How "Dad Rose's Long, Hard Life Faded Away In the Midst of the Dreariness of an Artic Night

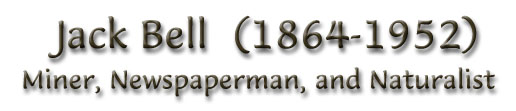

(BY JACK BELL)

"Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep,

If I should die -" Mother -

The old home - A-h-h-h."

The wind was howling like the [x] tails of hell; it was dark with the desolate darkness of an Alaskan night and not a sound could be heard but the whistling gale,

with an occasional yelp of a Siwash or MacKensie river huskie, as they cried for admittance into some miner's tent or dugout.

The night was the very worst that had come upon us in the winter of 1900.

I had just come from down the Ophir river a few miles, where I had cut some frozen willows to bake out for firewood.

The description that always accompanies the story of how thoughts flash through the brains of a drowning man is a mild comparison to the ever present feeling that

one has up in this God-forsaken country that is as utterly apart from anything human as can be imagined.

I am speaking of the Ophir country in the interior Nome waste.

To get up there one must take a slow sailing craft from Nome and go down the coast to Golovin bay; then up the Neukluk river to Council City and then

"mush" over the big range of hills - a short cut of sixteen miles - to the camps on Crooked creek, the richest diggings on the peninsula.

High spurs of hills break in every direction, with sugar loaves cut out here and there by little valleys and draws.

All destitute of timber of any description - nothing but a few bunches of low, water soaked red willows, that are the only fuel obtainable.

I could write volumes on the heart-breaking conditions of this awful country, where hardy men go, with rich placer diggings as the incentive for risking their lives.

There were about twenty of us wintered up there in the blackness of each twenty-four hours of every night.

You must understand that there is no such thing as daylight or gleams of twilight in the Arctic circle zone from the middle of November until the middle of March.

Added to the morbid gloom are the soul-chilling blizzards that are incessant in their shrieking fury.

Talk about hellish parallels!

Go up there and put in one winter and partake of the hardships that are cheerfully endured by the Americans that have made the far Northern country famous -

by far the most famous - and yes, the richest placer mining country on earth. But I am getting away from the incident that I started to relate.

A Weather-Beaten Pioneer

Among the most beloved of all the old-time miners was "Dad" Rose.

He was a '49er, had been to every placer excitement in all parts of the world and was as rough and hardened as a burro mountain pack.

He carried his 70 some odd years as easily as we did our one and two score, and did his work of prospecting and sluicing uncomplainly.

He was a model that all tried to follow.

He was of a quiet unassuming manner, and all of the men in the diggings tried to be as cheerful and thoughtful as the old pioneer of placer mining.

He lived in a little bit of a dugout on the right bank of the river in the middle of his claim, No. 34, above, which he had located and made pay.

I brought his winter's grub over from Council with my dog team long before the first bad storm.

The old fellow was ailing, and by the middle of January he was unable to leave his home.

He refused our proffered aid and said that he had a slight cold and would soon be able to visit up the gulch.

On the evening that I was passing with an armful of brush I naturally turned in by "Dad's" camp to see if I could be of any use.

In a quavering voice of pathos that made the tears start from my eyes and freeze upon the hood of my parkee the poor lonely prospector was sobbing the prayer that had been

taught him at his mother's knee almost three-quarters of a century before.

Memories of my own early childhood surged through my mind and my throat ached with suppressed sobs, with the knowledge that I was so many thousands of miles from my people

that I loved so dearly, with no possible chance of communication for months, I realized the utter forlorness of the place where I was.

"Dad! Ho! Dad!" I called. There was no answer. I knocked again, and then again, calling louder each time, for the awful storm was knocking me about.

After repeated knocks and calls I burst in the door.

The Old Man Was Dead.

There was the old man kneeling by his bunk; his arms were outstretched across his blankets and the long silver-white hair and beard flowing about his head and shoulders.

He was dead. He had panned his last dirt and cut his last trench.

I gently placed him on his bed of willows and moss, lighted two more flickering candles, closed the door and staggered and

stumbled against the storm to the camps of the boys two miles up the winding gulch.

For two long hours I bucked the storm - a circumstance that is a nightmare to me now.

I broke into old Mike Welch's tent and dropped on the bunk, bushed.

"Boys, the patriarch is dead," I said between the big gulps of hot coffee that had been handed to me by one of the boys.

"Dead? The old man - 'Dad' Rose - dead?"

There was an oppressive silence for ten minutes.

The miners were affected and deep sighs were heard from the men huddled about the little sheet iron stove.

"It's a hell of a night for a man's soul to take flight," solemnly said Charlie Simpson.

"Isn't it awful to die way back here? Why, it seems that we are out of reach of the Good Man," ventured "Big" Dave MacCurdy.

We all sat in silence for some time.

"Boys, we will have to go down there and fix up the poor old fellow as best we can and give him the best we have," responded Bill Cotton.

We put on our parkees, fur mitts and mukluks and started down the gulch.

That return trip I will remember to my dying day.

At one of the upper camps a King Island dog sounded that indescriable requiem that is a peculiarity of the beast.

The fine snow cut what little of our faces that was exposed as we breasted the hurricane.

There seemed to be a smile of peace on the face of this remarkable old miner as the shadows of the waving candlelight fell across his grand old head.

"By G-, Jack! I can't touch him - and I want to do something to show that I am the right kind of a man," said "Skinny" Hinkley, an old friend of the dead man.

"But I can't, and that is all there is to it."

With a gentleness and a tenderness that is proverbial among all prospectors and miners the wasted body was placed in the best sealskin parkee

that was in the camp and the feet that had tramped the world over in search of gold were encased in the finest fur mukluks that was on the river.

As we started to leave, Big Dave MacCurdy turned, and with tears in his eyes and chest heaving, said:

Boys, he hain't any gloves on. I'll go up to camp and bring mine down. You see, his are a bit worn and mine are new."

Looking among the effects we found a Masonic receipt. This was the first we knew that the bearer was a member of the order.

"We might have known it, boys, by the perfect life he led," were the low-spoken words of Bill Cotton.

"We will bury him with the ritual tomorrow as the hour of noontime comes around."

We were a sad lot as we mushed back up the ice locked stream.

The two watchers banked up the stove with roasted willows and began their night's vigil with the dead.

Thawing Out a Grave.

Early the next morning we began thawing the ground for the grave.

In summer it was a pretty place.

Situated on the top of a sugar-loaf back of "Dad's" shack, one had a view of the whole country for miles in every direction.

This mound was a fitting burial place for our dead brother.

For ten hours we labored and the six-by-four last resting place of "Dad" Rose was ready to be occupied.

Then it was that Big Dave suggested evergreens.

"The nearest little pine tree is thirty miles away, 'way up on Gold Run, Dave, and it would be suicidal to take the trip," was the reply of the boys in chorus.

You can bet your -- life that 'Dad' will have the sprigs of green, if I go froze on the trial," half sobbed Skinny Hinkley.

And in less than ten minutes he was behind his dog team on his perilous journey for the Neukluk.

About 9 o'clock the following day Skinny aroused us all.

The poor devil had both feet frozen and one of his ears was big and black.

He had the prized bits of fir, and he was unmindful of his suffering.

"He will know that I took a d-n long chance for him, won't he, Jack?"

None of us could answer.

We were choked with the pathos of the scene.

It was the big-hearted fellow's expression of respect and love for the dead man.

The outfits came down from the upper camp and we were ready for the impressive ceremony of the Masonic burial service at noon.

The wind abated as, with careful steps, we carried the body, lashed in the heavy blankets.

The picture was weird and unheard of in its strangeness.

Even the howls of the dogs were silenced.

Gently, very gently, we carried the body to the icy grave on the high hill.

There was but one lantern on the river and it was mounted on a tent pole, carried at the head of the procession by Big Dave.

There were twenty of us in that line.

We gave the funeral service and the voices lifted in holy song echoed far down the quiet valley, for it was calm to sepulchur stillness.

"Earth to earth" was slowly and brokenly uttered by Bill Cotton.

We built fires over the frozen earth and lowered "Dad" to his final resting place.

It was beautiful in its impressiveness and the miners sobbed in the awful stillness as the wet dirt covered the body in that lonely,

far-away-from-human-habitation grave.

Not ten minutes elapsed after the headstone was planted until the storm reappeared in all its Arctic fury.

Providence?

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen