The Real Mansfield as He Was Observed by a Post Staff Reporter Behind the Scenes at the Broadway

Mansfield, the crank.

Mansfield, the ogre.

Mansfield, the artist.

It is easy enough to describe Richard Mansfield under any one of these headings.

The newspapers are full of descriptions.

What The Post has endeavored to do is to describe the real Mansfield as he appears behind the scenes,

when actively engaged in rehearsing and presenting his plays.

WIth this end in view a reporter of The Post staff obtained a position as scene shifter at the Broadway theater and for three nights had opportunities of

observing the actor under the most trying circumstances.

His conclusion is that Mr. Mansfield is neither crank nor ogre, but is an artist whose whole mind is concentrated upon his work.

In his relations with his fellow actors he was firm, but considerate, and in giving instructions was never heard to raise his voice above the conversational level.

The real Mansfield behind the scenes is described by Mr. Bell in the accompanying article.

Mr. Davis writes and interview with him, and Mr. Phillips, who saw the manuscript of "Beaucaire" before it left the author's hands,

adds an interesting note.

"I hear you need some more stage hands and I need a job."

And the seedy, big-nosed, big-footed applicant assumed a look of desperation for much needed and immediate employment.

In the absence of Frank Bassett, stage manager of the Broadway and Tabor theaters, the petitioner was referred to Ellis Graham, stage carpenter.

A volly of questions were asked as to his capabilities, a satisfactor explanation as to need and willingness to work was made and employment was given out,

misgivings as to the ultimate result of the experiment, which was actuated by the good-heartedness of Mr. Graham in giving a fellow man a chance to earn a livelihood.

"Report here at 7:45 tonight and go on the stage floor and help set," brusquely ordered the man upon whom the important matters of properly setting the stage devolves.

It was on last Tuesday night and Richard Mansfield was portraying "Beaucaire."

The long-nosed, seedy-looking individual quietly slipped into the stage entrance and not without a feeling of the strangeness of his new employment.

Quiet pervaded, and the new hand was looked upon contemptuously by the forty-two men with whom he was to affiliate; there were little gestures directed at the tenderfoot in stageland,

but no outspoken disapprobation, nothing but whispers.

The first and important instructions given was no tacking must be indulged in, no noise, and the most perfect discipline was to be observed - or "Mr. Mansfield would be

put out and not like it at all."

And intimated that something disagreeable might happen.

You never happened to be a hired man, did you, on a stage where it takes a small army of men to make the numerless changes, and the go-and-fetch-in-a-hurry order of things?

Woes of the Novice.

"Where are you from?"

"You never worked with a show, did you?"

"Don't stand there!"

"Don't lean on that."

"Come over here!"

"Go over there."

"Keep quiet."

"Here comes Mr. Mansfield to inspect the first setting,

were a few of the questions and admonitions received by the writer, who was becoming a bit nervous and indisposed.

Mr. Mansfield in his makeup, from the conception of Beaucaire, minutely inspected every piece of scenery.

"Umph! Umph! Very good, very good, but - Mr. Graham," speaking to his stage manager, "this medalllion," pointing to a big run at one of the entrances, "is a little awry; please have it straightened."

Which was done by one of his stage hands, of which he carries eight.

These men have certain numbers of house employees told off to them, something after the manner of a squad of soldiers in charge of a corporal, and are divided in their work by these competent men.

To discover, if possible, Mr. Mansfield's disposition and manner toward an emplloyee, when interferred with, the new hand purposely ran into him, and with an assumption

of embarrassment, awkwardly side-stepped out of his way with: "Excuse me, Mister."

The Reply Courteous.

"Certainly, sir."

It was certainly a surprise, after hearing the numerous stories of how men were knocked down and subjected to other violences for like offenses from this man,

supposed to be always muscularly aggressive.

The great actor was human, considerately human, and under provocation, too, because he was not bumped into with any degree of gentleness.

The stage of the Broadway theater is a model of cleanliness, which applies to all parts of this vast place with its network of gear, and canopy of hanging canvas,

with the rows of border lights, which confuse the mind of the uninitiated.

Five minutes before the curtain rose the hands were distributed in places on opposite side from the dressing room entrance, and all had a point of vantage where the act could be seen.

The members of the company were assembled a few moments before the act was to go on.

There was no flurry, no noise; in fact, absolute quiet prevailed.

Mr. Mansfield looked over those in their places for this act, walked about with that keeness of knowledge of the every part to be enacted - was satisfied and then went off the stage as the scene flashed out upon the packed house.

The every line spoken and the every part played certainly showed that each and every one upon the stage was doing his or her utmost to protray the part as it has been

created and explained by Mr. Mansfield, the incomparable, to whom every character represented the living in the day, year and conditions on which this story had been founded.

This was the atmosphere prevailing, and easily observed, too, showing that the pupils were doing their level best to please their untiring teacher and to gain a word of praise, or perhaps censure as their case might warrant,

but in either event self-congratulation or any other criticism was received as it was intended: that is, for the furtherance of perfectness, and there was nop resentment or feeling

of injustice manifest among the players when sharply reprimanded by Mr. Mansifield because he does know what each and every representative should do.

The curtain came down on this first act.

"Here, me mye," spoke my boss, with a faint bit of brogue and in a kindly tone, for the news of my forlorness had gone broadcast.

"Take the side of this room - that's it, slide and carry it along - carefully.

There, now you did that first rate; place it here so it will be in regular order and not get mixed up with this second set."

And I placed my end of a 20x18 side of a room against the side of the building.

The Realism of the Stage.

"Now we will have to hustle," said my foreman.

"Get the furniture out of the store room; take that canvass off and be careful that you do not scratch the chairs."

At once a dozen of us uncovered a magnificent set of heavy carved gilt furniture - and how many people in the crowded theater knew that it was real and costly?

It was of the heaviest and most expensive kind and richly upholstered.

The tables and sideboard were of the most beautiful mahogany imaginable.

Each piece was carefully dusted, then wiped with a cloth, and the silver service, a collection of costly antique, carefully rubbed and put in order.

The writer was in a violent perspiration, such as one breaks into after doing a four blocks pavement race for a car, and very unhappy, too.

Putting down a medallion, which is stage parlance for the big floor mats and rugs, one side was a bit rumpled - more perspire, because the new hand had to square it up.

Everything has to be exactly in accord, or the men of Mr. Mansfield's staff would suffer the humiliation of having to do the set all over in order to have it harmonize,

according to minute instructions and orders of their employer, who views every set before the curtain is allowed to go up.

Another thing this big stager found in his going about among the ladies, was that each and every gown was of expensive

material of either silk or satin, and the workmanship of the best.

They fit with model likeness.

The costumes of the men were of silk, satin and velvet - well, the outfits for the production of "Beaucaire" must certainly have cost a small fortune.

There was none of the tinsel and cheap effects to be found, everything was immaculately proper, and, as has been intimated, the concensus of effort was to please Mr. Mansfield.

Sympathy for the new hand aroused the sentiment of "do unto others" among the boys in shirt sleeves who made the picture frames for the players, and he

was ushered into the first entrance by the limelight man so he could witness the performance.

Not that he was particularly interested in any plot connected with the piece being produced, because he was already weary and was tired of his job and was willing to lie down and rest,

and if it had been anyone but the magnetic, hypnotic wizard of character production he would have taken a sneak and gone down to Tortoni's for lunch.

But he, the new hand, was spellbound.

Little gestures with words of approval were given the desrving by Mr. Mansfield after this act.

Further Prospects of Labor.

Three more acts to pack off and tote on! Gee!

"In the morning," cheerfully volunteered one of my business associates, "we will handle all the heavy stuff that goes on in 'Baron Chevrial,'"

The new hand must have appeared delighted with the prospect of heavy lifting, long hours and steady employment to have caused the following:

"You're not going to quit, are you?"

I just longed for our country editor then to come and relieve me, for the third act was about to come on.

He is a big strong fellow, you know, and would do right well as a stage hand - and the writer is not of very robust constitution and

ill adapted for this kind of hurried labor.

We cleared the big space occupied by the stage in a jiffy, but not without great nodules of perspiration dropping from our faces, marking the stage like big rain drops, for this was the big

garden scene with the Diana and potted plants, we, meaning ourself, helped to carry out in the garden.

The coach was dragged from its place where the baggage comes into the theater, backed over on the south side, the handsome pair of white horses were brought in and hitched up, the door of vehicle

opened and Lady Mary Carlisle helped in, the driver got up and the footman jumped into his seat, and this bit of

realism was awaiting the cut to drive across the stage.

"Now we will have to get a move on," said the new hand's side partner.

We packed off the 500 plants - by actual count there were twenty-five - but we, meaning ourself, could not get up the right steam for enthusiasm in this work of making new houses, gardens, rippling

brooks and fountains and all that.

The business was too novel, or perhaps it was overwork.

Gentlemanly Rebuke.

At the end of each act Mr. Mansfield was uniformly kind.

If he spoke sharply to one of the players it was not done in a cutting, mean way, just a matter of business, and a pleasant injunction

followed each circumstance, all of which was done in the manner of a teacher coaching a pupil and impressing a remembrance of

the point admonished upon.

In changing the scenes there was no noise, no loud talking; just a quick, quiet execution of perfectly planned systematic order of things.

Acts three, four and five were taken off and put on without a hitch, and our work

pleased the eminent actor inasmuch that there was not even a look or suggestion from him to make any changes.

We, meaning ourself, hiking out good and fast just as soon as the big curtain fell on the last act, with a feeling of deep respect for every man, woman and child

connected with this company and stage work.

"Miss Irving," sharply called Mr. Mansfield as the leading lady was about through the passageway from the stage leading to her dressing room.

There was a smile on Mr. Mansfield's face as he joined the petite actress at the door.

Leaning with her head resting upon her outstretched, elevated arm, a la Juliette, she listened to words of mild cricism from Mr. Mansfield.

The gestures of the great actor betokened nothing that would indicate anything but a lesson, such as he had given to other members of the company.

The conversation was carried on in a low tone and but few words could be detected four feet away, where stood the new hand.

"Yes, Mr. Mansfield," and "No, Mr.s Mansfield," was all that could be heard.

For ten minutes they chatted, and then each with a pleasant "Good night" went their several ways.

"Oh, yes, the new hand slept without being rocked to sleep.

*****************

"Why didn't you show up to help in with the big heavy stuff this morning?" was the reception of the new hand when he presented himself to Mr. Graham Wednesday night.

"Well, it was like this: I heard of a steady job on a newspaper down town and hung around all day to see the boss, but he didn't turn up."

The explanation was accepted.

"I filled your place with another hand but I'll put you to work up in the borders.

After poking around a big banquet table, already prepared to be taken on in act four, the new hand was shown up a series of winding stairs to a place

where the trees, skies, ceilings and cloud effects are operated.

"Billy" is the boss in this net work of six-four pairs of ropes, thirty-five feet above the stage, where this rigging is made fast to belaying

pins in a piece of lumber running across the stage some four feet from the wall.

There is a six-foot floor running from end to end, and back of the rope-gear are a series of forty-one wire cables filled with weights to regulate the

staple borders and lights.

This system is unlike anything of this character in the country and is the work and ingenuity of Frank Bassett, the best known stage manager in the country,

who has had charge of the Tabor and Broadway for some dozen years, and is known to every professional person in this broad land as the best man in his line of business -

besides he is a prince of good fellows.

The Dictation of "Billy."

"Billy is the house man up here and the way he handles and orders this big tangled mass of lines and wires is a caution, he is here, there and everywhere and

the one man helper from the Mansfield staff watched him with outspoken admiration.

"You won't have much to do here tonight, Spaulding," he said in answer to a query if there would be much hard work - for this theatrical work was not to the liking of the new hand and was

a matter to be carefully weighed before starting in.

The lesson of the preceding night had left its mark in sore elbows and shins, not to mention that tired feeling superinduced by the unusual activity of a stage employer.

There was but little work required, and "Billy" set a chair for the pilgrim up in the clouds and explained the intricacies of his profession to this new hand

in a concise and easily understood manner, to any one with an appreciation or liking for his calling.

His adeptness appealed to the writer, that is all.

"Say, this show is put on in the real-thing way," he said.

I've never seen an outfit go in for such realness.

That is a regular banquet and the goods are there, the real thing."

A Feast for the Gods.

The new hand went down and sampled everything on that festival board.

There was three salads, olives, salted almonds, bread and assorted cake, cheese straws and many other good things.

The new hand was hungry and would have gotten a good square meal if the stage carpenter, Ellis Graham, had not happened along and

told him to get up above - quick.

The champaigne was the real thing, too, and when the table was taken off after the marvelous depiction of the old baron at the festal board,

the stage hands feasted and drank the good wine.

The cut flowers and smilax decoration of the table was expensive; the wine glass broken by Mr. Mansfield cost $1.50.

In all this one act alone cost many dollars.

Mr. Mansfield inspected each stage setting with the same careful survey as on the night before and coached and suggested in the same manner.

The new hand does not want any more employment on the stage, he has had enough to last him for all time.

"Oh, yes.

Those lime lights," explained Mr. Graham, the stage carpenter, "are not furnished by the house.

THey are too expensive.

They cost $2.50 a night apiece and Mr. Mansfield carries over 100 gas tanks to supply the gas for them.

No, Mr. Mansfield is not a crank, he furnishes anything and everything and when he does kick he has good reasons.

We all like him."

Inquiries among the stage hands prove that Mr. Mansfield is a fair and just man and well liked by them all.

The members of the company are enthusiastic in their kindly opinion of this greatest of actors.

Mr. Mansfield is so engrossed with his work that his mind claims no other thought than the play in hand.

It is not irrelevant to observe that the eccentricities laid at the door of Mr. Mansfield are not such, but his

outbursts came from a source heretofore left unsaid - and would it not be reasonable to say that they are caused by an idea of character that he has builded by

hard study, dashed to the ground by the introduction of this same ideal being misrepresented.

Liken this to a finished musician who shudders at a false note or bad technique, and I think that Mr. Mansfield's "eccentricities" are explained.

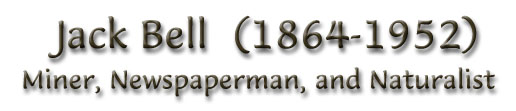

JACK BELL.

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen