, he made his way under the miles of clouds and mists above him.

His altimeter read 50 feet above the earth.

From Truckee down to Verdi is the narrow canyon of this famous river.

It cuts through a gorge like the Royal Gorge of Colorado.

Ragged, jagged granite and porphyry border tho narrow canyon.

The distance from Truckee to Verdi is 25 miles.

There is not a single place within the confines of this passageway where it would be possible for two planes to pass without a collision.

Without doubt this stretch of canyon is equally as difficult to negotiate as was the thrilling experience of Blanchfield through Palisade canyon to the east when

the latter made his hair-raising ride through a blizzard over the tops of the telegraph poles.

It takea a superman to even make the attempt to fly through the dangers of confines where death lurks every second.

The greatest danger, of course, is the gales that generate in the broad sweeps of country above and come whistling down through narrow box canyons and spend

their energy against the walls of narrow, rock-bound outlets.

Vance would come within inches of the points along the winding, twisting route - the snake-like turns, then the sharp angles and then again into the double "S's" of this chasm.

Time and time again the tips of the wings of the speeding, roaring ship would actually scrape the sides.

The pilot would have his head from one side of the

ship to tha other, darting a look [xx] as the Silver King would battle with the swirls of wind as they screeched through the rigging.

There was a slight haze in the canyon.

Reckless?

NO!

American nerve.

Vance followed that railroad like a hound follows the scent of a rabbit - it was his one chance to save himself and his ship, and his pride in his ship is like the pride

any man has in his most prized possession.

On he came, tilting his ship in side slips and then over and side-slipping it opposite to graze the great rough formations about him.

All the way to Reno he flew over the railroad, never 1eaving the point of vantage above the shining rails.

Then dusk began to fall and the fog began to settle down to a ground fog - the most feared condition to contend with in flying.

[xx] nothing but the glistening rails 40 feet under him.

Before he realized his position the lights of the main streets of Reno showed in faint rays through the fast-falling darkness.

He headed her up and got his direction of the field from familiarity of the streets and tangent - he went for the field.

The personnel at the field had departed for home.

There had been some discussion about the ship coming through.

When the heavy ground fog began to hide nearby objects on the landing field and darkness was settling they departed for homes two and a half miles away.

Then just as blackness was settling and the ghostly lights of the hangar showed dim through the windows, Guards and Helpers Connor and Robear heard the approaching ship.

They grabbed the red flares and made for the field runway.

Connor had just emerged from the office with a lighted flare in his hand when Vance, scarcely off the ground, came in with such lightning speed that the

watchman had no chance to make the field.

It's better told by Connor:

"I heard that ship coming and knew the boy would have a mighty hard time making out the runway to land.

I had just turned out from the corner of the office when he came seemingly right at the office.

1 dropped the flare and took to my heels, thinking that that was the last of the office and the pilot - his speed was terrific and the roar of that motor sounded

like a million thunders.

I took to my heels and headed for the tall uncut - never so scared in my life when that ship appeared as if by magic right in line and headed directly for me.

Say, I didn't get over that for a week.

"No, sir, I will never forget how Vance came in from out of that fog and darkness as long as I live.

How the dickens that boy ever made out the field is more than I can figure out.

Those boys with Blanchfield and the others are wonders.

As a matter of fact, Vance touched the tops of trees all the way out to the field and barely missed flagpoles and many buildings - a feat that has been done but seldom at this terminal.

The crux of every flight made is the care, attention and personal feeling and labor put upon the ships and the great motor, the careful servicing.

This is the seed that makes the rest of the vast plant grow and have its being.

Added to this that feeling of knowing that all that is humanely possible has been done for the safety of the pilot when he takes his ship into the air

is the outstanding factor of success of that very same flyer.

If there was a little doubt in the mind of that pilot that his ship had been neglected in the least bit he would naturally be worried.

This would of course retard his performance in his line of duty.

But there is nothing but that absolutely trustful understanding among the entire personnel along the western divisions, and of course the same conditions must

prevail all along the transcontinental air road.

The craftsmanship of the "Motor Macks" on Reno field and San Francisco field has proved to the world that the technical knowledge and genius of workmanship are there.

They have invoked official Washington recognition of the master care of motors and the perfect construction of the standard De Haviland B-4 type of ship used by the air mail.

To Reno is presented the magnificent compliment of being perfect in efficiency of its personnel, under the direction of Major O. A. Tomlinson, field manager, and

his incomparable assistants.

San Francisco is [xx] the supervision of Assistant Superintendent LaFollette and his expert array of "Motor Macks."

The staffs at Keno and Marina fields are justly proud of this distinction, of the road sweeping appreciation of their careful labor and inspection of the world-famous

ships that fly over the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Major Tomlinson has received official notification from the Postmaster General at Washington that the United States air mail was the recipient of the

Collier aeronautical trophy.

This prized award is the most sought of all the cups and rewards given to every branch of aeronautics in the United States.

It means that the United States air mail has the recognized unbeatable aggregation of experts with resultant accomplishment in this country.

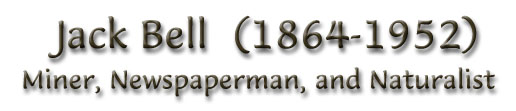

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen