Johnson Tramps Miles Through Snow to Find Railroad; Mail Lost

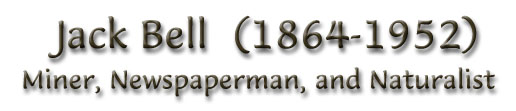

By Jack Bell

Another page has been written into the many thrilling experiences of the intrepid flyers of the United States air mail over the "hump."

To aviators throughout the entire world the stretch of country between Reno and Sacramento is known as the most dangerous flight, either commercial, military or air mail.

There are 100 miles of rugged country where it is impossible to set down a ship without a washout.

Yesterday morning Eugene C. Johnson took off from Concord at 8:45.

The weather was fair and clear when he reached Sacramento.

The hump seemed to be clear as he gained altitude.

He noticed the beginning of threatening clouds which generally presage a storm over the high Sierras.

Accustomed as all the flyers are, he thought nothing of this and took altitude.

When he reached the sloping of the high places of the hump the storm fell upon him, a snow so thick and intense that

it was impossible to see even the tips of his wings without turning his ship to an angle of 80 degrees.

STORM INCREASES

The storm increased and the wind velocity increased.

He began to lose altitude and tried to make out.

He was just about an hour out of Mather field when, with the increasing fall of snow, darkness almost enveloped the ship.

He circled, and circled, and circled, trying to make up or out.

Occasionally he would go by dark spots.

He tried to find it again circling.

But it was no use.

He was trying to make a landing and when he looked at his altimeter, found that he was too low to try a jump.

It was the first time that this famous flyer had ever been boxed without an out.

It was the first time in all of his 5,500 flying hours that he was unable to see a place where he could set down his ship.

Then he took the chance that all flyers do in cases of this sort, when there was absolutely no chance to get out of the pocket he was in,

completely lost but still with the subconscious knowledge that he must make down.

He felt that he might with one chance out of a thousand land his ship without a crash or washout.

He took that chance.

This occurred, as near as can be determined, at 10:25 yesterday morning.

GIVES OWN STORY

His own story of his complete washout follows:

"I left Concord on schedule at 8:45, expecting from the looks of the weather, to make a fine flight, good time, to the Reno field, for the

reason that I had a good strong tail wind.

It was just fine, even after I left Sacramento.

When I got up towards the rough part of the western slope of the high Sierras, heading for the hump, the storm settled upon me like a black shroud.

There was no ceiling in any direction.

In all my years of flight in bad weather I never experienced such a severe snowstorm.

It was more to my mind l8ike a veil that was clotted, and one could not see through.

I had followed the railroad track like we always do, and figured that I must be at least within walking distance.

When the storm hit me I tried to get out, tried to make the hump, tried altitude, circled lower, tried to make Sacramento and Mather field again, and as a matter of fact,

I tried with all my varied experience of flight to get out of his awful hole.

I am free to confess that I was frightened.

It is pretty darn lonely up there in a situation of this sort.

I made ready to jump, but saw that it would be dangerous on account of the loss of altitude.

I then began to circle.

I kept circling.

I would find white spots that looked like snow upon the ground or high up.

I could not figure whether it was rocks, trees, or the ground.

I would lose this point, then would try to find it by circling.

At last I took the chance that was all take.

I shut off the motor, nosed it over - then came the crash.

BADLY SHAKEN UP

"Well, I was badly shaken up, of course.

Back of me, against a cushion up through the fuselage, barely scraping the cushion where I rested my back,

stuck the stump of a freshly-broken 14-inch stick.

That was pretty close!

I sat in my seat, looked over the ship.

Her tail was standing ujp.

Every other part of the ship with the exception - and here is one of the freaks of flying - both the mailpit and my cockpit were not even cracked.

It was the most complete washout I think I have ever seen.

With merely a shock I had escaped death, or serious injury in any case.

When I looked about I saw that I was in a deep gulch.

It was still snowing and 40 inches had fallen, so they told me, from the time I had crashed until the time I reached the railroad track near Tamarack

four hours later.

"all our ships are equipped with webs, and of course we all carry hard rations.

I had an awful time getting the webs out of the wreckage.

As I stopped out of the cockpit I dropped into this fluffy snow right up to my chin.

It was the last of my favorite ship number 424, and that will be her graveyard, as she is beyond any repair.

There was nothing to do but to get out of there.

USED COMPASS

"I had my compass and I took out straight up the side of this gulch, that was, I know, at least 50 degrees, with eight or ten feet of snow.

I was packing my heavy flying coat, my haversack of rations, which was a load in itself.

I left my undercoat in the parachute.

My service coat, of course, I packed with me.

I had forgotten the old signals, but fired the magazine, two shots at intervals, which should have been three.

I never have suffered such hardships in my life as packing this heavy load and breaking trail.

I would take a rest occasionally under little spruce trees, where the snow seemed to be a little harder.

I would no sooner become relaxed than the wind would shake out the snow and completely cover me.

"At last I saw the long gash in the snow that indicated the railroad.

I dragged myself up to the great windrows that had been thrown out by the rotaries.

I had almost reached the top when the great bank gave away and I rolled back in a smother of snow.

After reaching the track in a state of almost absolute exhaustion, I started west, and soon reached the section

house at Tamarack and tried to engage in conversation a trackwalker who could not speak English.

In sigh language I at last made him understand that I wanted to telephone

and he directed me on west and I came to Troy, where later a special train sent out by the Southern Pacific picked me up and I reached Truckee and finished my

journey on the freight train into Reno.

After this experience one would think I was about done in, but I feel more like standing around chatting than anything else and

expect to fly my run to San Francisco in the morning."

CRACK FLYERS OUT

Frank O'Leary, manager of the Blanch Field, began to get worried when he saw the storm settle over the hump yesterday morning.

When he failed to get reports of Johnson he began to use the wireless and telephone.

As it approached late afternoon the ships at Concord were ordered out.

The other two crack flyers of the hump, Winslow and Vance, went out.

They could only get a little above Placerville on account of the severe storm, without getting any information.

Pilot Rex Levisee, another of the crack hump flyers, was sent out from Reno.

He could only negotiate as far as Donner Lake and return.

By this time the telephone, the telgraph, the radio and all employees of the Southern Pacific were diligent in trying to locate the missing flyer.

Never were responses given with such heartiness, or arrangements more quickly made than by the Southern Pacific through their chief dispatchers at

both Sparks and Sacramento.

Trains were detailed as a searching party equipped with skiis, webs and airship to Troy.

PHONES BUSY

In the meantime trouble shooters of the Bell Telephone, who were stationed in a cabin out from Tamarack along their lines where they had been doing work, heard the

motor shut off and knew that he must be due for a crash.

They cut in on the telephone and at the same time the train dispatchers hooked in a train wire with the telephone and gave direct communication to Troy,

where Johnson talked with the field manager.

In a few words Johnson told his story and the oldtime trouble shooter linemen borrowed skies and started back to try and locate the ship, and five sacks of mail came through on number 28.

General Superintendent Collins was reached at Cheyenne by FIeld Manager O'Leary and the official's first words were for information as to whether or not his pilot had been injured.

He was told the story, and he then gave orders to remove the instruments from the ship, of which there are nine, and burn it up.

This morning, Manager O'Leary is sending motor macks to Tamarack, where expert mountain men on skiis will try and help locate the lost ship.

As near as can be told the ship lies probably two miles from the railroad southerly, and somewhere near where the highway goes through,

but the prevailing storm last night will obliterate Johnson's trail and it may be some time before the ship is located, if at all, until the snow melts.

LANDMARKS BUSY

To the uninitiated, to those thousands of readers who do not know the high mountains in winter, it may be of interest to say that the view from the air with a heavy covering of snow destroys all the

known landmarks that these wonderful flyers uyse and the view from the ship high above the snow fields resembles somewhat when looking across the divides the teeth of a crosscut saw, the black faces

of the mountain backs, the maws between the gulches, little specks of blac, denoting a few trees and the mounds and contours that look like a child's playground.

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen