Vicious Lizard Moves Faster Than Sidewinder,

Stands Stiff Legged Defying Man, Dodging Bullets and Rocks

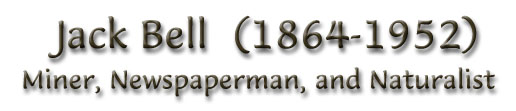

By Jack Bell

GILAS and lizards are sure in a class by themselves.

They certainly startle a man down there in the vast waste sands and petrified forest in New Mexico.

Some of them seem to have sense, and others are fighting, untamable vermonts.

They are of every length, from a few inches up to twenty inches.

Some are slim, some are plump - some are all tail, others like the gila monster have a stubby - as a matter of fact, scarcely any tail at all - just a stump of an appendage.

Poisonous?

Well, now, there are many of them mighty hard to catch.

There is one down there that the naturalist seems to have overlooked.

Whether this species is venomous or not I have no means of knowing.

He is the only one that I am a bit afraid of.

I'll tell you about him.

Better tell you what he does and then you can form your own conclusions.

Oh, yes, there is even a greater area of petrified forest in New Mexico than the much advertised one over in Arizona.

A heap more interesting too, from every viewpoint, and standpoint.

Well, many times I have been making my packs ready to throw on the burros when I would chance to look in front - invariably in front, and there would be a lizard, anywhere

from ten to sixteen inches in length.

He is of a light greenish color, and seems to have banded stripes of a lighter color about the heavy part of his body.

His head is the identical shape of the long slender spear head of obsidian, also found down there.

Well, he will raise stiff legged just like a tarantula, when the latter is mad, and lash his tail for all the world like a domestic cat.

His mouth is half open and his dark and forked tongue darts back and forth like the feeler of a bull snake.

Make a move toward him and he will advance to attack.

Of course, a man naturally gives ground at this unexpected attitude.

He will come almost within striking distance.

He is sure a very undesirable looking reptile.

His head is smooth, his coat is as smooth as any of the snake family, his movements are even more rapid than the sidewinder.

As a matter of fact, the eye can scarcely follow his sudden darting here and there as he retires and advances.

His manner is rather uncanny, his purpose I could never solve.

The inside of his mouth, when he stands on the defensive greatly resembles the gila monster, with the one exception that it is flesh colored.

I have tried every way that I could conceive of to get a specimen of this fellow.

I have taken snap shot with the 45 Colts, with a heavy rifle - thrown rocks and chunks of wood at him - well, everything but a shot gun, and I have never been able to score a hit.

He is not there when the shot or missile is fired and that's all there is to it.

Then if you start after him with a long stick, like a jointed fishing rod, he is always just out of reach; when you strike at him, he has moved to one side or the other, and back

he comes for the attack just like a flash, but always just out of striking distance.

I have fooled with them half an hour at a time.

Then all at once he will raise up stiff legged, switch his long tail a few times, and in the wink of an eye, disappear into the sane dunes, or in the petrified rocks.

Some day I will take a shot gun and get one of these fellows.

Probably a cousin of the gila monster.

This fighting rascal is not plentiful, but I have never failed to see them when I was in the heart of the desert.

The gila monster!

He is the most repulsive of all the snake and all the reptile family.

Even worse than the stinking moccasin of the southern swamps.

The gila is about the most sickening thing on the desert, if he is disturbed after he has been lying in hiding,

gorged, the effluvium that comes from his decaying food is dead sickening.

I have found that this is what he depends upon for protection and nothing but a road runner will take a chance with him when he is in this condition.

The road runner will never molest either the small gila monster and the rattler family unless it is with the sense of protection.

I have never seen the road runner attack them unless they were within easy reach of their nests in the chapparel.

Then he will do battle and will always win.

Of course the road runner feeds upon the smaller lizards, tarantulas and centipedes.

But the freak stories of how a road runner will build castil about the coiled rattler, and then jump into the ring and give battle is the mere arrant nonsense.

Then again right here - the prevalent belief is that a snake will not cross a hair rope, riata, lasso - all rot, simply all rot.

The rattler will go anywhere - and he will also crawl up into a cat's claw bunch of growth, where a man would of necessity have to use gloves.

But about the Gila.

Take it upon a hot day on the desert, and along the upper reaches of the Gila river, out on the mesas, in the malapi one will always find plenty of them of all

sizes and in all conditions.

When he is out after his feed I have always found that his movements are the same as the rest of the lizard family, that is rapid of movement, and only when he is gorged with food is he

the loggy, slow, disgusting thing.

He is universally regarded as the slowest thing on the desert.

Get to fooling with an 18-inch one on a hot day when he is out after feed and you will soon be

convinced that he is dangerous to take chances with on the idea of loggishness and slowness.

Right here I want to disabuse your minds of the fact that the gila can kill a human, or anything else with his "breath."

This one of the chosen and believed traits and powers of the gila monster.

Rot, simply rot.

He exudes the gas from his decaying fill of feed, that's the poison - it is sickening.

But even down there in his own environment he is believed to have this power.

His bite is just as deadly as the rattlesnakes of the desert.

His venom will analyze about the same.

He will bite upon any and all provcations.

When the venom is ejected from his fangs it is a beautiful light purple.

Then as the air attacks the poison it turns black, making the very same reaction in human flesh as the rattlesnake's.

He is dormant when filled and lively on the hunt for food when hungry.

Some years ago I was crossing over to the Gila river valley from the San Simon valley.

Making camp at a seepage about half way, there was a Mexican and his family of several little ones at the same "spring."

There had been an eighteen months' drougth, and the rains had started about six weeks before I made this country.

As far as the eye could reach in every direction the hills and valleys were covered with the "butter ball," the California yellow poppy.

Pea vine grew in every cranny and nook of the heretofore bare mesas and hills and mountains.

In some places it stood four feet high.

It is one of the most nutritious and fattening of all the forage plants.

Where I had set up the small tent was removed from the Mexicans some hundred feet.

Below their camp was a little rough, box canyon, only about 75 feet long.

It was very rugged.

Probably no one was ever in it until this time.

One of the little Mexican girls, a tot of 7 years of age, let out a scream at about noontide.

I rushed down with a hyperdemic syringe filled with a solution of permangante of potash - thinking the child had been struck by either a rattler or a gila monster.

I found the child standing beside the skeleton of what had been a fair-sized man.

The bones were bleached and dull white, the torso section and skull was there, but the rest had been packed away by animals.

The child was not frightened by the discovery of the human body, but at the half reared gila monster that stood in the narrow trail before her, shutting her in against

the back of the box canyon.

I lifted the child out of danger, and rigged up a snare and brought the gila out of the pea vine and rocks.

He was a lively one, too.

This was the largest specimen that I have ever seen or heard of.

He was twenty-two inches long and thirteen inches around the heavy part of his body.

He was hungry, and was willing to take a chance at anything.

He was a fighter.

I went back to where the skeleton was to examine it.

I killed three smaller gilas right there.

Sticking between the ribs on the left side of the skeleton was a stockman's knofe.

One of the strong two-bladed kind used by them alone for ear marking, picking brands and as a general knife in the cow business.

The point was broken, the open blade was in a good state of preservation - the one that was closed was almost rusted away.

I still have the knife.

It spelled some unknown tragedy of the great desert.

I reported the matter to some of the old timers at ranches down in the valley, but nothing was known of the disappearance of any inhabitant there.

I had buried the bones where I found them - not even a button left as a mark of identification. Of course it was murder - red murder.

There are any number of lizards - gray, green, mottled brown, yellow striped, white striped, reddish, brown, and one little fellow, that has a scarlet ring around his neck.

There is one that is called the "swift" by the prospector.

He is a light mottled gray, and has a white ring around his neck.

He never grows to exceed ten inches in length.

He is very easily domesticated.

He invariably comes to a fire for flies that eternally show about the grub box.

He will come inside the tent and begin catching that pest, the blowfly.

It is a treat to watch him in every cortortion imaginable taking the flies.

When he has his fill he will lie upon some of the camp equipment and snooze away for a couple of hours - then he is voraciously hungry again and goes after the glies with

an added feraciousness.

If the camp is made for a couple of days it is not unusual to have a half dozen of them running about the tent.

Then one can pick them up and stroke their heads, and they seem loath to be put down on the ground again.

They will remain in the tent until camp is broken.

Everywhere on the big open

Continuation of Article

desert sand basins one will find all varieties of the lizard family.

There is a little brown one that never attains a growth of more than five inches.

He is merely a darter.

I never yet have been able to get my hands on one of these.

They are exceedingly timid, and disappear in the and dunes with slight of hand quickness.

Flies, and where they come from in the great miles of sandy desert?

Goodness, don't ask me.

All I know is that the house fly and the blow fly appear any place in the desert and mountain peaks alike, just the minute camp is made.

There is no place on earth where flies are so plentiful as in the uninhabited places of our almost unknown desert fastness.

The only lizards that are really friendly are the ones mentioned above, and the 10-inch beauty that is marked with orange and mottled in grays and browns,

with a silver lining.

They come about the camp but will not feed on the vermin like the white ringed species.

But they will go about camp and show no fear at all when picked up and petted.

On a friendly basis with these two varieties of desert lizard in the great basin is the horned toad.

These small reptiles of the silurian age are really pets.

They soon learn to be a guardian of the chuck box, and to vie with the lizards in keeping the flies away from it.

Many prospectors will carry two or three of them along for strictly sanitary reasons.

He guards that grub box like a soldier.

When a fly alights near it he is after him like a flash.

When packed along they show a rapid advance in growth.

I have seen horned toads in a prospector's outfit that would be as large around the shell as the ordinary saucer - and the spikes on the head would look most formidable.

They are never lazy - right there on shift day and night.

One of the amusing things of both the toad and lizards is to watch them when they race and chase each other.

Like lightning they will change direction; the powerful tails of the lizard turning sharp angles very often upset them and they will turn over a couple of times.

They will keep up this play for many minutes at a time.

This applies to all of the lizards in the big places.

Take the lizards, snakes and quail; yes, the gamble partridge- "cotton top" of the prospector is found in the desert wastes.

They seem to get all the feed they need about the rocks, and about the scattered bunches of cat's claw.

All sorts of small feed, and they also eat the leaves of this brush.

But as I started to say, the animals as well as the reptiles along roads of travel, and even along the edges of the big deserts are altogether different from the same species away

out from the lines of travel.

The little bit of civilization makes all the difference in the world.

Habits, feed and environment all seem to make a change in them all.

The lizards and other life in the great barren deserts of the United States are the most interesting, as well as the least known of all life on the continent.

This is the country of 50-mile wide water jumps, and the hardest trails known to the prospector and burro alike.

It's the country where very few prospectors travel.

It's the country where one may find opals, turquoise, borax, soda, potash salts, oil and rock writings of the centuries agone.

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen