During my forty years as a tenured staff-member of the University of Auckland's English Department I taught a very wide range of courses (anything from Beowulf to Beckett and beyond), but my publications have mostly been on Shakespeare and his contemporaries and on New Zealand literature, with a sideline on nineteenth-century poetry.

During my forty years as a tenured staff-member of the University of Auckland's English Department I taught a very wide range of courses (anything from Beowulf to Beckett and beyond), but my publications have mostly been on Shakespeare and his contemporaries and on New Zealand literature, with a sideline on nineteenth-century poetry.

In Shakespeare's time playwrights often collaborated on the writing of scripts, and many plays were published anonymously or under the wrong name. So a lot of my research has been devoted to determining "who wrote what when". It used to be thought that Shakespeare, like God, performed his acts of creation alone. But over the last few decades it has become clear that, like others involved in the early modern entertainment industry, Shakespeare wrote several of his plays jointly with other dramatists. And it now seems probable that, early in his career, he contributed to at least two plays published without any author's name on the title page.

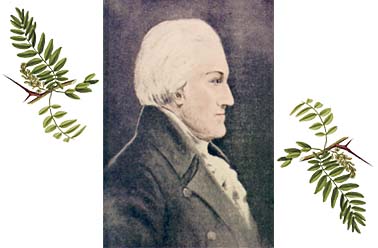

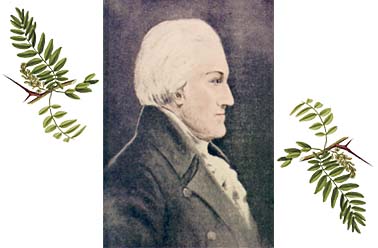

It was because of my interest in problems of authorship connected with Shakespeare and his great contemporary Thomas Middleton, in particular, that I read Don Foster's book Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (New York, 2000). I had met him and knew his work as a Shakespeare scholar. He gained deserved celebrity for discovering stylistic quirks and preferences that identified the author of the anonymously published political novel Primary Colors (1996) as Joe Klein. But he had also argued that the "W.S." who wrote a poem called "A Funeral Elegy" was William Shakespeare. I had disagreed with him over that attribution, but enjoyed his new book and found the chapter on "The Night Before Christmas" not only stylishly written but persuasive. It made a case for concluding that the true author of this poem, among the best-known ever written by an American, was not Clement Clarke Moore, as generally believed, but Henry Livingston. I soon discovered that Moore's champions had plenty to say in reply. But they seemed to me not to have satisfactorily answered Don's most telling points.

Here was the kind of literary whodunit that lures me into trying to be the Sherlock Holmes who solves it.

I checked out all the arguments on either side of the debate. I read Moore's Poems (1844) and the poems by

Livingston made available on Mary Van Deusen's splendid website. Livingston's poetic personality

immediately appealed. His moving "God Is Love" sums him up: he was full of love for

everything and everybody in the world around him. I admired his warmth, empathy, bonhomie, eye for detail, and good-hearted wit.

There was an endearing delicacy about the poems on the death of a young niece's pet wren (in the tradition of Catullus'

on the death of Lesbia's sparrow, a poem that he refers to in one of his own) and of the little dog Belle. He could enter

into a child's world. He relished the essential being of all living creatures. In one of his rebus puzzle-poems he refers

to the eighteenth-century novelist Lawrence Sterne, the author of Tristram Shandy, as

"The author of Shandy, all laughter and glee

Whose pencil from gall was forever kept free."

He himself was not ALL laughter and glee - his epitaphs and elegies are heartfelt, and his accounts of the

year's events in his New Year addresses are realistic - but as a poet he is remarkably free from "gall."

Nobody could say the same about Clement Moore's verse, which, in contrast, is that of a satirist and moralizer. And whereas Livingston's poems teem with detailed concrete references to individual persons, animals, birds, insects, and things, Moore's tend towards the abstract and generalized. Livingston's verse shows many signs of the lively, whimsical fancy, and the narrative skill that could create "The Night Before Christmas." Moore's, at least in Poems (1844), does not. Livingston knows how to shape a poem into "beginning, middle, and end", whereas Moore is inclined to just meander on. I could find no evidence in Moore's verse, even his manuscript pieces for his children, of the imaginative zest of "The Night Before Christmas."

However, it is not unknown for writers to surpass themselves and achieve an uncharacteristic one-off hit,

and questions of authorship cannot be settled by mere impressions. It is necessary to devise objective tests.

I contacted Mary, and she and Paul and their friend Lyn, with their exceptional IT expertise, provided a wealth of data to be explored and lots of clues to be pursued.

Every test, so far applied, associates "The Night Before Christmas" much more closely with Livingston's verse than with Moore's.

Writing up the results takes time, but when they are published I hope other attribution scholars will try their own different approaches to the issue. It will surprise me if all reliable kinds of testing do not reach the same conclusions.

Mac email

Mac's latest book is coming out from Oxford Press.

MacDonald Jackson in Wikipedia.

Statistical analysis used to examine 'Night Before Christmas' authorship