Government Fliers Who Carry Valuable Cargoes

Over the "Hump" Live Lives Filled with

Thrills and Danger; Men are in

a Class by Themselves

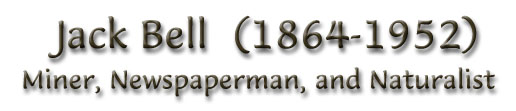

By JACK BELL

(Copyright by Jack Bell)

The hooded,

goggled wonder-men of United States Air mail who carry the valuable pouches from Reno to San Francisco

over the "hump" are in a class by themselves.

They are all rated as the premiers in danger flight.

They are the peers in this branch of government service, and hold all speed and altitude records for the air mail.

They have been and are the picked men of this service for physical and

mental strength.

A group of young men they are who have the initiative and endurance

to overcome the multiple hazards of the terrible, terrifying 100 miles of two-mile-high

peaks, of mile-deep canyons, great fields of giant boulders, forest-covered screens of the

hundreds upon hundreds of death holes that lurk below the seeming lawns

of the vast expanses of the almost unexplored mountains on the western

shed of the Sierra mountains in California.

From the 16,000-foot altitude the long slits

leading into Sacramento valley resemble miniature playgrounds, being the miles

upon miles of gulches and gorges, from which the little mountain streams flow ocean-ward

and make up the navigable rivers that lead on and on into the Pacific.

HAZARDOUS ROUTE.

This 100 miles of Red line (the government's line of flight) is recognized the world over

as the greatest hazard in aeronautics for any kind of aircraft. This danger applies to balloons, dirigibles

and aeroplanes for the reason that there is absolutely not one single landing place

for the entire 100 miles.

As a matter of fact, it would be sure and certain death for a

ship to even try to land, on account of the rugged terrain. There is not a clearing of any sort

or kind of place to land a plane.

The "hump," so named, is the point of highest crossing of the

Sierra Nevada mountains on the air lane.

Coming eastward from the "hump" are the rocky. broken defiles sloping down into the Truckee river basin, where the city of Reno is situated.

There are no landings of any kind whatsoever on this 40 miles of air line and the dangers to the pilots are the same on the Nevada side of the "hump".

Over the little lumber town of Verdi, about twelve miles westward from Reno, is what is officially known as the roughest place of record in air flying.

It is here that all the winds of the vast expanses of mountains and desert converge and meet.

The air currents may take the pilot and his ship miles out of compass course: they may take him and his ship up into an altitude of 17,000 feet

from the landing level of 12,000 feet that is the usual altitude taken for a landing at the Reno field.

Again, the "bumps" may strain the holding belts of the pilot to almost the breaking point as the staunch ship strikes with a force that almost dislocates

one's neck with the terrific impact.

The wonder of wonders is how a ship stands the terrific forces and strains of the elements.

One would think that the singing wires and struts would part and splinter so great are the blows that hit the machine.

As the pilot fights for his very life, he watches the wings of the wonderful craft, expecting the wings to fold and the ship to drop wingless into

that vast space above the earth.

CLOUDS INCREASE DANGER.

Of course the element of danger magnifies when the sky clouds and the "hump" is covered with fog.

It's doubly dangerous for the reason that the ship may drop from the force of an upper current and be forced down upon one of the thousand rocky

peaks - where the pilot has no control.

It is during this weather that many times, with the thermometer registering down towards zero, the pilot steps from his ship, dressed in

his heavy winter suit and frost-covered and tired from his awful battle, covered with perspiration.

Many times the altimeter will show 12,000 feet, and in the twinkling of an eye the pointer will show on the dial that the plane has dropped to 8000 feet

or has lifted to 16,000 feet, or suddenly drifted miles from the Red line course.

In the desert flying east almost the same danger obtains, with the added menace of the terrifying sand and wind sprouts.

One of these twisters will take a ship whirling into space as quickly as if the 4200-pound plane was a feather.

It is again up to the initiative and nerve of the pilot to save his life, the mail and the ship.

However, he has the advantage of being able to make a rather safe landing on the many great flat spaces of the desert and almost always without

injury to his ship.

The dry official record of the feats of skill and dogged determination to fly the mail 100 per cent through all the death-dealing elements

encountered on these runs reads between the lines like wonderful, impossible fiction.

FLIERS FEAR LIMELIGHT.

These hardy young Americans are the most close-mouthed lot that exist.

To get the story of one of these danger experiences one has to use all the craft and art of the seasoned newspaper man.

They are so afraid that they will appear in the light of trying to be a hero. Of course, there are exceptions among pilots just like everything else.

But it's rare for the real chap to recount with boasting or conceit any of these experiences.

All of these boys have 'flying hours' that mount up to 3000, and figured carefully, this means that they have flown a distance of 300,000 rniles

through the air.

There is one ship on the Reno field that has a record of almost 50,000 air miles without overhaul:

This ship was built by the "Motor Macks," the mechanics, at Reno field.

Not that these boys on the "hump" run down do not have their close calls to death - they do and very often.

Just recently one was lost in the dense clouds that come down to earth, and up in the sky for miles - he could not get out. He flew and flew,

with all the knowledge of his long career in the air.

Then his motor began to sputter, and slowly, slowly, slowly it idled down to a full stop.

A half-dark Spot was picked out and the boy headed his ship for a chance to "set her down."

It was the top of a hundred-foot spruce tree - a wing was torn away, and the ship, nose down, crashed into the smaller growth of pine and buried

the nose of the ship and the motor into the ground.

Strange and wonderful as it may seem - impossible as it would appear - the pilot was thrown from the cockpit to his feet.

The crash was heard two miles away and timbermen hurried through the dense fog and found the pilot in a dazed and bleeding condition

walking about the wreck of his pride ship and saying, "I couldn't keep her up with only one wing."

He lapsed into unconscienceness.

He was hurried to a hospital some miles away - where he remained unconscious for five days, skinned and cut and bruised over his entire body.

This boy now fies the "hump" every other day.

LOST FOUR HOURS.

A few days ago another chap of the same caliber was lost in the clouds for 4 hours and 21 minutes.

He sailed and sailed, he flew high and he flew as low as 12,000 feet, but no opening.

Once when the dense darkness overtook him, he thought he espied a field - from the change in temperature he knew that he was well out of the dangerous

zone of rocks and canyons and mountain peaks.

He took a chance to circle down; then, wonder of wonders, he made out a hangar at Mather field a mile out of Sacramento, and landed without mishap

in the dense gloom of the abandoned army air field.

Is it just luck, or is there a higher power that looks after these stalwart, clean-living fine, upstanding young men who are doing this work

for Uncle Sam?

Another of this trio, and recently, had another experience that is a record in that he, by his knowledge and downright nerve,

saved himself from death.

He was flying at 12,000 feet.

Without any warning the motor went dead, the plane went into the deadly tailspin in a flash.

With the cool desperation of knowledge of impending disaster, this boy used all his known arts - and they are legion - and at 6000 feet

the motor sputtered, took on, and he leveled his ship.

This also was over Sacramento.

SPEED RECORDS SMASHED.

The names of these intrepid flying men will some day be graven in letters of gold, with their records of early achievement in the archives of the

United States postoffice department - when they are laid away in the years to come.

They may well be proud of their brilliant records, the records they are daily making that will appear as obsolete in just a few years.

But their hardships, their pioneering over the awful hundred miles of this mountainous divide will live forever.

Speed records are smashed and knocked to smithereens every few days.

Two hundred and twenty miles in one hour and thirty minutes is done every day.

Forty miles of this, measured from the "hump" point triangulates this distance from Reno field.

Daily the mail ship comes down from there from the usual altitude of 12,000 feet, and covers that course in less than ten minutes.

Figure that and then talk of speed records - speed records made under prearranged precaution, tuned, tried out ships, practice flights and all! What?

The boys think they are losing time if they consume over 22 minutes coming this last forty miles.

San Francisco is measured and reckoned as 205 miles triangulated distance from the Reno field.

The ships generally fly 225 to 250 miles distance.

The record so far, officially, is one hour and 19 minutes, timed from the time the wheels leave the earth until they touch the ground at terminal.

The field managers and the assistant superintendent file and report the time of arrival and departure of the ships with every care.

The most noticeable feature of the air mail service, and this is speaking for every man connected with this leg of the Red line,

is the inordinate pride, loyalty and the co-operative functions every department.

EYES GROW LARGER.

Recently one of the pilots was asked to have an examination of his eyes made by a local occulist, after flying the altitudes up to 16,000 feet

for almost two years on the San Francisco run.

For months it has been noticed by friends of the boys that fly the "hump" that their eyes were growing larger.

The eye balls and iris were abnormally large.

It was proven that they have become men of such long range of vision that objects on the earth, and in the vast expanses, are clear and plain to them.

Objects in the hundreds of miles' expanse of view from the ship can be plainly seen and accurately described long before the object can be seen

by the ordinary person.

On the field these fliers of the "hump" can plainly see a ship in the vast expanse of the sky when it is a difficult matter for the ordinary person to make

it out with glasses.

The eminent occulist here says that these are the first cases of extended clear vision of great distances that have been noted by his profession.

He further states that nature is providing this wonderful far-seeing that is known to exist in the deer, antelope, burro and other animals of the great

high, open places.

Then again, as a matter of fun, the close friends and acquaintances say that their near vision is disarranged, for picking out details of close

proximity - citing as proof the girls and women folks they accompany to dinners and theaters.

Believe me, one can get an awful rise out of those flying men when they mention their lack of finesse in taste for feminine beauty.

There are but few of the air men are married.

NEVER AGAIN.

A few days ago one of the pilots returned to Reno from the San Francisco field in the mail pit of the ship.

When the plane was landed he hurried from the mail pit, and looking at the ship said:

No more of that kind of flying for me - never again."

"Why; what's the matter," he was asked.

"Say, I'm not jollying a bit." and he was in deadly earnest.

"I was scared stiff all the way up from San Francisco.

The terrain didn't look right, under me. Everything was so confounded different.

It certainly is no pleasure now when I drive a plane.

Well, of course, that's different.

I know every shake the ship makes, but up in the mail pit - it's strange ground and the crate don't seem to fly right

- and all I thought of was that something might happen and she would take a dive or a hundred other little things that make up the stunts

that a ship is liable to do.

"Never again! Not for all the money in the country would I make another trip in a mail pit - and one of the regulars, old-timer on the run,

was driving, too. No sir: not me!"

This is a seasoned pilot, too.

He has thousands of air miles to his credit on the Red line road, and has had many a narrow escape from the supreme crash.

Brilliant Records are Made Daily by Aviators in

Airmail Service Who Make the Hazardous

Run from Reno to San Francisco

and Return Over Sierras

"158" HOLDS RECORD.

Vance and Harry V. Hukings are the aces of the United States air mail flying Reno-San Francisco.

Ship No 158 was the plane in which Vance made the wonderful record from Elko to Reno, 1 hour and 20 minutes.

No. 158 is now flown by Winslow and holds the record for mileage in the air for the entire Red line road.

Every few days Winslow brings this ship into Reno from San Francisco in 1 hour and 22 minutes, and coming daily from the coast in an hour and a half

is just ordinary for the flight that is marked 190 miles, but is flown over 200 miles daily.

The record from San Francisco to Reno is held by Boggs. testing pilot at the San Francisco field.

He made the phenomenal time across the "hump," but in a light ship, of 1 hour and 19 minutes, a record stands.

The other records and the time made by these pilots is under regular mail carrying conditions.

The weight of mail carried varies from 300 to 500 pounds daily on the fast delivery of Uncle Sam's air mail service.

William F. Blanchfield formerly flew the "hump."

He is now on the run between Reno and Elko.

This pilot has an official record of one German plane over Bruges, and three unofficial.

For three months he was in a pursuit group during the World War.

He is second to none as a pilot and is rated by officials of the air mail as the most natural flyer in the service.

He has brought the mail [xx] managers have pleaded with him not to take a chance.

Through the winter storms, the gales of the desert's blinding, cutting storms, when the paint and varnish of the plane

would be scratched and scored by the violence of the winds. the records made by Blanchfield in his

wonderful flying show that danger means nothing to this intrepid man of the ship.

He has more flying hours than any man in the service and therefore is a past master of a ship under all conditions.

LEVISEE SET MARK.

Rexford B. Levisee, formerly of the "hump" crew, now flying Elko-Salt Lake, made a record over the "hump" that will long live

in the memories of the hundreds of friends and acquaintances of this master of a ship.

Then there is Ray Little, of the early flights; Morgan, and Boggs, all men of valuable worth to Uncle Sam in his early inauguration

of the air mail. Their deeds are still fresh in the minds of those that knew of their records of inestimable worth to the government.

There are other pilots that share in the function of the successful administration of the air mail.

The list is too long to qualify.

They are all good men or they would not be in the service.

There is not a single pilot mentioned that courts publicity.

Matter of fact, they are all of the close-mouthed type.

The only word one can drag from them after some awful hardship and heroic effort is, "I was sure scared today."

That's about all, with the added afterthought, "Well, it was pretty rough today."

"The clouds were [xx] ground."

There you are. Even when one of them is cornered and queried he will in all likelihood make some excuse and run away.

When talking among themselves it's about the same thing, too - no thought of self-aggrandizement, and absolutely

no element of conceit, and they actually shun anything that may appear to court publicity.

On any other subject they will talk interestingly.

Some of these flyers have official German planes to their credit during the World War. All of these pilots have fine service records,

both overseas and at home during the big show.

Burr H. Winslow has had his fill of narrow escapes.

Even in training he had many hair-breadth escapes from the big "crash."

He is one of the early pilots of the air mail.

His first big crash came just after he had been assigned to the air mail, when it was a tentative testing matter of experiment by the postoffice department.

FACES TERRIFIC STORMS.

After riding the eastern legs of the Red line, Winslow was assigned to the Reno-San Francisco run.

He came when the weather was at its worst last winter and flew almost the entire season without serious mishap.

There were many, many days when he would try to face the storms of the "hump" and make the "hump" - and at times remain in the air for hours

endeavoring to pierce the dense snowstorms, clouds and hurricanewinds.

On October 22, last, Winslow left the field at San Francisco.

There was nothing but clouds - fog, the deadly bank of mist that all airmen dread.

Winslow nosed the ship straight up the fog bank and clouds until his altimeter read over 17,000 feet, when he came into the sunshine.

He headed his plane for Reno. He departed at 2:17 p. m.

He actually flew over and around Reno at this altitude.

He could be plainly heard in the high distance. No visibility.

He turned tail and started for San Francisco, that is, in the general direction.

Matter of fact, he said he was lost.

He dived and dived over that vast sea of clouds.

He circled and headed in and out of the dense mist.

All to no purpose. Absolutely no visibility and no "hole" to take a chance to try for the terrain.

He headed again towards dark in the general direction of west.

Just at dark he noticed a change in the atmosphere and took the chance that he was out of the 300-mile area of no place to land.

He spiraled down to 2,000 feet. He saw a hole, that looked like a field.

He slowly circled as low as was safe and discerned a corner of a hanger at the army post at Mather field, three miles from Sacramento.

He landed in dense darkness this abandoned field. Hurriedly getting in communication with the postoffice at Sacramento, he delivered the mail.

He had been in the air four hours and 21 minutes.

All this time every telephone, telegraph and radio office was searching for the lost ship.

When interviewed by Sacramento newspaper men all that could be dragged out of him was:

"It was mighty lonesome up there, and my gas and oil were getting darn low."

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell.)

Next week Mr. Bell will take us with other intrepid airmen over the perils of the "hump."

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen