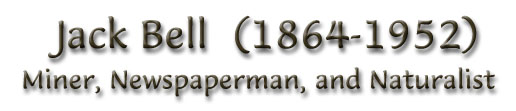

By Jack Bell

Air Mail Ship Is Covered With Down, Plumage, Blood After Blasting Its Way Through Ducks

Pilot Johnson Finds Himself Faced by Wall of Living Birds, Forced to Puncture Way Through

IF you were an Air Mail pilot, how would you like to find yourself suddenly up against a wall in the sky?

Particularly if that wall were a living wall, black, solid, vibrating!

And your only escape were to punch a hole through that wall and get your ship out into the clear sky again.

Just that contingency has faced pilots of the U. S. Air Mail on the San Francisco-Reno line.

To the men who fly the mail across the mountains and deserts there are compensations to break the monotony of level straight and gently swaying riding.

These men are keen for somethint out of the ordinary.

Maybe they weave strange scenes from the flights of birds against a background of puff ball mist in the heavens,

or take and make for themselves pictures weaving together the wonderful coloring of clouds, with the shades and startlingly

beautiful nature paintings that lay against the great mountain ranges in the distance.

As spring approaches comes the flights of myriads of birds and water fowl.

They almost darken the sky.

They shut out the sun at times.

It is the migration north to nesting and breeding grounds.

Nevada is the sanctuary and largest breeding ground for the unattraction pelican.

Tens of thousands come from out the winter homes from somewhere and wend their way to this island in the almost [xx] in Pyramid Lake, Nevada.

They are in flight.

The great pelican looks like a miniature airship when gliding.

He has a monstrous wing spread.

One great band has already arrived at the summer home at Pyramid Lake, that wonderful body of fresh water that covers 43 miles in length and 20 miles broad.

Along the more shallow shores are millions of [xx] used for bait for the game fish.

When flying low along the bare timberless mountain peaks as they cross the Hump, there are times when coveys of ptarmigan with swift flight make for safety into the edges of the rock slides,

where they can lie safe from the terrible monster that roars above them and across their feeding grounds.

Time and again the airman must use every trick at his command to escape ramming into the great flights of water fowl that fairly darken the sky in the spring and fall migrations.

It is very ordinary for great clouds of these birds to cover miles of sky expanse.

Were the pilot unable to judge quickly the straight and frightened cross flights of these myriads of water fowl, and if one single bird, even the very smallest, were to be

struck by the tip of the whirring halo-like propeller, the "prop" would be splintered into broom-like condition and be as useless as if there was no motive power.

The plane would become a gliding dangerous proposition.

However, a fowl has been known to strike near the hub of the propeller, tearing the bird into a puff of feathers and down, and scattering the blood and minute bones over the blade and over the

radiator front as well as sprinkling the silver wings with the red stains.

There are but two circumstances where the Hump fliers have been forced to run smack into the great spread of living birds.

Eugene Johnson, now an Eastern pilot on the Red Line air road, had an experience that was anything but pleasant.

In fact, he was in a perilous situation and surroundings over which all his initiative had no control.

His beautiful ship came down into Reno field camouflaged with down, feathers and parts of water birds.

The great plane was unrecognizable - a ship of mystery - when coming in above the field at Reno.

It is a most difficult matter to negotiate through the great flocks.

The leaders may make straight for the nose of the speeding ship.

They change direction suddenly under fright and scatter like a band of cattle before a motorist on the highway.

No indication is ever given as to what direction they take.

Generally the birds of transition make straightway for the ship, and the pilot is forced to dive, to zoom, bank and do other stunts to get away from the danger.

The most perilous places are along San Francisco bay and out in the neck of Sulsun, the resting place and sanctuary of the water birds.

Then when they cross over the saddle of the hump, the direct tangent for their flights north and south, there is an ever-present danger

to the flying men during the seasons of movement.

In March, 1922, Pilot Eugene Johnson took off at San Francisco field with a fog that lay but twenty feet over the waters of the bay.

There was no earthly chance to get out of the rolling mists.

His skill stood him in good stead, dodging the ferryboats, steamers and smaller craft as he zig-zagged his perilous way over the incoming tide.

Gulls screamed and passed between the wings, geese honked and scattered up into the fog as the terrible, deafening drumming Liberty tore through the space between

water and ground fog.

On he swept, a bird of giant, terrible appearance.

Here he would barely miss the masts of a ship, there almost against the sides of a liner.

There is a nerve-racking thudding, resounding roar that is one of the most painful experiences to be encountered - flying under the density where the sound is so closely confined and so

multiplied.

After getting as closely to the shore line as safety permitted Johnson noted points along the beaches that indicated that he would soon be well towards Suisan bay.

The clouds began to lift a trifle, and there seemed to be a ceiling of about 30 feet.

Now the millions of water fowl began to move, as the thunder of the approaching ship tore through the edges of the heavy fog, throwing back eddies and rolling, tumbling mists, as the pilot swept on.

Now the great worlds of ducks, geese and [xx] began milling.

There was not a space that was not literally alive with the frightened fowl.

Johnson did not have a chance to go around the myriads and countless thousands.

He tried.

He wasted many valuable minutes in his endeavor to find an outlet without crashing into the clouds of water fowl.

He even turned his ship.

"It was ducks to the right of him, ducks to the left of him, and ducks in front and behind him."

Johnson was perfectly familiar with the danger of having the very tiniest obstruction strike the tip of his propeller.

He knew that it would mean a dive into the bay.

He throttled down.

He "gave her the gun."

He tried every which ay, even to taking his ship up into the deadly [xx] him even to make out his ship's wings, and the long spurts of flame that came from the exhausts

merely added to the fright and confusion of the ducks.

He was up against it.

He was now within striking distance of the shores at the narrow point of Suisun bay.

He took the thousandth chance and slammed his ship with open throttle into the mass of water birds.

Squak! bang! they slammed aginst the wing wires and the feathers and blood of the hundreds of ducks made splotches and streaks over wings and along the sides of the fuselage.

He came into the edges of the bay.

The lights began to show through the thinning and rising fog.

Then out of the gloom and danger zone the great silver king headed up and up into the altitudes.

Luck was with Johnson.

The water fowl had been torn into at a speed of 120 miles per hour.

There was not a square foot of the ship that did not show either feathers, down, or blood.

The wires of the ship were fairly ropes of white and brown.

The blood had spattered the wings, wires and edges of the entire ship, and control wires leading to the tail of the ship.

Every part of the ship's gear on her tail was marked with the part or parts of the ducks that had been on the trail of the air monster.

[xx] field - yes, long before it landed - the personnel gathered and what wonder on thier faces and exclamations of voices gazed in rapt surprise

at the unusual sight of a decorated ship - a ship that looked for all the world as thought it had been beautified by a master hand.

Johnson's hood and goggles were fuzzy, there were feathers and down in the cockpit, and on the fur neckband of his flying suit.

Pilot Johnson 'set her down' with that skill for which he is noted.

The crowd of Motor Macks and several visitors hurried out to find the reason for the unusual dress of the silver wing beauty.

There it was, not so beautiful near at hand.

The wires were like ropes, parts of carcasses of water fowl hanging in almost every place where there could be

an anchorage for a two-bit piece.

Streaks and gruesome red smears covered the beautiful wings, under and over.

On the hub of the propeller were tiny showings of down, and the blade with its scars of blood

reminded one of the terrible guillotine - and at once the thought came that the propeller was indeed an awful engine of destruction, whirring as it does with revolutions of 1600 per minute.

Many times the pilots of the Hump are called upon during the moving season of the emigrant water fowl to make far sorties to escape the great migration.

"It was a perilous situation for me and the ship alike," said Johnson when he stepped from his ship and walked around and about it.

[xx] that before and never will be if I can help it.

Through my goggles, she looked all dressed up like a South Sea Islander, but - gosh, it looked like she was getting ready to go to some great function, or all

dressed up for grand opera."

There was not a wire, not one bit of the 156 that did not show evidence of the smash into the great flock of wild fowl.

"I had a hard time getting off down below.

Never saw such a heavy ground fog.

I had just enough ceiling to remain above the water - just like a dipper flying along.

At first I was too busy dodging water craft-masts, ferry boats, motor launches, and even row boats, to think of anything else.

From the air we could all see the millions of wild ducks of every kind and every color, not to mention swan and geese.

"The little bays and estuaries were literally covered with them.

It is during mid-March that they congregate down there and over the small lakes and streams that actually follow the Red Line air road,

when they are assembling for their flights to nesting grounds in the North.

"The pilots of air craft all know and all have watched this migration.

But at no other place on the face of the earth is there such dense clouds of them as is found along the valleys and along the coast lines of San Francisco Bay.

When the movement starts we either try to go over or under them.

So far none of us have met with them high in the air.

"Right here while we are talking about these migrations I would like to know from someone who has the positive information what breed of water fowl has great speed

and flies up in the altitudes above 17,000 feet above sea level?

There are great flocks of these, and they fly like the wind, as fast, maybe faster, than a ship.

"Yes.

It was nip and tuck with me down there on the bay that March morning.

The mists began to lift when I was within a few minutes of the neck of Suisun bay.

It was here that the noise of the ship startled millions of fowl that were on the water.

They arose in mighty clouds, and so dense were the shadows they made between the uplifting clouds and billowing mists and the water and ceiling that all

about seemed to be suddenly overshadowed by falling storm clouds.

"I gave her the gun and headed out towards the lights that began to appear in the open away from the waters of the bay.

Even above the roar of the motor I seemed to hear the whistling air - cutting wings of the birds.

"They were on every side.

I was surrounded by this life in every particle of atmosphere for miles, it seemed to me.

I had just one out, and that was to take a chance and ram through and trust to Providence that a bird would not be struck by the propeller blade tip.

"Goodness only knows how long it took me to drive through that vast sea of feathered web-foots.

Believe me, it was long enough and the sweat broke out all over my body at the thought of the destruction I was forced to cause.

"The ship, at not over a 100 feet from the water, was making her maximum speed, about 120 miles per hour.

The propeller was doing its maximum of almost 1600 revolutions per minute.

There was nothing else to do but plow through them - absolutely no chance to miss the immense moving sea of water fowl.

"When I rammed into them there was plenty of bumps just like a rattle of bullets against a wall.

The air was a mass of feathers, dropping birds, and parts of the fowl passing by the cock pit like flashes.

It was certainly a scene I never want to see re-enacted."

"How long did it last?"

"It was probably [xx] though it seemed many minutes before I came out into the sunshine and saw the high blue above me.

Believe me, I zoomed her up and took to the high places as fast as the ship would make it - and the 156 is some climber too.

"All the way to Reno feathers and down kept blowing away from the ship.

Reminded me of a ground chase of fox and geese.

I felt mighty bad about it, as I am a lover of the whole bird family, and although it seemed like wanton destruction, I had absolutely no other chance

or recourse to get by them.

I took the only other chance a man could take."

(Copyright 1923 by Jack Bell)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen