Chicago to Omaha to Be Blaze of Light for Air Mail Flyers in New Test Of Defying Darkness

What of the flyers of the night?

Already the men have been chosen for this testing out of Uncle Sam's aerial night driving with the valuable mail.

From Chicago to Omaha the night ground trail has been blazed, and with the coming of the normal weather conditions

in mid-April the great gray moths will streak through the high sky, with their tails of fire and their rumble of approaching storms.

Then while these star shooters and comet chasers are streaking through the moonlit nights, the workers upon earth will be surveying the ground line to

Cheyenne, Wyo., for the last leg of the midnight hurtlers through the vast spaces above.

While the mile upon mile of ground lights are established, then the full complement of night pilots will be added to the personnel in this

great undertaking of Uncle Sam.

[James B.] Jack Knight will be premiere night pilot.

He has been told to take the mail from Chicago to Omaha.

This is the young American who made the record night flight from North Platte to Omaha February 22, 1921.

He then hopped off in the darkness from the Omaha field and started for Chicago on February 23, making the trip without incident,

and landing safely in the Windy City, making the time on what is the regular schedule.

This feature of this unusual accomplishment lies in the fact that Knight had never been over the route between Omaha and Chicago - a feat that still stands to his record,

and to the everliving traditions of the Air Mail Service.

Harold T. Lewis ("Slim") will have the driving of the night air wagons from Omaha to Chicago.

Lewis is the official chauffeur of the official "limousine" of the Air Mail.

The third of the pilots is Eugene C. Johnson, another of the cracks of the Air Mail and one of the boys who had so many thrilling experiences on the Hump run out of Reno, where he made his headquarters

for a number of months.

For several months Johnson has been at Dayton, O., at the U. S. Air field, making tests of the different appliances that are to be used in night flying.

Johnson has been with the mail almost ever since it was inaugurated and is one of the few pilots of the service that has flown the entire Red Line Air road time and time again,

'ferrying' ships = that is, delivering ships to the different terminals of the Air Mail.

Johnson has the distinction in aeronautics of being the first aviator in the game of flying to jump from the wings of one plan to another in mid-air thousands of feet above the ground,

and like most of the pilots of the service is an Air Mail Ace.

The pay that will be allowed the night flyers will be hardly commensurate with the labor performed in this initial tryout of the night game.

These men will receive a base pay of $4,000 a year.

In addition they will draw $5 a day as expense money on the foreign end of the run.

Their travel pay will be 10 cents a mile for distance traveled, in addition to the base and commutation pay.

In the meantime, while the result of the night flight tests is awaited here with keen interest, there is plenty to hold attention hereabouts, due to the winter conditions that now prevail over the Sierras.

It is over and across the California-Nevada mountains that an equipment is used on the Air Mail ships that is unheard of here in the United States or in any other country, an equipment that is absolutely necessary.

It has already been the means of saving pilots who have made forced landings.

If a pilot on this run is forced to land in the great desert basins, the meadows of interminable miles of sage brush,

or if he is lucky enough to head out of this hundred miles of peril, his chances are one in a hundred to escape with his life even in the deep snows of the eternal hills.

The three ships that fly between Reno and San Francisco have one pair each of Siwash webs (snow shoes) safely tucked away in the turtle back

immediately adjoining the pilot's seat in the cockpit.

In this same little compartment there is also stored two days' hard rations, about the same that was the issue to the soldiers of the World War.

Ranging on the side of the cockpit is the new type of life preserver, ready to sling at a moment's notice.

Let it be known that the three ships of the United States Air Mail over the Hump are the only ships anywhere that are so manned.

These pilots have to run the chances of a stalled motor, or a tail-spin, or a hundred and one other difficulties into which a ship may suddently turn.

It may be over the bay at San Francisco. over the great rivers that flow from the Hump into the Pacific.

Then again the ship may head downward straight for bodies of water like Lake Tahoe, Pyramid, DOnner and not less than 21 other smaller lakes that are found in the high rugged

altitudes over which these aces of Uncle Sam's Air Mail travel daily.

Again these young stalwart Americans may have the extreme luck to set down on the crests of the sky line contours, of the ragged snow fields that partly cover a terrain that without

the fifteen to thirty feet of snow, would be death.

He can have a chance to set down his ship, maybe, without crashing into a partly covered rock snag or if the god of luck is with him he may save his ship and himself,

if that same god of luck is with him, by landing on the top of an iceberg, and every thousand feet deep canyon in the Sierras this winter is a true iceberg.

Then when his ship plows into the top smother of snow, he has a chance for his life.

From the time of landing in such a territory the hardship and danger are again multipled.

The pilot would break out the snowshoes from the turtle back, carefully stow away his rations, strap on his webs, and from the great world of white

take a brief survey of the miles upon miles of country over which he would have to travel to reach either railroad, house or village.

His first thought would be of the valuable mail that rests so safely and securely in the mail pit under the wings of his craft.

The intrepids would, of course, create a means to move the mail with him over the blinding reflecting surface of ice and snow.

The glare from the wonderfully brilliant sun would burn and scorch any exposed part of face, hands or body.

Distances are of course the most deceiving in the high places of the mountains.

What seems a few miles will be found to be tens of miles when traveled.

Every step taken, along the ridges, and down the slopes of the terrible mountain slopes, is filled with death.

There are holes and mile-deep canyons that are covered with but a thin layer of snow.

One wrong step and one of these death holes would mean the last of a man.

Now on and on this young American drags his load and slew foots his webs, with but one thought in his mind - to deliver the mail, to keep away from his record

that bugaboo, default.

It is true that these boys of the Hump have thought and planned and tried to visualize just this condition.

Their mail load would of course be conveyed Indian fashion, with lashed poles.

It is good to know that the pilots of the Hump have recognized the importance of making tentative provision for such emergencies and have no fear of what

might obtain if they are forced to make a landing on the top of the world miles from human habitation.

It will be readily understood that they would not have assistance of any kind, with perhaps the one exception of Reno or San Francisco field managers

sending out a ship to spot the set-down - that's all.

It might be possible for the spotting plane to render assistance from the air by dropping grub or in giving direction, as to distances for relief, but that's all - the

grounded pilot would have to depend upon himself to get out of the situation, so fraught with every menance of the great hills.

But these boys would not fail.

The great silver bird, the pride of the flying man, would be doomed, as far as active service for months is concerned.

It would have to be conveyed from its resting place by labor of the Motor Macks, upon skills. The trails leading to the ship would be obliterated

by the every-minute gale of the pinnacles of the moluntains.

In a few hours the ship might be covered with snow dust, and it would have to remain in its resting place until the thaws of Spring come,

and then the disintegration caused by the elements would leave very little of the wonder bird except its warped fuselage, skeleton ribbed, bent and broken winds, and a rusty motor.

Still, it would be found and brought out - at least the parts worth using again.

The number of the ship would then be brought out from the sketon plane, and a new ship would be builded around and about that number - because a pilot wants his ship number.

Pilots are very partial to the number of ships in which they have made record flights.

They are just a bit superstitious about the number of their craft.

It has been a lucky number for them, and it creates faith and is in fact part of them just as surely as psychology can make it.

Today under every flag on the face of the globe men are engaged in flying.

In peaceful, commercial pursuits, in grim war, and for pleasure.

The many governments are spending their millions for new and wonderful birds of the air.

The toll of life among airmen today is almost zero, where they are engaged in straight flying.

All over the world machines have their special equipment, have their hazards.

Safety devices are legion, in the parachutes; in the new appliances that reduce the element of fire to a minimum; in landing gear that save; smashups; instruments

that tell the pilot many of the dangers that are easily overcome: the radiophone whereby the driver of the air can be in constant communication with the forces below.

On the regular passenger and commercial air roads there are many perils.

Many are the water and mountains tretches that are crossed daily in safety.

Tales of the daring of these airman matters of story, affording a paragraph in the daily papers.

It is all so commonplace now that it is a very rare circumstance that an event of daring contains a thrill to the waiting world.

With all this before us there is nothing even comparable to the everyday dangers experienced by the American pilots that delivered the Transcontinental Air Mail Red Line road

from Reno to San Francisco.

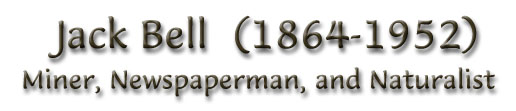

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell.)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen