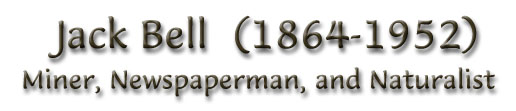

An Authentic Recital of the Dramatic Combat, Written by One of the Men WHo Took an Active Part in It

(BY JACK BELL)

"Now, there is all kinds of danger in the job and I don't want you to take it if you don't want to.

Besides, you may become an object of suspicion among the men," said the manager to me as we sat about the office of the great $10,000,000 Independence mine at Victor.

Ore thieves had been descending at night into the workings and stealing thousands of dollars worth of rich ore.

"What does he care - he's not afraid of the thieves that are coming in the mine stealing the ore - and the men on the mine will understand what he is there for,"

interrupted Sam Lobb, the superintendent.

"All right, Jack, go down tonight and hide yourself away some place where you can command a good view of NO. 2 shaft."

"Shall I take a chance with the thieves?" I asked.

"No, don't do that. If they come in, get on top as soon as you can and notify us. We will be waiting up here in the office," answered the superintendent.

This was on Jan. 14, 1902.

Without the knowledge of any of the men outside of the staff and the watchman, I quietly went down to the 400-foot level on the "dinky" a little after midnight.

Alexander MacDonald, one of the shift bosses, went with me.

We went through some of the workings on Four just as we have always done, so as not to excite the suspicions of the miners.

We went back to the junction of the Emerson and Independence veins, called the "narrows" by the men, and looked about for signs that would give us some idea of points of vantage.

Directly in front of No. 2 shaft is a crosscut that connects with the Strong property, which commands an open view of the unused shaft.

I cached myself about twenty feet from the main drift at the junction of the Bob Tail vein at 2 o'clock in the morning, to be out of sight of the men when they came off shift at 3 o'clock.

I made myself as comfortable as was possible, put out my candle, pulled on my gloves, leaned up against a pile of muck with my six-shooter in my hand, and, as the miners came out after spitting their holes,

began my lonely watch.

Terrible Darkness.

There is no such darkness, and there is no such quietude as there is in the interior of a big mine.

There was not a sound, and the oppressive silence was only broken by the pendulum-like dropping of the water, which increased in its loudness as the hours wore by, and the occasional dropping of loose dirt into some of the chutes.

The latter sounded like field artillery, to my strained nerves and pent up nervousness.

I argued with myself, and planned all sorts of impracticable maneuvers to consummate in case the three thieves made their appearance.

I knew that they were desperate men and I had come into the mine prepared for any emergency.

If they ran into me, it would be a case of quick business with the pistol.

Indeed I wasn't in a very comfortable frame of mind, and I hailed the tramp of the night scavenger with a joyful feeling, for I well kinew that he3 would come to 400 a bit after 4 o'clock.

"They will not come in tonight," I said to myself with a heap of relief.

They could not possibly climb down that 600 feet, load up and climb up again before daylight, because they would be seen leaving the old shaft house, which is near the Portland offices.

However, I remained on guard until 6 o'clock.

I arose and almost fell down.

I was stiff with the cold, and my legs were "asleep."

I came out to the main shaft and gave the signal on the "dinky" bell agreed upon by Jay Miller, the hoisting engineer.

He lowered the little cage, which hung just above the level, and quickly hauled me up on top, and, you bet, I took a big long breath of relief; as I said: "Not a move

tonight."

We were both pleased.

I reported the next night, January 15.

At 1 o'clock Miller lowered me and I got off at three hundred and walked down through the "Bull Pen" to the "Narrows" on the 400-foot level.

I wore an overcoat and was well fixed for lunch.

At this point in the mine, the Jewelry stope is square-setted from 500 up to the "Narrows."

It is five sets across.

I went down one set and three sets over from the junction and fixed myself behind a timber where I could see all approaches coming from No. 2 shaft

into the Emerson and the Independence.

The men came out, the thunder of the blasts had gone, and I had just fixed myself in a position that I could keep indefinitely without moving, when I heard the crunching of the dirt on the tracks

coming from the direction of No. 2.

The Crisis Approaching.

My heart jumped into my throat, my ears were strained and every sense was on the alert.

On they came.

I could hear the mumble of the low spoken orders of one of the gang, as they would stop and listen and then advance slowly,

feeling their way by the flashes of some kind of an electric lamp.

When they reached the "Narrows" they stopped for some little time, it seemed hours to me, and I half imagined that they were arranging to make a concerted

movement against me in my hiding place, but they were only lighting candles and making ready to go down into the Emerson stope where there were plenty of rich "glommings."

It seemed an interminable time before their voices died away.

With a carefulness that I did not know that I possessed, I arose and made my way to a ladder that went up on the level fifty feet from the "Narrows."

In the darkness, with the light steps of a cat, keeping one foot on the outside rail of the track, by slow degrees, I made my way to the maind rift 400 feet away

and there lighted my candle for the first time, then with a regular step and without any unusual haste I made my way to the main shaft, pressed the electric button

four and two and the "dinky" came to me in an instant.

The signal meant that the desperate thieves were in the mine and I was whirled up on top in a jiffy.

The Thieves At Work.

"Well, Jay, they are down there," I said as the engineer came toward me.

"Where did they go?" was the first query.

"Dunno. The last I saw of them they were going into the Emerson, past the "Narrows."

Just then Fred Strickland, the night watchman, came running out of the change room and joined Miller and me.

We well knew that there was desperate work ahead of us with the possible chance of getting a bullet or two in our skins.

Mr. Shipman was called on his private phone from his house and he was at the collar of the shaft before we got rightly turned around, dressing as he came.

The watchman and the engineer hastily summoned Alexander MacDonald, shift boss, and Lee Glockner, the foreman of the ore house.

These arrangements were perfected in the almost incredible time of eight minutes.

As I looked at my watch when I reached the station on 400 to go on top it was exactly 3:40, and when we were getting on the cage to go down it was 3:48.

"We will get them this time," said the general manager, after he had satisfied himself that we were all properly armed.

Mr. Shipman, Alexander MacDonald, Lee Glockner, Engineer Miller and Watchman Strickland rushed from the cage at the 400 and we all went quietly to the junction of

the Independence where it connects with the main drift, about 500 feet in.

We all stopped at this point.

"MacDonald, you and Glockner go back into the narrows with Jack and place yourselves in the cross-cut directly in front of No. 2 shaft," said Mr. Shipman.

"I will take Miller and Strickland with me and we will go around the Emerson stope and join you there.

If these men are in this part of the mine there is no way in which they can get away from us.

Be careful, boys, and take no chances, because these fellows will shoot and may hit some of you."

We went back to the "Narrows" and sat there for a minute with our lighted candles, when I suggested that we go on back into the cross-cut where Mr. Shipman had ordered us to go.

Mr. Glockner thought that we had a point of vantage and suggested that we remain where we were.

A second time the orders of Mr. Shipman were presented with the same answer returned, on the theory that the men were down in the flat under the track, and that this was a good position in which to have the advantage

of the thieves.

In a few minutes our party was increased by the arrival of Assistant Manager Grant and Shift Boss Gill, and we all stood about the crossing, leaning against the walls, chutes

and big posts in silence.

Flushing the Game.

Manager Shipman and the two stalwart watchmen went on back into the Emerson.

Down in the stope about forty feet from the level they saw three men sorting the ore that was piled in two big heaps.

There were snuffs placed all about where they were working and they were picking out the rich sylvanite and putting it in the skirts of the hunting coats that they wore.

"Hey, what are you doing there?" the manager cried to the thieves.

The robbers put out their lights and made no reply.

"Come up and surrender and no harm will be done you."

Still there was no answer.

"I'll count ten and if you do not light your candles we'll shoot."

The manager then counted ten good and loud, and the three men fired a volley, but not in the direction of the men that were under them.

Again the mine manager counted, and again they fired a round.

After this second volley, which spattered about the men down in the stope, a voice cried out in all the fierceness of a hunted beast, with savage oaths:

"You will never take us out of here any way but feet first - and you can bet that some of you will go on top in the same way - we will kill somebody."

The loose rock began to roll down through the stope to the 500-foot level as the desperate thieves started toward No. 2 shaft, guided by the white gleams of the electric torch.

The party at the junction of the "Narrows" never heard a sound of the shooting that had been done by Mr. Shipman's party.

In a voice that sounded like the desperate commands of an officer on the field of battle came the startling roar of a man crying with a fierceness that would chill the blood in most men's veins:

"Now, we have got you, you _ _ _!

You can't get away from us _ _ you!"

Never in this world or the next do I expect to hear such cries or curses, and that voice I will hear to my dying day.

Big rocks were started from their places and rolled down to the next level with a thunderous roar.

We could not see the men who were making the noise, but a fitful light,

which proved to be an electric candle, threw long gleams of white on us, as we gathered about the crossing,

with flickering candles, perfect targets for the desperadoes, who were coming straight at us.

There is an area of about ten feet square at the "Narrows" and the thieves would have to pass within a few feet of us to get by; in fact, we would be able to reach out and touch them almost.

A "Ticklish" Period.

Coming through the drift in which there are many posts at intervals of about thirty feet, a pistol shot rang out from one of the robbers.

It was followed by two shots in quick succession by Glockner, which drew their fire.

He was directly in front of the rest of our party.

Bang, bang, bang, went the big six-shooters, as the crossing filled with the powder smoke.

We all snuffed our candles at the first shot and made for places of safety.

We could not fire as Glockner was directly before us, and when the candles were put out it was unsafe to try a shot.

I fell down on my stomach close against the wall of the Independence drift, back of Glockner, and the rest of the party got into places of safety

behind the cutes and the posts that held up the square sets.

I heard Glockner stumble, as I crawled back to the drift and the bullets from the pistols fired by the robbers were spatting all about us, with a very discouraging thud, thud, thud.

There were about a dozen shots fired and it was all over in less time than it could be told.

The battle was not in progress over three minutes, although it seemed to last an interminable time.

We thought we heard the men make back in the direction of No. 2 shaft and we got our candles lighted and looked about us to see if any of us were missing.

Lee Glockner was not there.

Just then there came a faint cry from down in the square sets:

"Goerge, ho, George," came the labored almost unintelligible accents of the voice from down in the depths of the square sets of the Jewelry stope.

Mr. Shipmen joined us at this time and told us that his party had had a running fight with three men who were down in the Emerson stope under the level.

A great many shots had been exchanged, but that no one was hurt.

He inquired the direction that the thieves took and ordered Gill and me to look after Glockner.

MacDonald and Strickland were sent to 200 to watch the shaft at No. 2.

Miller went to the collar of No. 2 on the surface.

Grant went to the surface to notify all the properties connecting, and other men went to 500.

As the whereabouts of the thieves was but a matter of guess and no one suspected for a minute that they could make their escape from No. 2 shaft, men

were posted at all of the abandoned shafts in the vicinity.

At this time Sam Lobb, the superintendent, arrived at the mine.

He had been called away to sit up with one of the miners who was sick.

He went into the mine, taking men with him, to look for the thieves.

Every arrangement that the manager made was carried out to the letter without any hesitancy or delay.

Glockner's Peril.

George Gill clambered down the ladder after Glockner from the Emerson side of the sets, and I went down on the Independence side.

Gill found him hanging on his side over a two-inch piece of iron pipe that had been thrown down the stope out of the way.

The ore boss had caught on the slender support.

Had the pipe not broken his fall he would have gone down a sheer drop of 100 feet and been

crushed into a shapeless man of humanity.

He had by the merest chance landed on the pipe which was across the sets and eighteen inches from the square timbers against the wall.

He had fallen down - head foremost and his escape from death is one of the things never to be understood.

Gill helped him from his perilous position and I joined them and helped to carry him up the eighteen feet,

that is, up two sets of timbers to the level.

"They have got me," he said between gasps.

Both arms were useless and he breathed with the greatest difficulty, repeating over and over again that the robbers had shot him in the side.

We took him to the station, one on either side of him, and quickly had him on top.

The blood was streaming from out either sleeve of the hunting coat he wore.

The ball in the left arm had entered at the elbow from the rear and shattered the joint, while a nasty flesh wound was in his right forearm, which had entered from the back.

"I saw the flash of the electric light and the flash of the pistol, and fired at nearly the same time that the robber did," said he.

"The front man shot me in the right arm and the man behind the first thief shot me in the left elbow.

I fell, and in trying to get up, I stumbled and went down the stop in the square sets."

His ribs were caved in and we thought that he was about "all in" when we examined him that morning of the 16th of January.

Physicians were hastily summoned and the wounded man was taken to the residence of Mr. Shipman, where he lay in a precarious condition for almost two months.

But he was able to appear against these men on the 28th of February, when they were brought up for trial.

The Chase Continued.

Juas as it was breaking day we heard the reports of two shots coming from the direction of the No. 2 shaft.

Miller soon came in and reported that he had fired upon three men that had come out of the shaft house and who ran in the direction of Goldfield.

Still, we thought that they might yet be in the mine and our vigilance was not relaxed.

Extra men were summoned and all placed of outlet were guarded by determined armed men who had "been through the mill" before,

and would like nothing better than to have a chance with the thieves.

The miners had taken the shooting as a personal affair, for the reason that the missing of large amounts of rich ore reflected upon their honesty,

and if there is one thing a miner despises it is to be suspected of being a "glommer," that is, an ore thief.

And when the sun came up in the early morning, armed men were seen walking their beats on the surface at the different openings.

Gill, Miller and myself went down in the mine and climbed down into the Emerson stope, where the thieves had first been seen.

We found where they had been uncovering two caches of rich ore, in one of them I found the torn letter that gave a clew.

There was about half a ton of picked sylvanite and rusty gold rock, grab samples of which averaged $8 per pound.

The ore thieves had made the climb up the ladders of the old shaft for 600 feet in the phenomenal time of eighteen minutes, as near as we could figure it.

Four sets down from the collar of the shaft, a distance of twenty-0eight feet, there were no ladders and the bandits had buckled heavy strapes over the timbers and

swung up sailor fashion, a most dangerous and thrilling means of entrance and escape.

Sam Lobb let himself down the No. 2 shaft with a rope, and, between the one and two hundred levels, found the thieves' ore sacks which they had dropped and the bulls eye of a lantern

which had been melted from its frame.

In the meantime, Gill, Miller and I came up through the shaft, and found the torn bits of another letter that, when put together, proved to be a missive

signed John B. Freidenstein.

Several empty shells were also found by myself, Billy Campbell and John MacKenzie, shift boss.

All of these things were placed in envelopes and carefully sealed and marked.

Gill and I made another trip to the place where the ore was cached, and found in the place where the men had been uncovering the rich pile of

high grade ore, several more scraps of letters that when put together proved to be a message

received by Freidenstein from Red Rock, Colo.

These two torn letters were the only clues that we had found that were likely to lead to the apprehension of the men who had tried to commit murder.

All of this work was done by the time the sun had begun to light up the hills.

The Pinkerton's Summoned.

Mr. Shipman called up the hotel at Cripple Creek and being informed that John C. Fraser, superintendent of the Pinkerton National Detective agency, was there, sent

an urgent message that he come over to the mine with all possible dispatch.

This detective, of international reputation, ran half-dressed to the high line on Myers avenue and was lucky enough to catch a car.

He knew Bart Smith, the motorman, and told him that it was a matter of life and death and that he must reach the Stratton Independence mine with all the

speed that he could command.

Smith yanked over the lever and without a stop swung around the dangerous curves, up and down hill, and made the run to the mine in twelve minutes - a run that will never be equaled.

The veteran criminologist was in the office of the mine at daylight.

I gave him all the information that I possessed, as did also Mr. Shipman.

Fraser interviewed a few more men about the mine, took the scraps of letters that I had put together, the empty shells and all the rest of the evidence

that had been picked up, and sped away for the high line car and was back to "the Creek" before 8 o'clock.

The famous criminal hunter had "a line" on the men, had communicated with Sheriff Robertson and, in two hours from the time that he had left the mine, had

caused the arrest of Kirch Kuykendall, Hartley J. Lake and John B. Freidenstein.

Lake and Kuykendall were found in a house they were batching in on May street in Cripple Creek and Freidenstein was picked up in Anaconda.

The two men arrested on May street were in their beds with their clothes on and two 38-calibre Colt pistols were found hidden in the room.

Fraser also found the electric torch in a flour bin, and all the other evidences needed to prove them men who had followed the business of stealing ore.

Link by link the chain was forged by the detective and on February 28 the case went to trial.

Among other things that were found in the house occupied by Kuykendall and Lake were several chunks of rich rock that had been roasted in the stove, pieces of ore that looked like big nuggets of gold,

so rich was the quality of the stuff.

When the detective investigated the habits of the men Kuykendall and Lake, he found that they were expert pistol shots.

They could, at twenty-five feet, hit the smallest target in a shooting gallery five times out of six.

Both men had shady reputations and neither had been known to have worked for months, although they had plenty of money at all times, and were considered very dangerous men.

Conductor Graves, of the High line, had carried these three men at different times and always in the early hours of the morning - his testimony was of a character

that left no room for doubt as to the men who had been in the mine on the morning of the 16th and had shot the employee of the Stratton Independence.

These three men got off the car at a point near the mine at 2 o'clock on the fateful morning and they were positively identified by the conductor at the trial.

The Thieves in Jail.

Two days after the shooting, Mr. Shipman and Mr. Grant visited the county jail.

As they were passing by the cell that was occupied by Hartley J. Lake, he cried out to another prisoner:

"S-a-y, will one of you fellows give me a match?"

Both visitors wheeled about as thought they had received an electric shock.

The voice was the identical one that had hurled curses upon them in the mine on the morning that the battle took place in the bowels of the big mine.

There was not a particle of doubt but this was the man who had man the terrible outcries while banging away at the officers of the company.

Mr. Shipman filed a direct information against Kuykendall, Lake and Friedenstein, charging them with conspiring to kill H. A> Shipman and Lee GLockner.

The state's attorney, Trowbridge and Cole, were assisted by J. Maurice Finn and Silas D. Crump, the two ablest criminal lawyers in the state,

while the court appointed Judge Salisbury, Eugene Engley, attorney general of COlorado under Governor Waite, and a boy by the name of Hodgson, just admitted to practice,

to represent the three prisoners.

The case was called up for trial before Judge Seeds in the district court in Cripple Creek on Feb. 28.

The court room was packed to overflowing, and there was a breathless silence in the hall of justice as the prisoners were arraigned.

The unbroken testimony of the employees was given, all of which was substantially as has been related in the foregoing, the vivid

description given us by the men who were engaged in the battle kept the crowds in breathless suspense as to what sensational feature would be produced next.

Kuykendall assumed an air of bravado of the cheap variety and posed for the edification of the big crowd that was behind him.

Depended on an Alibi.

The defense then began to call witnesses to prove an alibi.

James James was the first witness called, and said he had seen Kuykendall and Lake at the residence of S. E. Kuykendall, the father of the prisoner,

on the night of Jan. 15.

The father and the sister gave like testimony, as did Mrs. Rose Redmond, C. L. Killiam and Claude Maxwell.

As the three latter left the stand they were arrested on a bench warrant charging them with perjury.

They were all taken to jail quietly and the public knew nothing of the circumstances until the following morning, when it was made known.

It was the ranked piece of fake testimony that was ever offered in court, and was by all considered a shame and an outrage on justice.

On the night of March 3 the arguments began.

Mr. Finn, for the state, made an argument that will live forever in the minds of all who heard it.

It abounded in word-painting that gave one the shivers, and as a dramatic effort it was superb.

He tore the prepared alibi to shreds, and when the vital question arose as to the ownership of the electric lantern, he held the audience spellbound.

"They say," said he, "that this lamp belongs to Freidenstein, who has been a witness for the state, and that it was purchased by him in Denver, on Larmier street.

It is the property of this man Kuykendall, who purchased it in Boston."

Kuykendall interrupted with: "You are a liar," and made a motion toward the attorney.

He was handcuffed and given in charge of the deputy sheriff.

Attorney Engley kept interrupting the lawyers, who were scathing in their criticism of the manner in which he had tried to put up the alibi.

He was cautioned by the court, but paid no attention to the warnings.

Engley made a strong plea for the prisoners and also indulged in personalities, as did all the attorneys, with the exception of Judge Salisbury.

At the conclusion of the arguments, Judge Seeds, in a mild tone of voice, said:

"All of the counsel engaged in this case will remain in the court room after the conclusion of the case."

When the room had been emptied of the crowd, the judge told Messrs. Engley, Finn, Hodgson and Crump to appear in the court the following mmorning and explain their conduct.

The attorneys were fined in the following order for their actions during the progress of the trial: Engly, $75; Finn. $25; Crump, $25, Hodgson, $10.

Before the day passed Crump was notified that his fine was remitted and the charge of contempt expunged from the records, but the rest of the attorneys

paid over their fines to the clerk.

On the evening of March 7 Engley and Hodgson were arrested on the charge of subornation of perjury, and were taken to the county jail.

Engley was released on bond, but Hodgson could not get the surety.

Their Attorney in Trouble.

Killam, Maxwell and Rose Redmond were taken before Judge Seeds on the morning of the 8th, and each made the sensational statement that Engley had

put the form of the alibi before them, and that they were to have received sums of money for so doing.

Mrs. Redford's case was then postponed, after the self-confessed perjurers made their statements and asked for the clemency of the court.

The cases of the woman and George Wimberly and Andy Sellars, who had upon this date been arrested for being implicated in the same alibi deal, went over to the 10th of the month.

The jury went out on the evening of the 5th, and on the morning of the 6th returned a verdict of guilty as charged in the complaint.

ON the finding of this verdict of guilt the fast failing strength of the elder Kuykendall gave out, his heart was broken, and he passed quietly away,

when the news of the conviction of his only son reached him.

Sensation at a Funeral.

On Sunday, March 8, the funeral of the father of the young desperado took place, Kerch Kuykendall, the "Philipino Kid" was there in attendance accompanied

by Deputy Sheriff Squyers.

Attorney Eckley arose from a seat in the rear of the undertaking parlors and raising his right hand, and placing his left hand upon the coffin of the dead man,

said: "I charge the detectives and other hirelings with the death of this old man and over his remains, before God and man, I take a solemn oath that

my future course through life, until the grim messenger of death shall clasp me in its icy embrace,

will be to avenge the death of this old man."

The convicted boy did the same.

There was a scene and many persons attending the services rushed from the room.

Engley and Hodgson, both under arrest for subornation of perjury, followed the remains, the procession being headed by a band playing

"Near My God to Thee."

That night, Engley as if in pursuance of his vow, stood in a doorway in the entrance to his office, next door to the Antler saloon, it is alleged, and

attempted to assassinate John C. Fraser as he passed on the street.

His purpose was thwarted by a friend of the melodramatic lawyer.

Later he stood in the Antlers saloon leaning against the wall, his hand in his hip pocket, as the detective, standing sideways to keep an eye on the drink-crazed man, said,

"Engley, you are an old man; I respect your age; do nothing that you will be sorry for. Go on your way."

Later, friends of the attorney took a big pistol from him.

All of the cases of perjury were continued until the September term of court.

Andy Sellers, however, came to trial on the 12th of April.

He stated that he had furnished money to Engley with which to hire men to testify in behalf of the ore thieves, and that he was the one who had secured Killam and the others to testify.

It was upon this same date that Engley was brought to trial before Judge Cunningham.

He made charges against Judge Seeds, alleging conspiracy, ridiculous and unfounded of course.

Engley was acquitted of the charge against him on the 15th.

ON the 16th he was reported as being broken down.

He rushed into Judge Seeds' court while an argument was in progress and demanded that the judge "sit down."

He was overpowered and taken from the court room and confined in the county jail.

After the officers had relieved him of another big revolver, he fought like a manman.

His friends say that he was not responsible for his actions.

Kerch Kuykendall was called before Judge Seeds and given a sentence of fourteen years at hard labor at the Canon City penitentiary.

Harley J. Lake was given seven years and John B. Freidenstein, who had turned state's evidence, was sentence to a term of five to seven years, which was suspended.

Freidenstein was taken east by his father and is engaged in the peaceful occupation of a farmer in the vicinity of a small Pennsylvania town.

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen